Talented and noteworthy independent watchmaker Andreas Strehler released one of his most ambitious timepieces to date; the highly-engineered Transaxle Remontoir Tourbillon. The small brand benefits from having a truly distinct looking case, which in my opinion is a big reason why the company’s watches are able to stand out. On the inside is a detailed and in-house mechanism which combines two important “grails” of traditional watchmaking. As the name of this Andreas Strehler product implies, it combines both a remontoire and a tourbillon. The point? Accuracy and consistent timing performance, of course.

Andreas Strehler refers to the system as both “transaxle” and “trans-axial,” which mean the same thing. The point of the movement is to “filter” the power emerging from the dual mainsprings in such a manner that is very consistent, which allows for great accuracy. Not only immediate accuracy, but accuracy over time as the power in the mainsprings change as the springs wind down. Watchmakers of old and today continue to battle for accuracy – even in a world where timing accuracy in mechanical devices has been vastly supplanted by electronic technology. Despite this latent fact, the pursuit of chronological excellence is one of the most admired and interesting areas of effort and development in today’s world of mechanical timepieces. Minds like Andreas Strehler pursue a variety of avenues on how to achieve a “very accurate watch.”

Andreas Strehler doesn’t actually make any accuracy claims for this product, which is unfortunately very common. An analog would be if a carmaker spoke in nuanced form about a new engine without ever actually discussing the car’s 0-60 speed time. My theory is that watchmakers (and this is actually changing at some of the bigger brands) are concerned about discussing performance because a well-performing watch can make lesser-performing watches look bad by comparison, and that’s because claims about accuracy may differ from unit to unit.

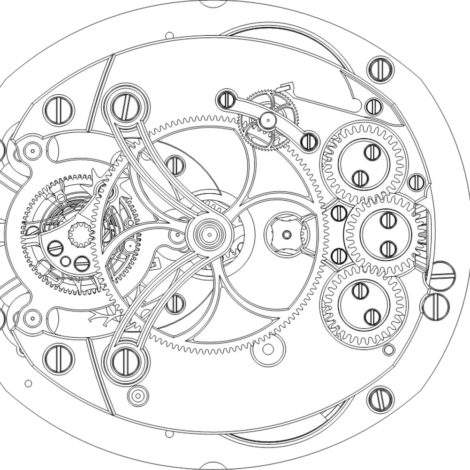

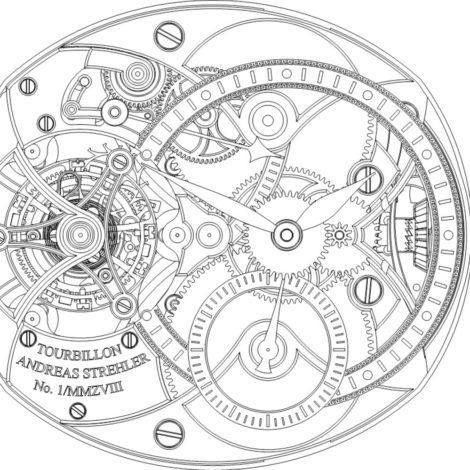

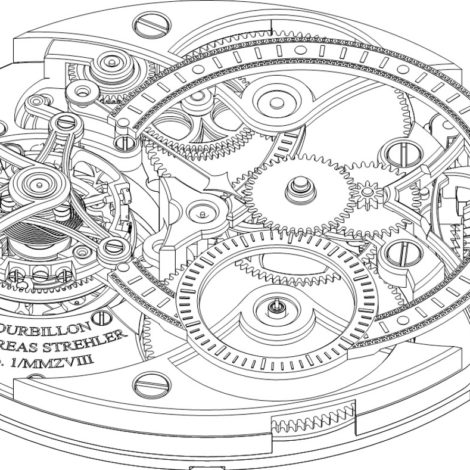

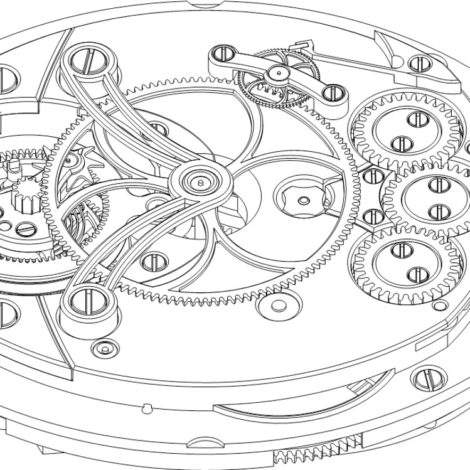

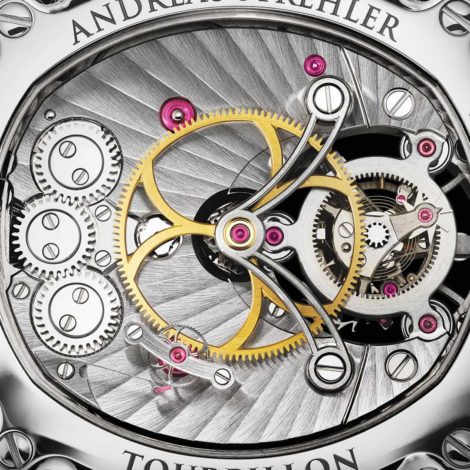

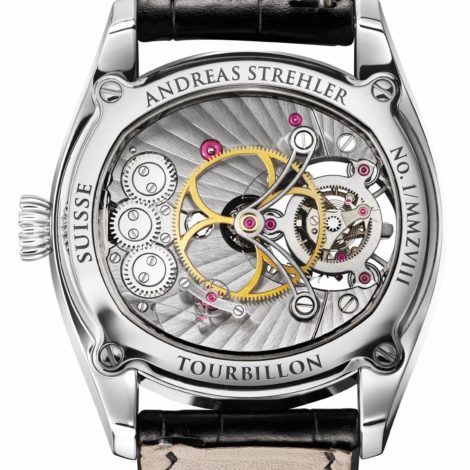

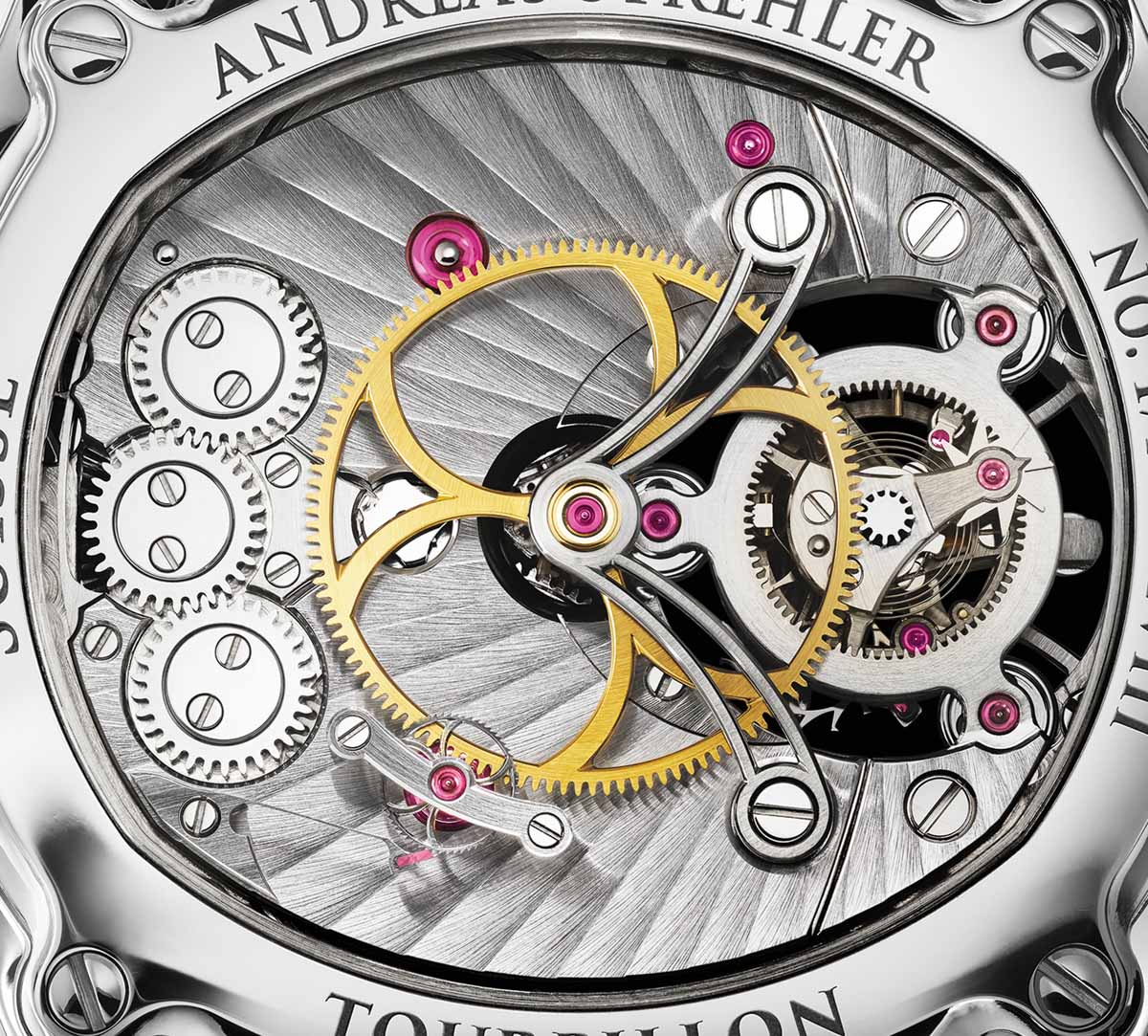

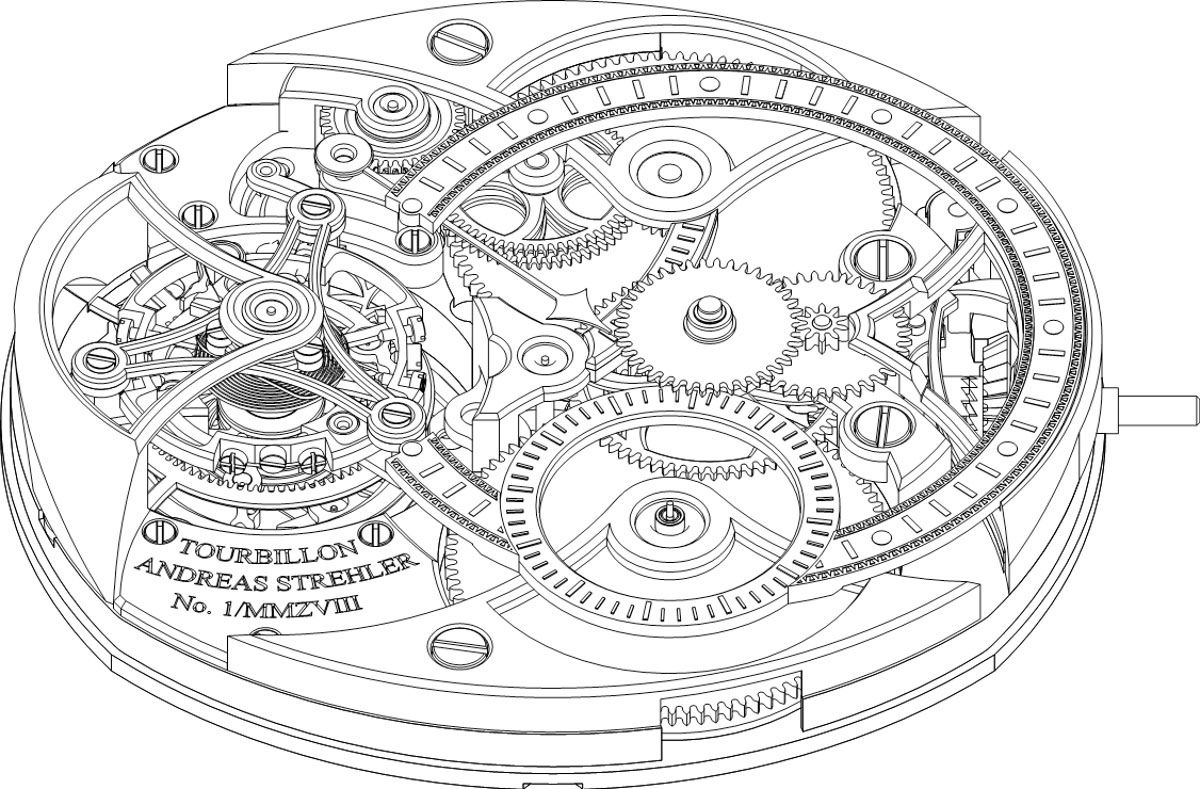

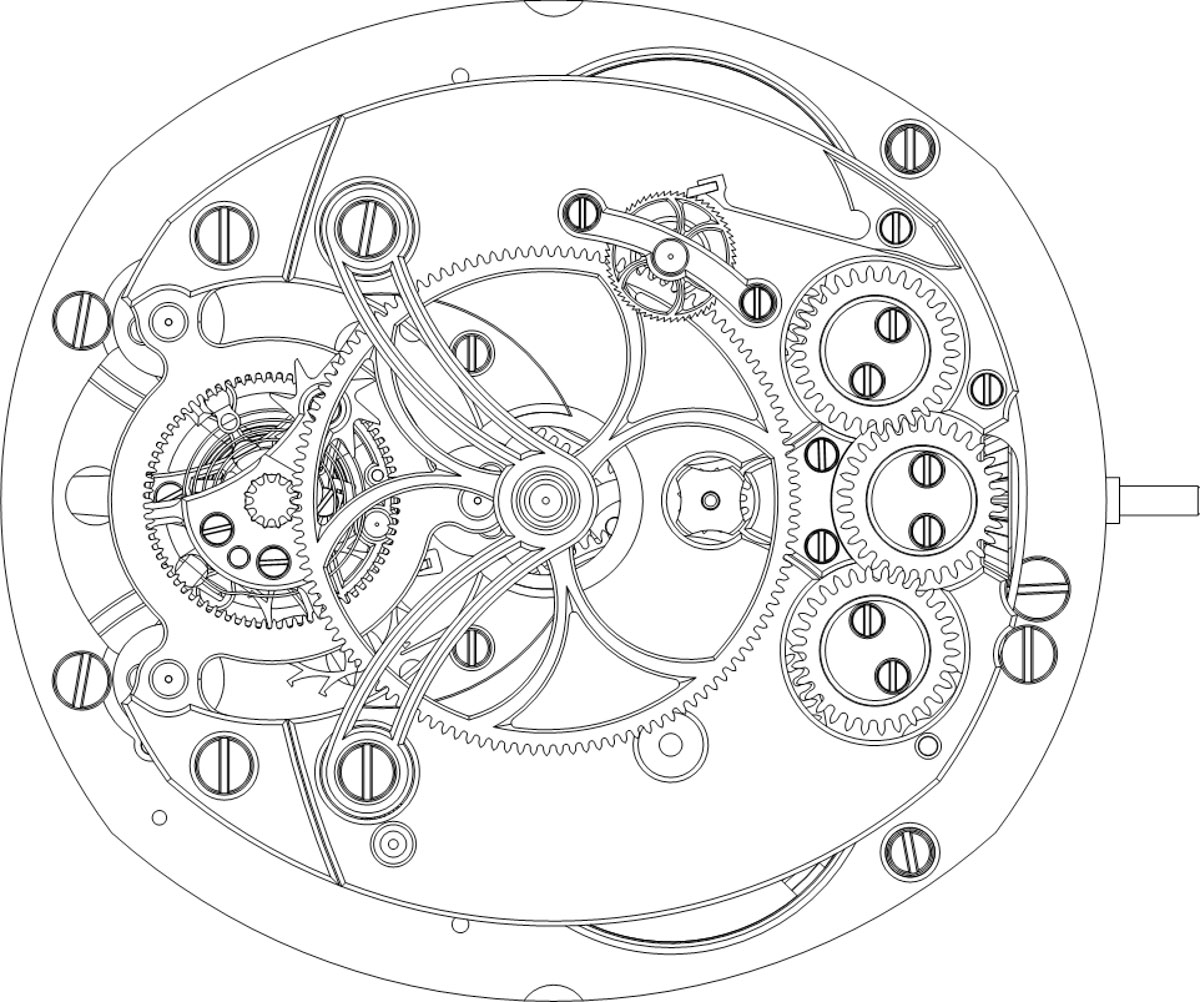

With all that said, let’s take a look at the epic level of effort included in the Andreas Strehler Tans-Axial Remontoir Tourbillon movement. There are horological nuances that are beyond the scope of an introductory article for this product, but I’ll hit on the basics. Again, to best understand the “point” of this mechanism, know that it both combines the traditional art of beautiful movement design and finishing, as well as performance in the form of a major effort to ensure consistent timing accuracy. The former can be determined simply by looking at the symmetrical elements in the bridges, the graceful, swoopy lines that make up the movement on both the front and rear of the movement, as well as the detailed polishing and finishing of all the parts.

The movement is produced from a very efficient 250 components, which is a testament to Andreas Strehler’s focus on efficiency. In mechanics it is the fewer parts needed to perform the largest number of tasks which is valued. Movements with lots of parts are certainly more complicated, but also more prone to failure and thus requiring service. Functionally the movement offers the time and power reserve, but all that needs a bit more explaining. An off-centered dial indicates the hours and minutes, while an overlapping subsidiary seconds indicator has a jumping seconds hand. This is an inherent element of most remontoire-based watches, meaning that the subsidiary seconds hand “ticks” versus sweeps. The 60-second tourbillon serves as a secondary indicator of the seconds and as most all tourbillons do, this one gracefully makes one full rotation each minute.

More difficult to notice is the power reserve indicator which is done via a long blued hand which starts just above the tourbillon and reaches a small scale under where the main time is displayed. Between two mainspring barrels the movement has a total of 78 hours of power reserve with an operational frequency of 3Hz (21,600 bph). Andreas Strehler artificially limits the power reserve to be a bit lower via a differential stop and an elliptical-shaped gear. Why? This is done so that when the power in the mainspring is too low to effectively power the operation of the remontoire (and thus accurately power the movement), it shuts down.

Constant force is really what a remontoire is all about. More completely, it is known as a “remontoire d’egalité.” The system is one of a few out there which is designed to produce consistent “pulses” to the gear train to ensure that the timing results are the same and thus the watch is accurate over time. Recent developments in parts produced from silicon have been some of the most interesting novel forms of constant force mechanisms as systems such as a remontoire d’égalité are at this point in history…. well, rather historic. Andreas Strehler is a purist, and a watch like the Transaxle Remontoir Tourbillon is clearly a product stalwartly dedicated to doing things “the old fashioned way” (but for today).

The star-shaped wheel visible on the rear of the movement is a key component in the remontoir complication. In essence, power from the mainspring powers a small spring that releases power only when it has a sufficient level of energy. This energy is designed to be very consistent, and this is in essence how a remontoire “filters” energy from the mainspring array to the rest of the movement. The tourbillon (in theory) is another system designed to protect accuracy because it is supposed to average out the rate loss in the regulation organ which can result from gravity. It doesn’t always work out that way in wristwatches (as opposed to pocket watches or stationary clocks), but there is value to it from an artistic and animation standpoint. No one who loves watches doesn’t love starring at a tourbillon in operation.

One of Andreas Strehler’s specialties is producing very small, very detailed gears – specifically, conical shaped ones (of which there are a few in the movement). This is most notably seen with the prominent conical gear in the crown stem which is part of the winding mechanism. It makes for a very efficient and reliable system to safely wind the movement.

The Andreas Strehler Transaxle Remontoir Tourbillon case can be produced in gold or platinum and is 41mm wide, 47.2mm from lug to lug, and about 10mm thick. The elegant semi-cushion case shape is classic, with soft lines which compliment the ornate detail of the exposed movement nicely. Attached to the case is an alligator strap. Price for the Andreas Strehler Transaxle Remontoir Tourbillon starts at 182,500 CHF. astrehler.ch