ETA & Ending Supply Of Movements To The Swiss Watch Industry

Above, I discussed some of the consumer psychology that explains why watches with in-house-made movements are in demand. Such a situation began in the 1980s as related to the modern luxury watch industry. In the early 2000s, something else happened which in many instances forced watch companies to produce in-house movements or face not being able to make watches anymore.

ETA is owned by the Swatch Group – whose founder Nicolas Hayek is often associated with the “saving” of the Swiss watch industry during the 1980s when many companies began to consolidate. One of Mr. Hayek’s acquisitions was the Swiss watch movement maker ETA. To a large degree, ETA had a legal monopoly in making high-quality, mass-produced Swiss Made movements which it sold to a variety of popular watch makers. The role of a “watch brand” for most of history was less as a factory and more as a creative director. The watch brand connected design with manufacturing as well as distribution and often marketing. The mentality of being a watch movement maker is and was often very different from the mindset needed to produce items for mass market consumption. The important role of the “watch brand” in recent history is to maintain the demand of mechanical watches in a post-mechanical-watch-as-state-of-the-art world by creating a luxury image around them.

The Swatch Group released a bombshell to the Swiss watch industry when, reportedly as early as the late ’90s, it began to announce plans to cease operations of ETA as a supplier of watch movements to third-party companies. This message was accompanied by delays, legal proceedings, interference from the Swiss government, and endless controversy. Ultimately, the Swatch Group was given the right to wean the industry off ETA movements and sell only to who they wanted, in whatever quantities they wanted. Again, the article linked to earlier on the history or ETA has a lot more information about this important series of events.

The Swatch Group claimed that it was lending the “Swiss Made” name to a lot of brands that it felt didn’t deserve it and that it was making it too easy to compete with its own brands that used ETA movements including Tissot, Hamilton, Longines, Certina, and more. The Swatch Group encouraged its competitors to invest in making their own watch movements as a means of answering their demand for producing mechanical watches.

At the time that this was going on, many people did not understand the Swatch Group’s goal in choosing to end supply to the larger Swiss watch industry. On the one hand, ETA had almost no competition, a vast monopoly, and plenty of steady business. On the other hand, ETA was producing movements that could have been going into Swatch Group brands, but were forced to be sold to outside companies by Swiss competition laws – ETA was in a monopoly position, and as such, it was not allowed to stop delivering supplies abruptly. The value of a single watch movement is much less than the value of that movement all cased up inside of a complete timepiece.

It is believed that the Swatch Group simply calculated that it could make more money by selling ETA’s movements inside of its watches as opposed to selling them to third-party competitors at wholesale prices. Further, the early 2000s was when developing nations such as Brazil, China, Russia, and India were experiencing vast growth. Russia and China in particular were looking like very fertile grounds to sell luxury products such as watches. The Swatch Group – as a publicly traded company with shareholders – probably saw the act of shifting ETA production capacity to its own brands as being a wise economic move. Not only did it mean its own brands could boost available inventory, but it likely meant that its competitors would have to raise prices with more expensive movements or be forced to shut down entirely.

I’ve always had mixed feelings about the wisdom of ETA’s ceasing to supply movements to companies outside of the Swatch Group, but I’ve never faulted what I believe was their logic behind the move. If anything, I felt that the decision was equally likely to boost long-term profits as it was to reduce them. By ending its supply of necessary components, ETA was just inviting (in fact they were vocally encouraging) competition to come in and thus embolden the brands it once supplied. I always felt that there was a very strong argument for ETA to maintain its monopoly as means of the Swatch Group maintaining a high level of control on the growth of its competitors. That, however, is a different discussion altogether.

It took many years, but the Swatch Group more or less had its way and can now dictate what ETA sells and to whom. It told the rest of the watch industry to pony up money to fund the production of watch movements themselves – and I think the result was much grander than they could have imagined. The short story is that the watch industry ultimately more than welcomed the Swatch Group’s challenge. It went above and beyond, taking money from strong places to rebuild a vast array of manufacturing muscle that had all but ended a few decades before.

The Fiscal Reality Of Becoming A Manufacturer

If you were a company that bought movements from ETA to put into your watches and were suddenly told that ETA was stopping supply… you essentially had three options. Option one was to purchase movements from elsewhere. Option two was to explore making your own movements. Option three was to shut down or sell your operation. Each of these options was adopted (possibly equally) by a range of companies in the last decade.

As I mentioned earlier, ETA had a more or less total monopoly over the production of mass-production-priced, “Swiss Made” mechanical movements. In the early 2000s if you bought from ETA, it wasn’t as though you could call up someone else and get an alternative product for a similar price. Sure, there were smaller, more boutique Swiss movement makers that would charge you a lot more, but if you wanted something like a stock ETA movement, you had pretty much one option: ETA. At the time, alternative movement makers existed in China and Japan. Not only did these movements typically not look or perform as well, using them would deprive a brand of the valuable ability to put “Swiss Made” on the dial of a watch (though workarounds were found by some).

It is unlikely that the Swatch Group did not anticipate competitors emerging. In fact, what made the creation of competitor watch movement makers so likely was that almost nothing ETA produced was protected by intellectual property patent rights. The movements they make mostly use architecture and technology whose patent protection rights had long since expired. What ETA and related Swatch Group suppliers have is talent, machinery, and knowhow. It probably banked on these factors as being difficult for the competition to acquire in sufficient speed or at reasonable cost to be a threat.

Relatively soon after it became clear that ETA would stop supplying movements, Sellita was formed with fiscal backing from some major brands to produce clones of ETA movements. After Sellita, a few other companies began to form, each with the same tactic of producing clones or replacements of ETA’s most popular movements. Moreover, Japanese movement makers such as Miyota started to seriously up the game of their offerings. It was thus only a few years before competitors existed that were able to sell replacements at acceptable prices for what many companies had relied on ETA for just a few years earlier.

This meant that many of the smaller watchmakers that were threatened with extinction by ETA no longer supplying movements were offered pretty good alternatives relatively quickly. These were the companies who opted for “option one” above, meaning that their post-ETA survival plan was to purchase movements from other suppliers. However, from a marketing perspective, these brands would also remain either boutique or relatively modestly-priced compared to the watches produced by Swatch Group-owned brands. From this perspective, the Swatch Group’s goal was extremely effective. That meant Swatch Group brands like Longines and Tissot would set the bar for how much money certain types of watches could be sold for without seeming overpriced.

Where it gets interesting is what happened with the companies that opted for option two, and that was to take ETA up on its challenge to produce their own movements. Faced with this dilemma, many Swiss watch brands needed to rediscover their pasts, back when they used to make their own movements. What many of these brands quickly realized was that setting up a factory was both extremely expensive and extremely tricky.

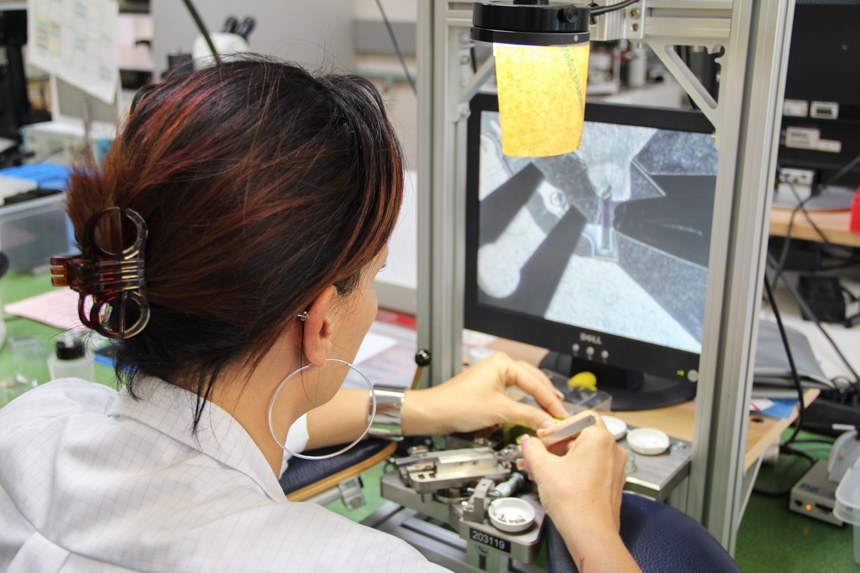

Just when it was widely assumed watchmaking as a profession was about to die out, there was a new call for watchmakers. For many people, watchmaking school over the last 20 years has even been totally free (even in America, though personal expenses and materials are not covered) given the demand for labor. The surge in high-end watchmakers needing to produce their own movements had the obvious side-effect of increasing demand for watchmakers and other technicians ranging from machinists to industrial designers. For a few years in the mid 2000s until quite recently, all you heard about was factories expanding, new movements being released, jobs being created, and new brands “rediscovering their heritage” and releasing old products in new ways.

What was less talked about was where all the money for this was coming from. Remember that to a large degree the mechanical watch industry was a cottage industry, producing high-quality enthusiast items for people who liked the feeling of wearing a high-end mechanical watch. Suddenly, the industry at large started to need a lot of money to build things, hire people, and expand. Thus, not only did expenditures soar, but so did the demand on profit performance. The costs of doing business for many watch brands likely doubled if not tripled or quadrupled in light of taking the “Swatch Group challenge” and building their own movements.