Breguet And A New Business Model: The Subscription Watch

Like any good businessman, Breguet wanted to keep his business expanding, but to do that, he had to make his products available to a (very slightly) wider audience. To do this, he had to make Breguet watches available at a lower price, and so he created a new type of watch that could be produced at lower costs: the so-called souscription montre or “subscription watch.”

The easiest way to tell apart a subscription Breguet watch from the rest is that it has only one hour hand and no minute hand, running over what most of the time is a more simple-looking enamel dial with a 5-minute track on its periphery. Breguet did not simply omit the minute hand but designed a completely new type of movement just for these subscription watches. Thoughtfully engineered to be more simple, the movement did away with the motion work required by the minute hand (every single gear, movement bridge, and plate that had to be manufactured in this era required incomparably more time and effort than they do today, hence making a much greater difference in cost and final price to the customer).

The more simple movement had the mainspring barrel in its center with a symmetrical going train wrapped around it, with the caliber more often than not being fitted into a larger case – small cases with complicated movements meant greater refinement and hence were in a different category altogether from subscription watches. The simple movement construction allowed for the watch to be repaired by any trained watchmaker and not exclusively those at Breguet, further reducing maintenance costs. The subscription watch in essence served as a great and hitherto largely unprecedented way of increasing production output (and hence sales) through a combination of simplifying manufacturing, lowering costs, and hence offering the product at more attainable prices (mind you, still the equivalent of a smaller home in Paris, probably).

Breguet Patents His Perpetual Calendar Mechanism

It was Pope Gregory XIII in 1582 who commissioned what we today know as the Gregorian calendar and consider the internationally accepted civil calendar to this day. I’ll leave a drop of cool information that I found out about here: when the new calendar was instituted by the papal bull Inter Gravissimas of February 24, 1582, the necessary correction was accepted that the day after Thursday, October 4, 1582, would be not Friday, October 5, but Friday, October 15, 1582. This new calendar duly replaced the Julian calendar that had been in use since 45 BC, and it has since come into near universal use.

As you can see, the Gregorian calendar got off to a strong start by adjusting by a whopping 11 days, but the following centuries, complete with months of varying length as well as leap years, meant that clock- and watchmakers had to find a solution if they wanted a timepiece that could follow the track of this challenging pattern.

In 1795, Breguet patented a perpetual calendar mechanism that would allow for the pocket watch to display the day of the week, the day of the month, as well as the name of the month. Perpetual calendar watches have become much more common since then, but they still remain a rather luxurious and highly complex mechanism when it comes to offerings by major Swiss brands. Here you’ll find all our articles about perpetual calendar watches.

It may be time for that (second?) cup of espresso, because the list of important innovations by Breguet is just so long… That said, there are two more technical innovations that are still very much present in today’s high-end watches and that we absolutely cannot ignore.

The Breguet Overcoil Balance Spring

First, and also dating back to 1795, is the Breguet balance spring, today commonly known (by watchnerds) as the Breguet overcoil. As you know, the balance spring is the small spring installed onto the balance wheel. This little spring is attached at its inner extremity to the axis of the balance and at its outer extremity to the cock and, through its elasticity, regulates the oscillations of the balance. The flat balance spring, invented by the Dutch mathematician Huygens in 1675, had established a degree of isochronism which still left something to be desired. The flat balance spring was made of copper or iron and had only a few coils. Though imperfect, it gave the balance what it needed to become as accurate as the pendulum of a clock.

In 1795, Abraham-Louis Breguet solved the shortcomings of the flat spring by raising its last, outermost coil over the plane of the otherwise flat spring, hence reducing its curvature and ensuring the concentric development of the balance spring.

With this “Breguet overcoil,” the balance spring became concentric in form, watches gained in precision, the balance staff eroded less quickly – and, for a moment, all was well in the world. Breguet also perfected a bimetallic compensation bar in order to cancel out the effects of changes in temperature on the balance spring, but not even this several-thousand-word writeup will allow us to get into the details of that. What matters more is that the Breguet balance spring was adopted by all the great watchmaking firms, many of whom continue to use it to this day for high precision pieces.

Breguet Patents The Constant Force Escapement

Moving on to yet another technical invention of Breguet that is still used today – although exclusively reserved for haute horlogerie watches with at least 5-figure price tags – is the constant force escapement. Breguet patented it in 1798 and… that is all we’ll say about it now since we have written so much about this complication here on aBlogtoWatch that we won’t explain it all over again – but you can read about it more detail here and here.

The First “Tact Watch,” Made For The Empress Of France

Back to smart business decisions meeting technical innovation, we look at the “Tact watch.” Breguet knew his clientele very well, and his endeavor to offer yet newer timepieces to them was reflected not only in high-tech solutions but also ones that helped create demand that had previously not existed. What made the tact or tactile watch unique is that it had a hand protruding from its front cover lid that would rotate together with the hour hand on the inside dial, while the case’s periphery was fitted with diamonds to act as hour indicators.

The way it functioned was simple: the resulting timepiece was one that could be “read” relatively accurately through touch (accurately enough for the norms of the time, that is, when meetings were never ever arranged with to-the-minute accuracy), making for a most discreet way of checking time, where the company of the wearer would not notice her checking the time as she discreetly touched the location of the hand and indices. The watch could be placed in a pocket or even worn around a necklace as a pendant – it looked every bit as beautiful as a piece of jewelry, so fondling it people would not know that it actually functioned as a watch that was secretly telling the time.

The first tact watch by Breguet, made for Josephine Bonaparte in 1800, presently on display at the Breguet Boutique’s Museum on Place Vendôme

The first ever tact watch was created by Breguet for Josephine Bonaparte, Empress of France, that came in an 18K gold case with a stunning guilloché, blue enamel lid, and diamond-set periphery to function as hour indices. It was sold by Christie’s in 2007 for a whopping sum of 1,505,000 CHF, and at the time of my visit was actually on display in the Breguet museum, located on the second floor of the Breguet boutique on Place Vendôme (more on that in a bit).

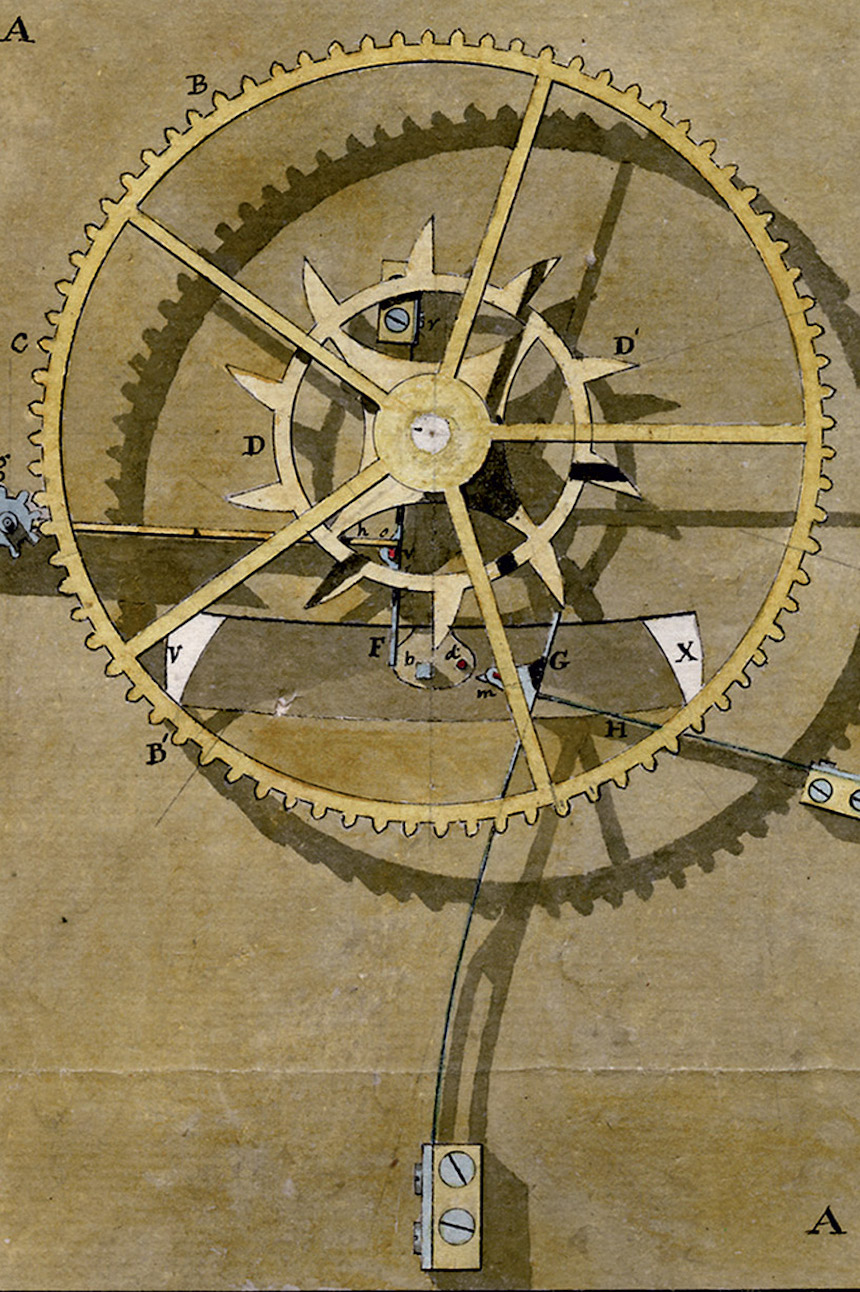

Breguet Invents The Tourbillon

1700s over, Breguet marked the new century in a grandiose way: by obtaining the patent for the tourbillon in 1801. Contrary to common belief, this is not the date when he invented the tourbillon – he started working on it as early as 1795. Interestingly, Breguet did not patent the majority of his inventions, for they took so long to develop and were so challenging to manufacture, that he did not have to worry about the (at most) handful of other watchmakers in Europe who could ever come close to copying his innovations.

Still, patent the tourbillon he did, on the 26th of June in 1801. The tourbillon will need no introduction to any serious (or beginner) watch enthusiast, but it is true that the Breguet brand has been serious about paying homage to this complication in their modern offerings – just check out the 5349 Double Tourbillon or the 5377 Extra Plat for some stellar examples.

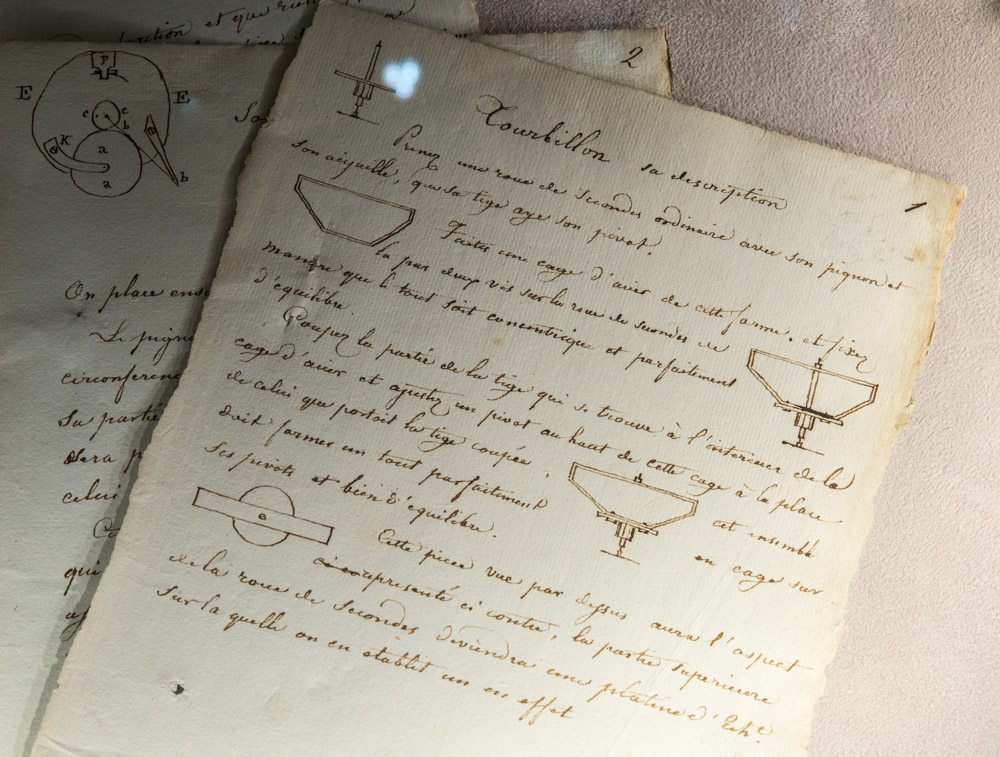

Breguets original hand-written notes on the Tourbillon – seen in the archives of the Breguet Boutique on Place Vendôme

So far, we have discussed Breguet balance springs, Breguet numerals, Breguet indices, Breguet’s tourbillon, automatic winding, perpetual calendar, and constant force escapement, as well as his “subscription” business model. Yet, his greatest contribution to the world is yet to come…

Caroline Bonaparte, the Queen of Naples, who ordered from Breguet the first wristwatch ever made. Today Breguet’s ladies watch collection is called Queen of Naples to mark this landmark in the history of horology.

The First Wristwatch Ever Made

According to Breguet’s hand-written archives, on June 8, 1810, the Queen of Naples – specifically, Caroline Bonaparte, a younger sister of Napoleon I of France – placed an order with Breguet for “a repeater watch for bracelet for which we shall charge 5,000 Francs.” Yes, a watch for bracelet means a wristwatch, the very first of its kind. To fulfill the Queen’s unusual order, Breguet imagined a timepiece of unprecedented construction and extraordinary refinement, namely an exceptionally thin, oval repeater watch with complications, mounted on a wristlet of hair and gold thread.

Sneak peak behind the safe door that guards some of the Breguet historical archives inside the Breguet flagship Boutique on Place Vendôme

Delivered as Breguet watch No. 2639 for a sum of 4,800 francs, the first wristwatch ever made according to any archive, possessed a lever escapement called a “free escapement” as well as a thermometer. To make it required 34 different operations involving 17 persons. In early December 1811, the watch seemed ready and was billed at 4,800 francs. However, according to Breguet archives, the system of the minutes had to be changed and the guilloché dial replaced – presumably at the Queen’s request – with a dial in guilloché-worked silver with Arabic numerals. The piece was finally completed on 21st December 1812.

Unfortunately, there are no sketches in the archives to indicate its exact exterior; what is known, though, is that the watch appears in 1849 in a register of repairs carried out on Breguet watches (technically, an after-sales service): dating March 8, 1849, Countess Rasponi, “residing in Paris at 63, Rue d’Anjou,” had sent watch number 2639 for repair. The repair, costing 80 francs, was recorded as such: “We have re-polished the pivots, reset the thermometer, restored the repeater to working order, restored the dial, inspected and cleaned every part of the watch and regulated it.”

The shape of the minute repeater movement follows the shape of the Queen of Naples women’s watch – a tribute to the first wristwatch ever created, made by Breguet as a minute repeater in 1812.

The first wrist watch makes one last appearance in Breguet documents when, in August 1855, Countess Rasponi brought her watch to Breguet to get new keys: one male key for winding, and one female key for setting the time. This mention is the very last trace that Breguet has of watch N° 2639.

According to the brand, “Today the watch is untraceable, and unknown to collectors and specialists. No sketch of the watch has been found in the archives. Nevertheless, we know that Abraham-Louis Breguet made the world’s first known wristwatch for the Queen of Naples. A piece with unique architecture and extreme refinement since it was a repeating watch with complications, oval, exceptionally fine, and worn with a wristlet of hair entwined with gold thread.” This is the story of the first wristwatch ever made – and it may have been lost forever throughout the countless tumultuous chapters of the last 160 years of history.

The Marie-Antoinette Pocket Watch

What better way of closing our time travel through the Abraham-Louis Breguet era than to look at the Marie-Antoinette pocket watch, arguably the most valuable timepiece ever made. It is the absolute pinnacle that stands as the perfect testament to Breguet’s genius as a watchmaker, to a craftsman who preceded his time by a century or two, and to his reputation as a highly successful businessman.

The Marie-Antoinette watch took 44 (that’s right, forty-four) years to make after it had been consigned by a “mysterious admirer” of the Queen to be the most complicated watch ever made at the time of its creation – and, as it expectedly turned out, for over a century more to come. According to Breguet, “the order, placed in 1783, stipulated that wherever possible gold should replace other metals and that auxiliary mechanisms, i.e. complications, should be as numerous and varied as possible. No time or financial limits were imposed.”

Breguet, unsurprisingly, dared to dream big – maybe a bit too big, in fact: the Marie-Antoinette watch was finished 34 years after the Queen’s death, and four years after Abraham-Louis Breguet’s death. The caliber comprised 823 parts, all of which were crafted with genuinely incredible attention to detail, and it allowed the watch to feature functions such as automatic winding, chiming mechanisms, full perpetual calendar, equation of time, jumping hours, seconds indication (a rare treat at the time), a bi-metallic thermometer, and an indication for the 48 hours of power reserve.

The Marie-Antoinette watch has an incredible story to it – yes, there’s even more to it than its simply fabulous origin and level of complication – and we even went hands-on with its original Breguet replica. Read Ariel’s hands-on with the Marie-Antoinette watch here.

The Breguet Manufacture After The Death Of Abraham-Louis Breguet

In 1823, Abraham-Louis Breguet, at the age of 76, passed away. It was the only son of the founder, Antoine-Louis Breguet who took over the company in 1824: having been immersed in watchmaking since his earliest childhood, Antoine-Louis pursued the work of his famous father. With that said, it was Antoine-Louis’ son, Louis-Clément, who breathed a new dynamism into Breguet, understanding that watchmaking from that point on had spread through all social classes. This led him to extend his activities by diversifying, particularly in telecommunications.

That “new dynamism,” though, led subsequent generations of Breguets to lose more and more interest in watchmaking in favor of other sectors like electricity or, later on, aviation – there is definitely some interesting stuff here that we’ll discuss in a separate article for lack of space here. These “distractions” were so serious that, in 1870, Louis-Clément ended up selling the watchmaking branch to the head of the workshop, Edward Brown. The Brown family, aware of the historical importance of Breguet and of the patrimony it represents, led the Breguet manufacture for the next century.

The sale to the Brown family happened a couple of months before the Franco-German war and the fall of the Second French Empire. This political instability had a direct effect on the Parisian business and the Breguet brand was disheartened to observe sales falling. We’d have to wait until 1900-1914 and the Belle Epoque to reverse this downturn and to see again an evolution of the demand. Breguet changed hands another time in 1970 to the Chaumet brothers, inheritors of the Parisian jewelry house. Then, in 1987, the Breguet name was bought by Investcorp, with a favorable context that allowed Breguet another evolution: for one, the production was moved to the Vallée de Joux in Switzerland; and second, there had been a substantial emergence of new markets in Asia and North America.