The Isle of Man is an island off the coast of the UK mainland that is not known for many things except perhaps the TT races and also as a place for lower tax rates.

If, however, you are well versed with high-end watch-making, you will instantly know that this is the place where significant things have happened in the world of horology. This is after all, the place where the late George Daniels had his workshop as well as where his protégé Roger Smith is currently carrying on and continuing his legacy of the English hand-made watch.

My visit to the Isle of Man was something of a personal pilgrimage due to the utter uniqueness of the watch-making history that has transpired there. While the Swiss have dominated the watch industry in more recent times, it was from the mind and imagination of one man, George Daniels, celebrated as the greatest watch-maker since Breguet, where an overturning of conventional ideas had begun, establishing at the same time, an outpost in this unique place where an alternative history could be written.

This is especially so if you are British and have a reminiscing bent towards the proud watch-making heritage that originated here with the Marine Chronometers of John Harrison in the 1700s. You might even, on account of nationalistic pride, bemoan the gradual loss of this watch-making heritage. Do know however, that Roger Smith’s studio stands as a beacon of hope for a gradual resurgence and as the continuation of the legacy of George Daniels.

No one denies the influence of George Daniels, one of the few people in history who have created an entire watch by hand. Witness the number of independent watch-makers these days, (of all nationalities), who cite the Daniels reference work “Watch-making” as a foundational part of their education. Without doubt, the one person who holds the direct lineage to the work started is Roger Smith, whom I had come to meet today.

I arrived at the tiny wind-swept airport in the Isle of Man in a 78-seater Bombardier, the type of plane with propellers, in a place served mostly by small planes and by a three to four hour ferry ride from the UK mainland. Waiting at the airport to greet me was Roger Smith who I instantly recognized from the documentary, “The Watchmaker’s Apprentice”, which was first screened at the Salon QP in London in 2012.

Getting into his car, I was taken through a landscape of hills and fields as far as the eye could see towards the north of the island. It seemed that as the car moved further and further inland, the isolation of this place became more palpable. If you’ve visited watchmakers before, you will know that they like to locate themselves in remote places where full concentration is possible.

This is an isolation that brings with it a certain rhythm of thought, where distractions by virtue of location are eliminated, and where the carefully considered actions of the watchmakers can come into full bloom in the creation of outstanding pieces of horology.

Arriving at the Roger Smith studio, I was confronted by a cottage in the middle of fields on which there wasn’t even a sign on the door bearing the company name. The low profile nature of the facilities was a deliberate choice for Roger, not wanting to be disturbed too much from his work.

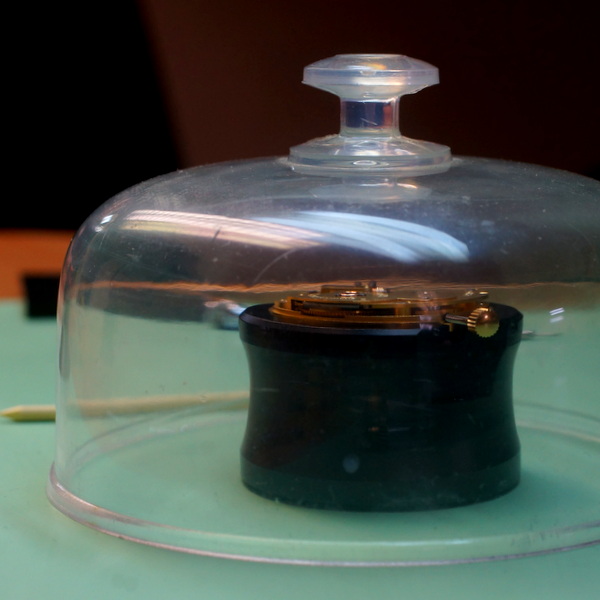

Truly a cottage industry, literally and figuratively, I found within the small building the two main areas where the watches were made, the machine room and the assembly area. The machine room is where the parts are fabricated and where the processes requiring large machines are performed, such as dial engine turning and case fabrication.

In the main studio area, it was the more familiar sight where I found three watchmakers assembling movements in a comfortable, quiet space where time seemed to stand still.

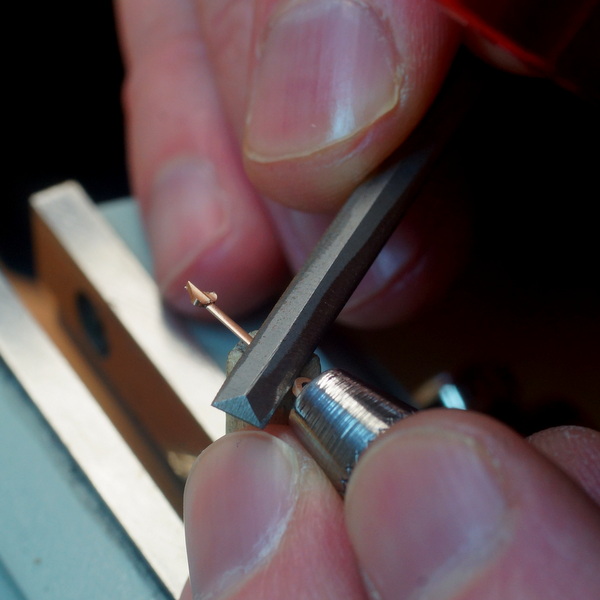

On the workbenches, I was able to see a Daniels Anniversary and a Series 2 in different stages of progress. As each watchmaker worked, with the sound of the radio in the background, I saw the polishing of small parts, the fitting and regulating, and sometimes dis-assembly of the movement and otherwise various minute tasks all in the service of attaining perfection in the watch they were assembling.

There was clearly no haste and no rush to get the job done. All I could see was a concentrated and methodical series of actions that flowed logically one into the next. I felt my heart rate slow down watching them, and it helped that there was a vast green landscape outside to further induce my sense of relaxation.

What makes the watches that come from this studio so unique? Well, small numbers for one thing. Only ten or twelve pieces are produced a year, and this is by no means a conceit of purposely limiting numbers to create an artificial exclusivity. The small numbers speak to the amount of effort and man hours that goes into each and every watch.

A watch that comes from this studio is more than a functional object. Beyond its intended use as a timekeeper, the quality of the finishing and the components is paramount as well. As George Daniels once said, “A handmade watch has to be as good as, and better than a mass produced watch.”

I was able to see with my own eyes how carefully the watches were put together. From the fabrication of the individual components, to the extraordinarily labour intensive engine turning for the dials, to the careful polishing and finishing during the movement assembly process. What I was able to see was merely a small fraction of the total number of steps taken towards a finished timepiece.

Just to give you an idea of the time required to make a handmade watch, look at the following list taken from the specifications of the Daniels Anniversary.

Movement: 16 weeks / Case: 2 weeks / Dial: 3 weeks / Hands: 1 week / Deployment Clasp: 1 week

This is under the assumption of course that nothing else is done. Practically speaking, this time is spread out as other tasks are done concurrently. The finishing process has to be the part of the creation of each watch that is the most time intensive. Every part, aside from functioning correctly, has to be beautiful as well.

The number of hours that is spent on perfecting each piece is truly extraordinary, and for all the bluster that big brands make about handcrafting their watches, the truth is that hidden away from the marketing messages are big machines that crank out parts like any modern assembly line. In stark contrast to the method that Roger Smith uses to make his watches, it is night and day.

Daniels Anniversary Watch Dial Close-Up

The handmade watch is truly a thing to behold. Handmade objects always retain the idiosyncrasies of the creator, which is one of the things that make them stand apart from a mass produced item. Take the dial for instance. Under a loupe you can see how the engravings of the markers are slightly askew, and little things like the markers are not always the same size. These little signs are evidence of a human creator, and much like hand-writing, imbues a personality and character to the watch that hearkens to the days before precision machines existed. Every curve cut into metal was directed by the human eye and fashioned with tools from the human hand. A laser engraved dial would be more accurate, but it would be like all the others and just not the way that Roger Smith does things.

You could say that it doesn’t have to be done this way, yet one of the goals of Roger Smith is to bring back the level of quality that he first perceived in old English pocket watches that simply cannot be found in mass produced watches of today.

Looking at it like that, the base price of 84,000 GBP for a Series 2 watch doesn’t really seem that outlandish given that what you get is a handcrafted object that truly reflects the cost that went into making it. If you hold a Roger Smith watch in your hand, you will perceive the huge number of man hours that went into creating it.

I found Roger Smith himself truly a personable character, open and willing to explain everything that I wanted to know about him and about his watches. I found him as well, a man on a mission in what he had set out to do, and doing it in an extremely principled manner in the way that he had chosen to make his watches.

A tinkerer of watches since he was very young, he started taking watches apart to see how the mechanism worked. At 16 years of age, studying at the Manchester School of Horology, George Daniels happened to come by to give a lecture. It was during this fortuitous meeting that he was shown the “Space Traveller” watch, one of the seminal pieces of George Daniel’s career that recently sold at auction for 1,329,250 GBP. It is an 18k yellow gold chronograph with a Daniels independent double wheel escapement, mean solar and sidereal time, age and phases of moon and equation of time; in short, a very complicated pocket watch and a masterpiece by any measure.

This moment had struck him deeply, as this watch that Daniels revealed from his pocket was the finest watch he had ever seen in his life even until now. That meeting cemented in him the idea of what he wanted to do with his life, and strengthened this resolve to become a master watch-maker.

After that, he sought an apprenticeship with George Daniels, who initially refused as he wasn’t in the habit of taking on apprentices. Roger was told instead to use the book “Watch-making” as a guide to make a watch by himself. A self imposed apprenticeship period of seven years began in which he started to perfect his mastery of the 32 out of 34 skills traditionally used in the making of old English pocket watches.

The first pocket watch he made took two years, and despite being praised as a good attempt, was criticized for looking too handmade. His second pocket watch took five years to complete, and featured a one minute tourbillon, detent escapement, and a four year perpetual calendar. This watch was praised as a success by George Daniels.

As the collaborations between master and apprentice became more frequent, Roger moved to the Isle of Man and eventually established his own studio in 2001.

The final collaboration between apprentice and master was the Daniels Anniversary, a project started in 2010, and conceived to celebrate the invention of the co-axial escapement in 1974. Limited to 35 pieces and utilizing a brand new movement, this was to be George Daniels’s final contribution to horology. In fact the prototype was completed just weeks before he passed away. On the day when Roger brought the prototype in for examination, he was surprised to find that Daniels had no criticisms of it.

If anything, this fact alone shows the absorption and mastery of everything that George Daniels had to teach, symbolizing as it were, the complete transfer of skills from master to apprentice.

When I asked Roger about his relationship with George Daniels, he described it as a guarded one. It was not to say that they were not close but there was always a distance between them that was, I suppose, governed by the serious nature of the work they were doing together. George Daniels came across to me, as the epitome of individual will personified. The watch-making principles he espoused were so thoroughly ingrained through a lifetime of achievement that it was only natural that this strength of will was absorbed by Roger so thoroughly as well.

In fact through my conversations, it was as if I heard George Daniels speaking through Roger. If you’ve ever watched video interviews with George Daniels, you will probably get the sense that he was a non-nonsense individual who did not suffer fools gladly.

While Roger Smith is achieving great things in horology right now, I believe that his greatest achievement must have been to have the courage to approach the straight-talking George Daniels in the first place for an apprenticeship, and then continuing on to endure, in his watch-making education, the often pointed criticisms of his early work by the master.

In many ways, the world of horology must be thankful for this fortuitous event, for in my estimation, given what I know about George Daniels, he does not seem the type of personality that would have gone out of his way to find an apprentice for himself. How much poorer the world of horology would have been, had the skills he accumulated over a lifetime were not directly transmitted to the next generation?

Daniels Anniversary Watch

Through the efforts of Roger Smith, watch lovers around the world, are able to buy and own a George Daniels watch, either through the Daniels Anniversary or through a Roger Smith watch, all tracing their lineage to George Daniels and his method of watch-making. Before Roger Smith, it was well nigh impossible to acquire one of the original pieces from George Daniels when he was alive as he sold only a few of them, and mostly kept the rest for himself. Certainly now as well, these original pieces are even more difficult to acquire since they have gone into collections world-wide after the very successful “George Daniels Horological Collection” sale by Sotheby’s last year in November 2012.

Make no mistake though, a Roger Smith watch is an exclusive object, and available though it is to those who can afford one, they are still extremely rare.

Currently on offer from Roger Smith are the Series 2 and the Daniels Anniversary, with special commissions possible as well. However as of the date of this article’s publication, be prepared to wait up to eight years for delivery for this bespoke option. The more standard options offered by Roger will take at least two years for delivery. To date, Roger Smith has delivered a total of under 50 watches to customers since the company was started.

The Series 3 meanwhile, is currently under development and will be launched next year. The long term plan, as Roger described it, is to develop a range of different models and build up a body of work that fully expresses the Daniels method and something that he can be proud of.

As an independent watch-maker, Roger Smith is unique in that his entire watch-making education and career has had no links whatsoever with the Swiss watch-making industry. His is a career grounded firmly in the English tradition and as such could be conceived as a seed in the re-emergence of a true British watch-making industry.

Purely and simply, his aim is to produce watches in the English style and create modern interpretations of the reliable and strong watches that were the defining characteristics of English watchmaking at its peak.

In fact, one of the words that he uses quite often in describing his watches is “strong”. For him, there is a great emphasis on reliability and longevity, resulting in a thicker plate for the movement, and a sense of designing the parts in order to endure a lifetime of service. A tourbillon watch he created for example embodies this principle, as he told me that this was not a fragile tourbillon, but one that he had designed to be as robust as any other component in his watch. The goal he said was to have the watch leave his studio, and come back maybe for a service many years later.

The Englishness of his watches also shows in the somewhat understated design of the range. The main parts of his movements, for example, are covered in a frosted finish, and accented by black polish at the edges. To the eye, the movement looks simple and fairly un-adorned, without the usual flourishes found in other high-end watches.

For those keen to see the quality of the finishing on the movement through skeletonized watches, you will be disappointed as this is not in the DNA of the Roger Smith brand due to the fragility of such a movement. The only concession to this kind of appreciation is the open dial version of the Series 2, that allows one to see the under dial works.

As a point of interest, I noticed when I first met Roger, that he wasn’t wearing a Roger Smith watch on his wrist. When I asked him why, he responded by saying that he doesn’t wear one not because he doesn’t want to, but because he produces so few a year that he doesn’t have the time to make one for himself.

When I told him that he could make a simple functional one without the effort of the decoration, he responded by saying that this watch wouldn’t be a Roger Smith watch at all.

Well, that surely says it all about the principles he is firm on with regards to the quality that his name on the dial stands for.

So what does he wear? Well, you’ll have to meet him yourself and look at his wrist because I’m not going to tell you.

Although I will tell you this: if you see a Roger Smith watch on Roger Smith’s wrist, then there are two possibilities. If it looks brand new, it is probably being tested for a client as part of the two week adjustment and regulation process before delivery. If it looks worn in and used, then Roger Smith has probably found the time to make a watch for himself.

Judging by the success he has had and continues to enjoy, I’m sure that day will come. rwsmithwatches.com