I’ll go out on a limb and speak for all of us sport illiterates by saying: even we care about the Olympics. It’s in a league of its own, the be all and end all of sports achievements and, interestingly, a lot of that has to do with time and nothing else. First, there is the incredible history that goes back to 776 BC – when the Ancient Olympics are widely accepted to have started – being held every four years at the sanctuary of Zeus in Olympia, Greece. Then, there is how that four-year thing about it still applies: placing a four-year void in between Olympic games ensures that a professional athlete’s career can accommodate only a limited number of opportunities. Miss a beat at the wrong time and you miss out on bringing four year’s of dedicated preparation to fruition. Last, but certainly not least, there is something specifically for us watch nerds about it too: the accurate recording of these decisive moments, a task that Omega has been trusted with since 1932.

I could go on and on, but this article is not titled “A Brief Look Into The History Of Olympics-Specific Clichés” – rather, it is supposed to be a watch nerd’s selective look into the history of timekeeping at the “Modern Olympics,” as they’re frequently called. The history of the Modern Games officially began in the Panathenaic Stadium in Athens in 1896, while we note the first Winter Olympics to have been held in 1924 in Chamonix. Probably one of the milestones in the history of Modern Olympics was when the 1956 Winter Olympics in Cortina d’Ampezzo, Italy, became the first Games to be broadcast on television internationally.

Omega has been the official timekeeper of the Olympic Games since 1932, which is extremely early on in its history if you consider the tough, low-key decades that followed the 1896 beginnings, and especially when noting that was some 24 years before the Olympics had its first chance of getting closer to the global audience. Before we get into details, may we share a recommended viewing: this 48-minute documentary from 2016 (that we just discovered…) on the history of Omega’s Olympic timekeeping.

The Early Years

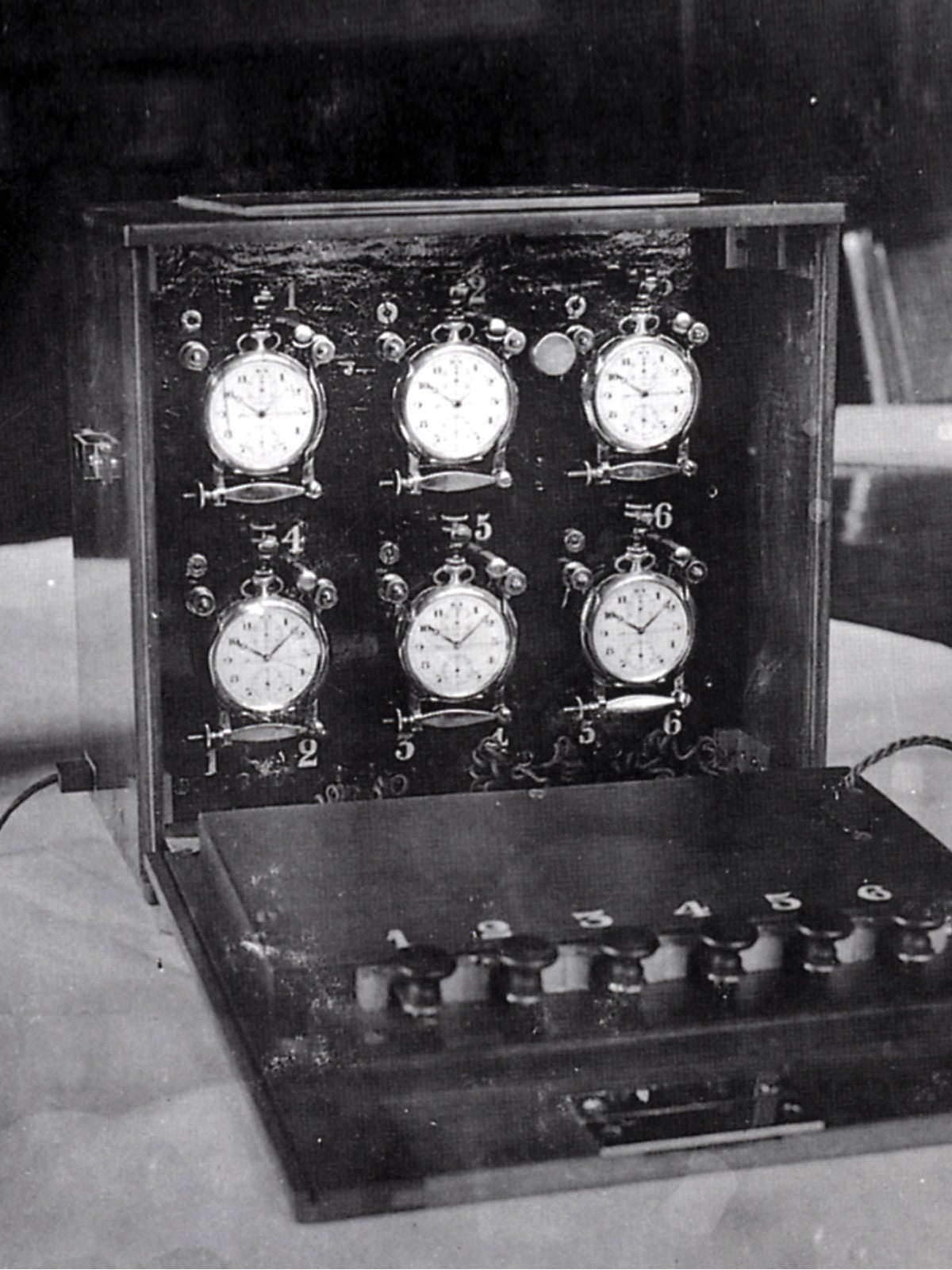

The 1932 Summer Olympic Games marked the first occasion in the history of Modern Olympics that the responsibility of Olympic timekeeping was assigned to a single company – Omega. Omega had provided 30 calibrated chronographs for “unprecedented precision.” Before this, multiple manufacturers provided watches that were only accurate to 1/5th of a second – causing such inconsistencies that times only for the winners were provided. By contrast, Omega’s 30 pocket watches were chronometers certified by the Neuchâtel Observatory and were accurate to the nearest 1/10th of a second while also featuring a rattrapante, i.e. split-seconds functionality.

It goes without saying, that at this point – and for another 16 years to come – the timing at the Olympics had been performed by human judges, not electronic devices, although a very basic type of photo finish had been used in the Olympics since as early as 1912. To average out bias and human error, each athlete in every sport where timing was crucial was timed by up to six judges – they all would have their own high-precision Omega pocket watch and the times they individually measured were noted, added up, and averaged out.

An original 1930s Omega split-seconds chronograph pocket watch used at the Olympics – seen at the Omega Museum in Bienne.

Another important, shall we say revolutionary development of the 1932 Summer Olympics was the “Chronocinema.” The Chronocinema was an experimental camera that could record times to the nearest 1/100th of a second for any exceptional timekeeping circumstances. Why those only? Because developing its film and examining the results took several hours and seven judges – I feel like I have a knot tied from my internals just imagining that agonizing wait the athletes had to endure… I mean, compare that to the instantaneously available, extremely detailed timing and footage of today – although later we’ll look at how top-tier athletes can produce controversial finishes even with modern technology watching over them.

As luck would have it, on this very first occasion of a singular timekeeper taking over all timing duties, there had already been a controversial finish in the 100 meters final between Thomas Tolan and Ralph Metcalfe (Omega’s documentary calls him Eddie Metcalfe, confusing Thomas’ nickname ‘Eddie’ with Metcalfe). It was here that the timing gave a different result than what could be visually observed. Timing on the Omega stopwatches for both indicated 10.3 seconds and it was Metcalfe who had been considered to have crossed the finish line first. However, when examining the Chronocinema footage, it turned out that it was Tolan whose torso first completely crossed the finish line and so he was declared to have been the winner by 5/100th of a second. We won’t go into further details but will just say that a year later, the International Olympic Committee (IOC) ended up changing the crucially important rules of how the winner of a running race is identified – and that rule has remained largely unchanged since then.

The Omega Magic Eye of 1948 was the first to rely on photoelectric cells like this to accurately capture a race’s finish.

The 1948 St. Moritz Winter Olympics and the 1948 Summer Olympics, also know as the “Austerity Games” of London have proven to be a turning point in Olympic timekeeping. Although London still bore the scars of the war and no new venues and Olympic housing were built, timekeeping – enjoying the technological advancements it underwent thanks to the arms race of World War II – had in fact taken notable leaps forward. St. Moritz saw Omega first use a photo-electrical timing system, later know as the “Magic Eye,” which in London was paired with the world’s first slit photo finish camera. Therefore, it was at the 1948 London Summer Olympic Games where technology truly began to replace humans in Olympic timekeeping.

The photo finish camera used in 1948 comprised a camera at the finish line linked to an electronic pistol that would start the race. The camera had a slit of a tenth of a millimeter in its frame, exactly aligned with the finish line where the winner obstructing a light ray would determine when the picture would be taken. The official announcement would come after two or so minutes – a considerable improvement over the Chronocinema of old. Interestingly, in 1948 the camera was only used to determine final rankings, not official results, but by Helsinki in 1952, the camera had been renamed the Omega Racend Timer.

Fun fact: Omega brought along 4 tons (9,000 pounds) of equipment to time the St. Moritz Winter Olympic Games… we aren’t sure whether that includes or excludes the Chevrolet – shown above, equipped with special shock absorbers – that the 5-man Omega timekeeping team used as their portable offices so that they could move between the many different stages of the event. On a personal note, this one of the Omega Olympic Timing car is probably my favorite image of them all.

Helsinki, 1952, had brought along yet another important advancement in timing technologies: the Omega Time Recorder. This amusing, vaguely named system featured an electronic, quartz-driven chronograph and a high-speed printing device which enabled Omega to time events and instantly print out results to the nearest 1/100th of a second. Although quartz-driven systems had been used before, the Omega Time Recorder was the first portable device that was also battery powered, hence allowing it to function independently from the often unreliable electricity systems of the era.

Fun fact: The 1952 Helsinki Games were the coldest ever Summer Games with an average temperature of 5.9°C (42.6°F).

Melbourne, 1956, brought along yet more innovations – only to lead to one of the most controversial finishes in the history of the Olympics in 1960. Let’s not get ahead of ourselves though and check out the great novelty of ’56: the Omega Swim Eight-O-Matic – joyfully named in line with product naming practices of the era – the world’s first semi-automatic swimming timer. The original timer featured eight electro-mechanical counters, one for each lane, and each with a digital display. The starting time was automatically triggered by the pistol, while the counters were manually stopped at the finishing line by the timekeepers with hand-held electric timers.

Not-so-fun fact: In the women’s 100 meter backstroke final, two competitors each clocked the winning time. Judith Grinham and Carin Cone both hit the wall in a dead-heat time of 1:12.9 – a world record. According to the rules, only one of them could receive gold and so it was on the judges to decide who had won. In the end, the majority decision gave Grinham the victory while Cone took silver – putting Cone in the unusual position of claiming a world record but not an overall victory.

The controversial finish between John Devitt of Australia (lane 3) and Lance Larson (lane 4), watched by the judges. Source: STAFF/AFP/Getty Images

Rome, 1960 saw one of the great controversial finishes in Olympic history. In swimming, the 100 meter freestyle final between Lance Larson and John Devitt saw a dead-heat finish. You see, each swimmer’s time was recorded by three timekeepers each, whose timing results were in Larson’s favor. There were also three first place and three second place judges who were split to decide who came first. Ultimately, the advice of the chief judge was followed, ruling that the time was to be ignored and Devitt was declared winner – once again, leaving Larson, the runner-up with a record fastest time, but a silver medal.