The Rolex Daytona 116520 has been with us for over 16 years, from its debut in 2000 until its replacement, the part-ceramic 116500 (hands-on here) debuted in 2016. The steel Daytona has not only been a rare bird that Rolex has often made extremely difficult to obtain, but also an icon among luxury chronographs. I had one around for a couple of weeks and, not too long after starting to wear it, I asked myself the question: is the steel Daytona a real watch lover’s watch? Has it aged well? Has it retained its magic, or has its fame made it let its guard down as competition became fiercer every year? Lots of questions on my mind, so I set off seeking answers.

A Brief, Non-Teary-Eyed Recap Of The History Of The Rolex Daytona

There’s a saying in Hungarian that, in direct translation, goes like “it’s coming out my elbow by now.” Although, come to think of it, I am not quite sure how this scientifically questionable saying caught on, the Daytona’s history at this point may very well be coming out your elbow too – you have heard it so many times.

If you have no friends and want to make sure it stays that way, try and meet new ones in hotel lobbies, or on the internet, mocking everything, all the time. Alternatively, just learn these numbers and use them often at public gatherings: 6239, 6240, 6262, 6269, 16520, 116520. There are more of these Daytona references, but these shall already suffice to keep decent and fun human beings from spending too much time around you, should you talk about these frequently. The emphasis is on not calling everything by its reference all the time like a total douche – and not on being ignorant about watch history.

Although Rolex has been producing chronographs since at least the thirties, the Daytona’s history can actually be traced back to the fifties, when Rolex made a few chronographs which they at times rather unimaginatively titled “Chronograph.” The five lines of boasting on watch dials was but a mere dream at that point. Rolex appears to not really want you to know much about these ousted models – not one pre-Daytona chronograph is in their otherwise really quite detailed history page, nor is one in their yet more detailed history page on their press-only site.

Rolex Monoblocco Oyster Chronograph Antimagnetic Ref. 3525: a medical chronograph in stainless steel from around 1941. Source: Antiquorum

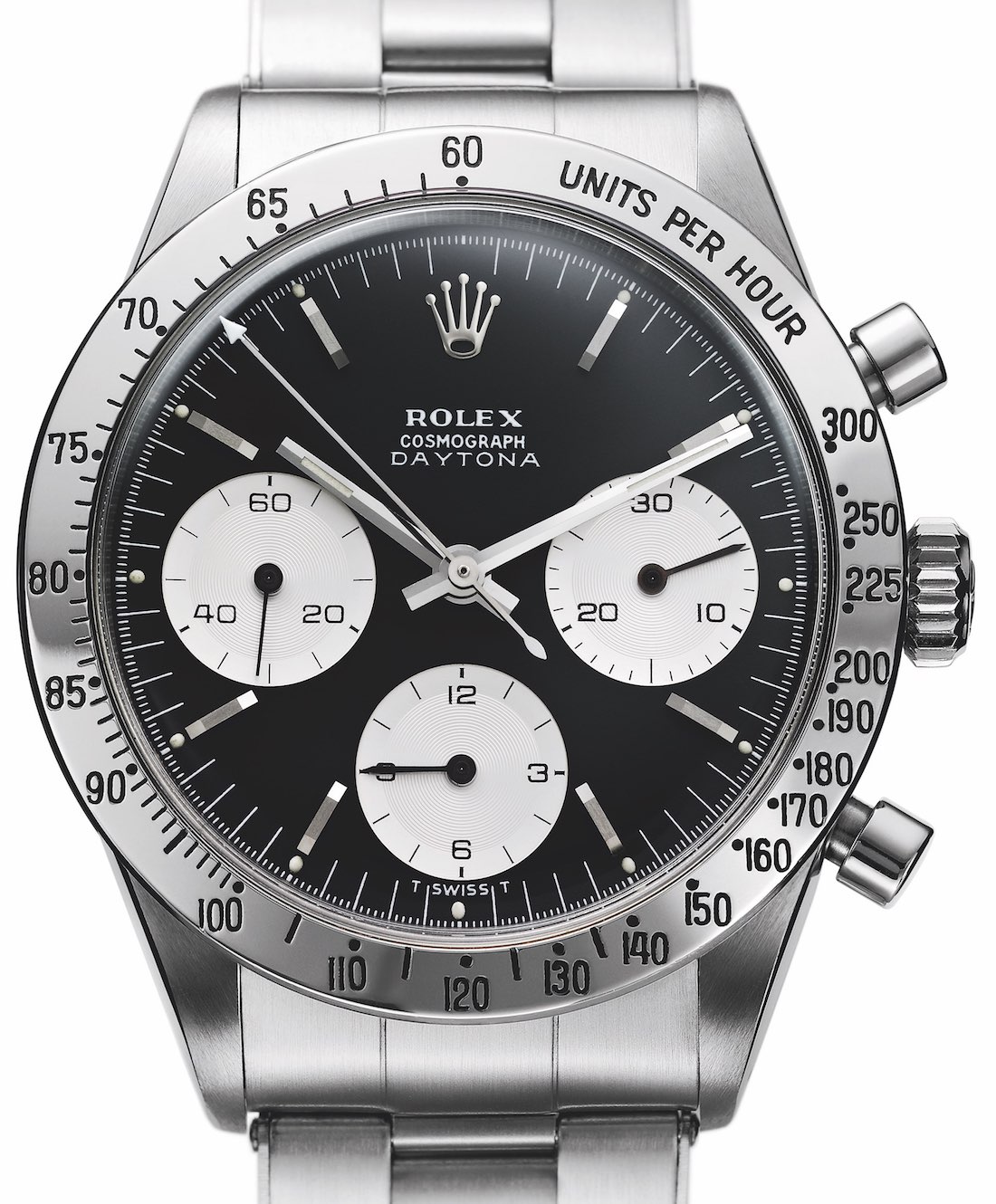

In a nutshell, the so-called “pre-Daytona” history that you may want to know is the fact that the Cosmograph name Rolex registered as early as 1955, and that the reference 6238, introduced in 1961 (some sources say 1963), was a solid-looking Cosmograph that didn’t yet have the Daytona name added to it. What Rolex does want you to know is the Rolex Cosmograph Daytona reference 6239 from 1963, the first “proper Daytona.” It was nicknamed “Daytona” after Rolex’s association with the Daytona International Speedway began in 1962. Still, to date, the full name of the Daytona is Rolex Oyster Perpetual Cosmograph Daytona.

Let us leap into the future, leaving the rest of Rolex Daytona history – filled with weird, fascinating and rare references – to you to research, and get straight to the Rolex Daytona reference 16520. Notice the 5-digit reference as opposed to the modern variants’ 6-digit number. Introduced in 1988 and in production until 2000, the 16520 is often referred to as the “Zenith Daytona” as it was equipped with the Rolex 4030 caliber, a movement based on the Zenith El Primero that Rolex modified mainly by fitting a different escape wheel and hairspring, and by dropping its operating frequency from the El Primero’s famed 5Hz to 4Hz. Before 1988, Rolex Cosmograph Daytonas used hand-wound, Valjoux-based calibers.

2000 saw the debut of the Rolex Daytona 116520 and with it the famed Rolex 4130 caliber that is, of course, beating inside this review unit as well as the latest, 2016-generation of the Daytona. The dials and the bracelet have also been changed around 2000, but this is not a comparison between these earlier models, so let’s concentrate on this review’s 16-year-standing “Steel Daytona” – as is called in hush whispers among watch enthusiasts who have been familiarized with the stupendously long waiting lists and stratospheric, albeit reportedly self-inflicted exclusivity of it.

First – and quite bad-ass – Rolex Cosmograph Daytona equipped with the 4130 movement, 2000. Source: Rolex

About Why The Steel Daytona Has Been So Difficult To Get

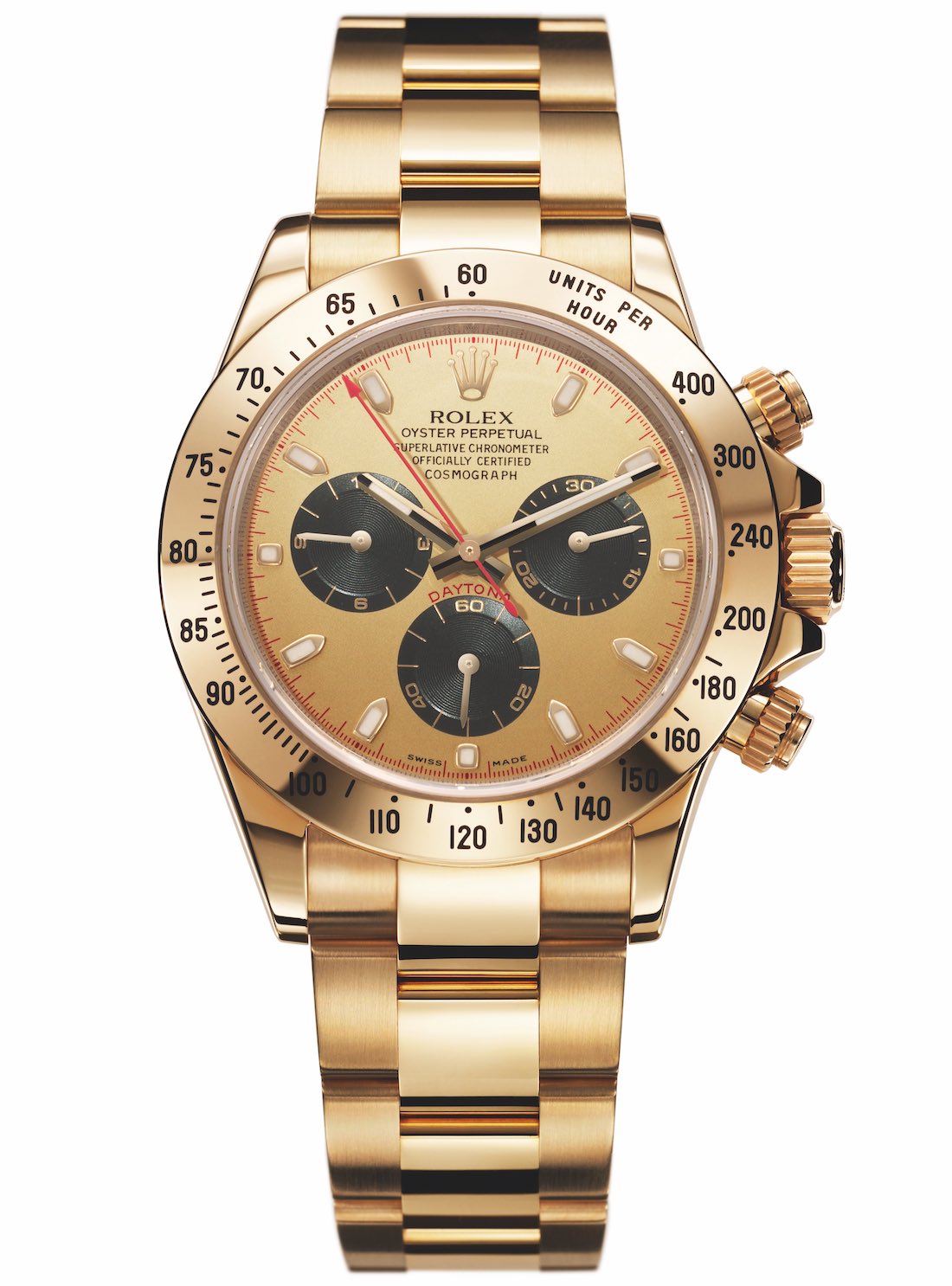

I mean, I dare not think how many articles, forum posts, Q&A’s I have read and discussions I have had about the Rolex Daytona, and a lot of them at least touched upon this remarkable exclusivity of the steel Daytona. If you had the gold one it just meant you had more money to spend on it, but in watch enthusiast circles rocking a steel one to this day means you likely dedicated a lot of effort in hunting one of these down – if it were to come from authorized sources, that is.

One thing I hand on heart do not recall reading or hearing is what could very well be the real reason for the limited availability of the steel Daytona: its movement (and, since its 2016 update, which we’ll look at in a separate review, the ceramic bezel), that is very costly and difficult to produce. Time and again we see brands painstakingly develop complicated movements or other features which they will only make available in precious metal cased versions – even if other models of the same brand do come in steel. The reason behind this tactic is that the much higher mark-up on precious metal cases help cover the very high costs of both the development and the manufacturing of said new movements or features.

Just to find a most fitting example from Rolex’s recent past: the new “Pepsi” GMT-Master II (hands-on here) with its bi-color, massive-pain-in-the-neck-to-make ceramic bezel, that (some say, and I agree) to date comes exclusively in white gold because the bezel is just too difficult and costly to make in the price range and in the volume of steel GMTs. Based on what I learned about manufacturing colored ceramics, I’ll go so far as to say the source of the issue is in the pigments used to color it as pigments don’t take the heat required to produce ceramic quite well and often form faulty areas in the surface. The “Batman” or “BLNR” is a modern steel GMT that has a bi-color ceramic bezel, but with two easier-to-produce colors. Okay, we got super side-tracked here.

All this was to say that steel Daytona supplies have been consistently limited likely because it has a movement that was and perhaps still is very difficult and expensive to produce up to Rolex standards at steel Rolex price points – even if the Rolex Daytona 116520’s retail price has admittedly almost doubled between 2000 and 2015.

Some Food For Thought Concerning The Daytona’s Allure – And If It’ll Last

Cutting straight to the chase, the Rolex Daytona 116520 changes its looks like few other watches do: it can quickly (and without notice!) transform from being one of the most versatile, elegant and sporty watches to one of the most boring and sedative timekeepers. I wish I didn’t have to, but feel like I should, so I’ll say that design preferences and the effects of a watch’s aesthetic are down to personal preferences, so your experience may differ from mine – but I will say there’s a good chance that some time into wearing the steel Daytona you’ll come to a similar conclusion as mine.

The Daytona provides one unquestionably iconic aesthetic and beholding a piece of that can feel both rewarding and infirmative. Here’s my issue with it: most iconic designs that you see gazillions around you are only appreciated by die-hard fans and enthusiasts if said designs have fascinating details and numerous variables. Think of the 911, for example. It’s everywhere, but you can change its specification, not to mention various special editions, limited production runs, technological variations and other factors; so, while a considerable percentage of 911 drivers may be yahoos who know nothing about the car, true enthusiasts remain loyal because there are always details that they find fascinating.

This steel Rolex Daytona 116520, over its 16-years, I feel, has failed to offer a refreshing range of fascinating details – let alone offer many of them. Even tracking the serial numbers and production years have been killed off in 2011 with the introduction of soulless random serials. Rolex’s reasons to keep things this very consistent are to be discussed in a separate article – because this does happen for a few logical reasons – but their cumulative effect on the steel Daytona ownership experience are very much relevant here.