Tourbillons have come a long way during the past 200+ years of their existence. That time has proven sufficient to provide major ups and downs – and more than one full life cycle for this fairy invention.

Beyond those everyday complications which we take for granted, such as the date and the chronograph, I believe it is the tourbillon that remains for the beginner watch lover to get acquainted with. This statement should hold true even more so if considering the latter years of the new millennium, when it has become extremely difficult to find a brand which wouldn’t want to take the (continuously waning) advantage of the tourbillon in terms of distinguishing power.

Before discussing causes briefly, let’s quote Jerome Lambert, chief executive of Jaeger-LeCoultre: “A tourbillon is a must; if you’re a watchmaker now, you have to be able to master one complication and it has to be the tourbillon, because it is very visible”. In his words to the New York Times he also noted: “It is the most recognized and understood, and very appropriate to introduce in an emerging market.”

As a result of the soaring mechanical demand – mainly fired by Asia -, manufactures are doing what is necessary to provide ample supply. And just as Jerome Lambert remarked, it makes sense to emphasize tourbillons when doing so. However, the rise in output and the latter years’ transition into a selection more tourbillon-heavy than ever before, had its side-effects: a niche market evolved from the demanding enthusiasts who were looking for more than just another simple tourbillon model and this meant new challenges for the brands. Firstly, they had to come up with new and interesting ways to keep these aficionados interested by meeting their expectations for something new, and secondly, to compete with others in the consequent arms race. To do this, new approaches and some twists on the old tried and true recipe were necessary.

Beyond the effects of mere quantitative expansion, there was something else going on as well. I remember that after my first encounter and following some devoted research regarding single-axis “tourbies”, I had to face that on many occasions, the source of these wonderful calibers are not the manufactures themselves. In my view, such a realization should either discourage, or – if there’s enough fire left to remain zealous, then – motivate those previously interested to seek out other solutions, to find out if there’s more to that object of worship. If you are reading this, I believe I can say with confidence that you belong to the latter group of individuals and hence are about to delve into the details of one of the most spectacular and ingenious solutions ever found to spice up Breguet’s two-centuries old twist on timekeeping.

Growing into a family

It was not until January, 2002 that the first sketches were made of the Gyrotourbillon. Two stellar minds set themselves to tackling this mind-boggling challenge: Ms. Magali Metrailler was responsible for the aesthetic aspects of the timepiece, while Eric Coudray was to provide the technical background.

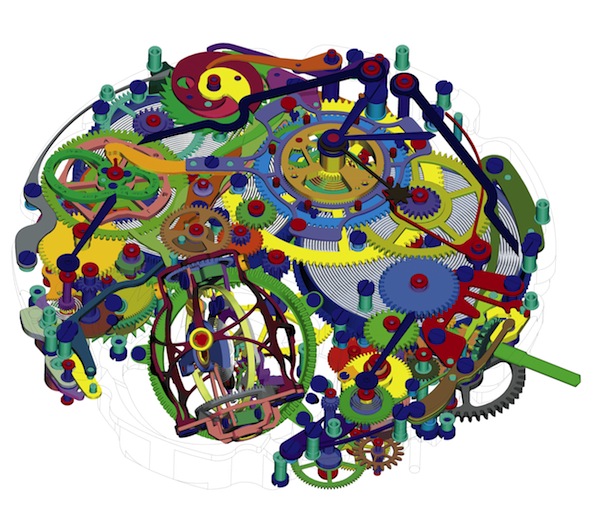

At the time of this writing in early 2013, we have the pleasure of gazing in wonder at three gyrotourbillon examples: on the picture above is the first, the Gyro-I in a Master-line round case. This piece is considered by many as a Grande Complication as it has an (inclined two-axis) tourbillon, an instantaneous double retrograde perpetual calendar, equation of time and power reserve indication. On a personal note, let me add that while there is no common agreement, it still usually takes one astronomical (calendar, equation of time), one chiming (minute repeater, sonnerie) and one timing (chronograph) complication for a true grande complication and this piece lacks some of those. This fact takes nothing away from Calibre 177’s power to impress, but is important to note.

The second model was the Gyro-II, housed in a 75-piece production run of platinum Reverso cases. The technical differences between this Calibre 174 and the earlier 177 are truly subtle yet telling, and hence worthy of further detailing. It must be noted that, as you probably have read about it here on aBlogtoWatch, the Gyro-III has been revealed in this year’s SIHH. Equipped with a Calibre 176 sporting a flying tourbillon and a chronograph – but on this occasion, let’s focus on the first two examples and see how JLC’s most turbulent decade will be even more interesting!

Inside the whirlwind

While tourbillons themselves are wonderful examples in the eyes of not only those craving better chronometrical results but those merely appreciating fine mechanics, some might find it abusive how many brands decided to take advantage of this beloved complication. With the power of classical tourbillons eroding, it was a safe bet to make that re-thought and re-purposed editions will be produced by manufactures eager to assure the public of their engineering prowess. That is exactly what Eric Coudray appears to have been born for. With the Gyrotourbillon movement, the intricate dance of the regular complication has been enhanced with success scarcely matched. The 90 degree inclination of the two axes truly doubles the fun, the three-dimensional movement of the cages opens up space and provides a seldom-matched opportunity for the spectator to admire this complication at work.

The spherical tourbillon, the centerpiece of every model in this micro-collection, is what we are here for so let’s divulge its closely held secrets! With it being double-axis, there are consequently two carrying platforms. To be more specific, one cage and one platform, the latter placed within the former. The external cage in all examples is made of aviation grade aluminum, a single-piece to be exact! The 3D machining of such a piece is extremely difficult to accomplish even with the latest CNC technology. The two-axis execution also inflicts two fixed gears around which the platforms can revolve. As it is known, a fixed gear is essential to provide a course on which the structure can revolve, and these being double-axis, a pair of such fixed wheels are necessary. Just below this paragraph are two pictures showing the fixed wheels highlighted in gold.

|

|

As hard to believe as it may seem, evolutionary development of even such ultra-products is possible. While there certainly are interesting aspects of such progress in haute gamme elements, witnessing what the new masters find lacking in their greatest achievements is always a real treat for the open-minded. The changes between the first and second models are mostly subtle, yet telling. The manufacture has not communicated its intentions of improving the second model’s chronometric results, however, the modifications applied to the second generation definitely suggest such purposes.

For starters, in the Gyrotourbillon I, the movement had also been equipped with a perpetual calendar and equation of time complications so the component count is much higher, 512 versus 371 pieces. The greatest difference from a buyer’s perspective, beyond losing the aforementioned complications, has to be the power reserve showing a major drop from eight days to a mere 50 hours. It is often noted that all tourbillons require a constant, even supply of energy from the mainspring to sufficiently drive the escapement. The tourbillon mechanism is of Babylonian proportions compared to normal escapements and hence requires much greater torque or else chronometric performance will suffer dearly. When it comes to communicating the Gyrotourbillon II’s power reserve, a so called torque limitation device is mentioned. Freshly patented by JLC and shown in the picture below, right on the barrel, this device stops the watch when there no longer is sufficient torque. This means that while having only one barrel, instead of two as on the first generation, the ‘reserve de marche’ could be higher than 50 hours, but beyond this limit, the watch would not run within acceptable rate requirements.

Another clue to the fact that the Maison intended to improve the chronometric performance is the higher frequency of the balance wheel. Instead of the earlier 21,600 vibrations per hour, it now beats at 28,800 vph, or 4Hz, further enhancing its isochronous properties.

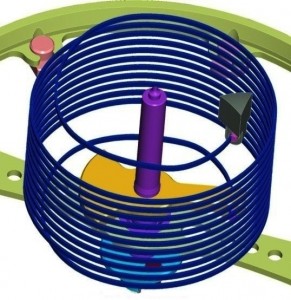

For the perceptive aficionado, the modified hairspring cannot be neglected from the list of developments. The previously flat spring has been replaced with a cylindrical one. A world first for wristwatches! Originally it was invented by John Arnold in 1782. The man duly remarked that he cannot foresee his invention being used in smaller timepieces as its spatial requirements are extensive. The modern age’s miniaturization techniques however have made this still amazing feat possible. The unfinished springs are supplied by Lange & Söhne Uhren – both companies being Richemont SA subsidiaries this is of no surprise – and then JLC’s watchmakers create the curve and through a week’s hard work, finely tune each and every example. As a consequence of added ‘useful’ weight, the moment of inertia had been increased from 10mg•cm2 to 12.5 mg•cm2, as a final effort for even better rate results.

A major question though remains unanswered. Beyond the war on numbers, axes and overall complexity, just what is so peculiar about these Gyrotourbillons that makes them so extraordinary? To understand this, before all else, one should closely study the photographs in this article. From anything as accessible as mere aesthetics to as subtle as the way the driving force travels into and within the cages, the chances to find something that moves one’s mind are more than generous. At a second stage, the visual stimulations proven to be sufficiently attractive, they have taken the time to rethink the entire the mechanism and improve the level of execution and the overall outcome. It had clearly been a tremendous undertaking merely to find the way the Gyrotourbillon could possibly work. And, at one whole other level, to finally make it through a limited, yet sustainable production run. The apparent ease of the movement at work and the sheer beauty that the complexity and lightweight components create are, to me at least, the main elements responsible for the striking and arresting nature of this terrific timepiece.

The time is now

There can be no doubt about the fact that a true manufacture will always live up to its name and with unceasing dedication and aspire to extend its previous boundaries. Just as it is seen here in this magnificent case of the Gyrotourbillon. For these select houses, no matter how wonderful, how mind-boggling their latest creation might have been, years cannot go past without a handful of masterminds working secretly somewhere, in a most detached atelier, on the next great chapter in mechanical timekeeping…

…And is there a better, more appropriate time for such mental ventures than now? For nearly two hundred years, Breguet’s idea of that mesmerizing dancing cage had been mostly unaltered (at least as far as the greater public was concerned), but now with the aid of the ever-expanding leaps in both manufacturing and communications technology, they can realize the daydreams of those aforementioned geniuses and reach the public in making their achievements available to a greater audience.

To my mind, there can be no doubt that for haute horlogerie (while arguably a niche market) there is at the moment, sufficient and solvent demand for both its clean, less sophisticated offerings as well as these ultra high-end realizations of scarcely paralleled achievements. With the detailed introduction of the Gyrotourbillon-III being just around the corner, those concerned may rest assured that Jaeger-LeCoultre, along with a few others in this game, will continue to strive for even finer, better (and for the more down-to-Earth spectators), crazier twists on this age-old recipe. I most certainly am looking forward to seeing what they come up with!