It’s true that Seiko’s Spring Drive movement can divide opinion, as it stands on the border, with a foot in the province of the mechanical, and the other foot in the province of quartz. This hybridized movement may polarize watch lovers, but its detail and craftsmanship are unifying. Watching one of the few people in the world capable of assembling the hundreds of miniature components into this feat of Japanese horology quietens the debate of the Spring Drive’s significance in the watch world, but it doesn’t silence it. With the aid of a true oracle in watchmaking, I explore the makeup of the Spring Drive movement, and whether it can truly appeal to both the mechanical movement followers and the staunch disciples of quartz precision.

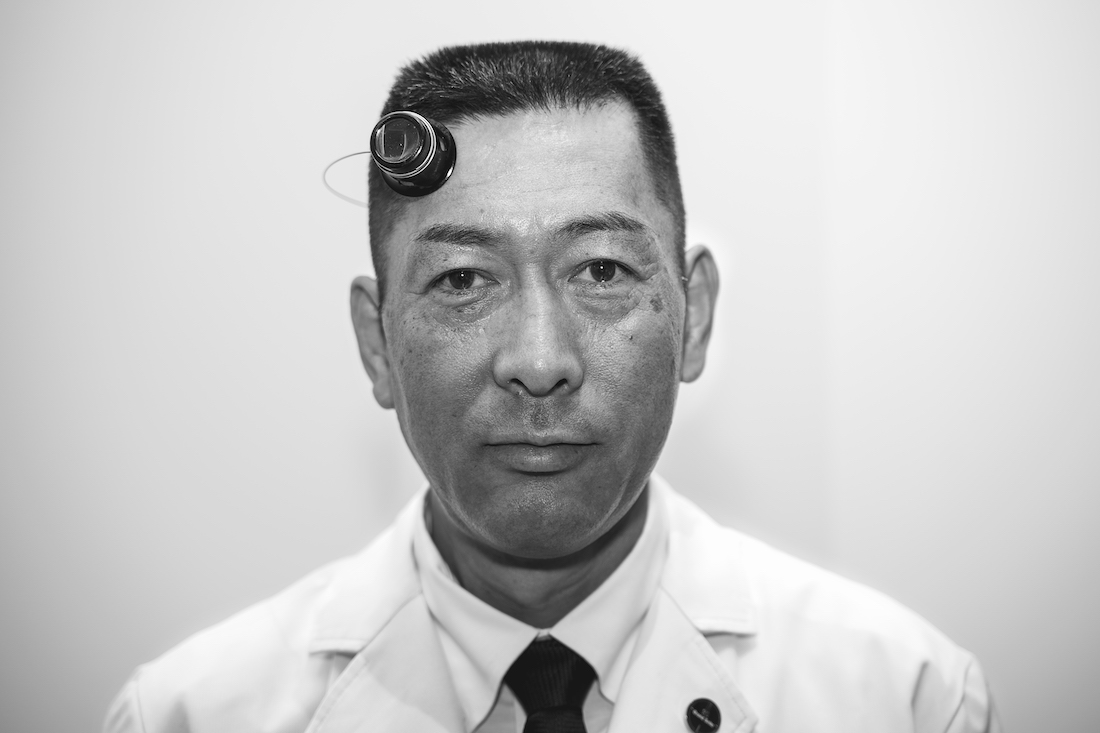

To become artisanal of any craft requires a dedication few of us can achieve. To become one of the world’s leading watchmakers requires such dedication to be paired with exceptional patience, and a steady hand. Yoshifusa Nakazawa, Grand Seiko’s master watchmaker, is all these things and so much more.

Established in 1960, Grand Seiko has spent over fifty years as one of Japan’s treasured and revered watchmakers, assembling beautiful pieces by hand. Within this prestigious brand is a subsect of highly talented watchmakers in The Micro Artist Studio in Nagano. Here, captivating works of horological prowess are carefully handmade, including sought-after Sonnerie designs with their tiny chimes. This team is lead by a veteran of the craft, Mr. Yoshifusa Nakazawa, who I had a chance to meet and observe as he demonstrates his skill set for me in Japan House, London.

Mr. Nakazawa is in many ways, exactly like I expected; quiet, refined, concentrated, and precise. From a young age, he has been obsessed with all things intricate and took up making origami cranes from minuscule pieces of paper. This interest meandered to other small objects, and eventually to the taking apart and rebuilding of watches. After decades of focussing on the art of watchmaking, he is now undoubtedly one of the most skilled and successful watchmakers in the world.

Mr. Yoshifusa Nakazawa is a certified 1st-grade skilled craftsman in watch repairing and an instructor of watchmaking in Japan. He won the 1981 gold medal in the World Skills International Competition, and his continued work in the field lead to the highest forms of recognition from the Japanese government: the title of Contemporary Master Craftsman in 2008, and in 2015 he was awarded the Medal with Yellow Ribbon by the Emperor of Japan.

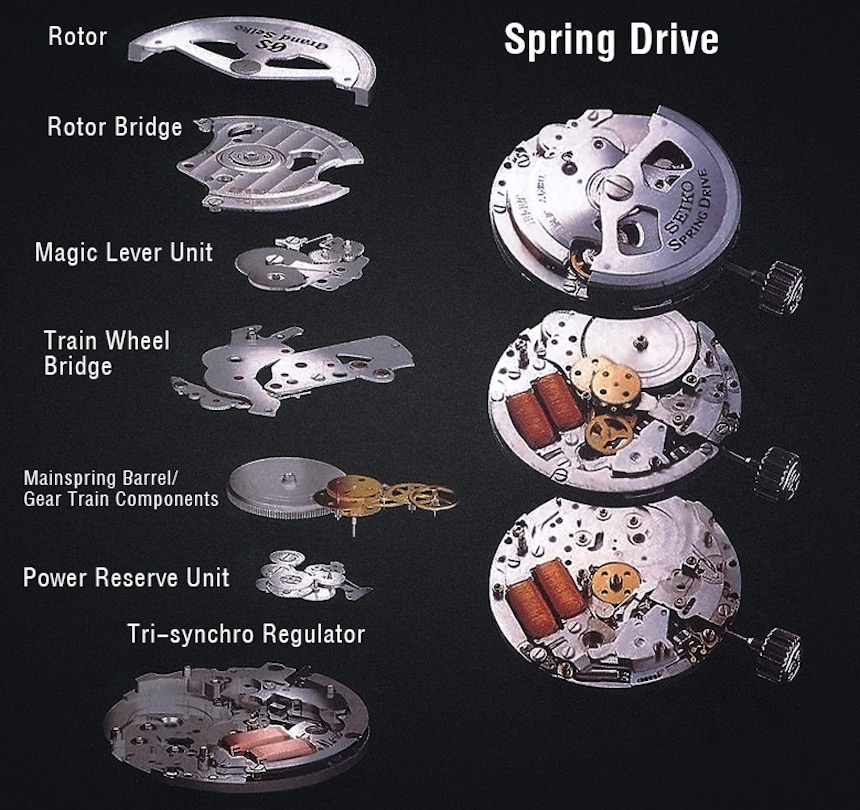

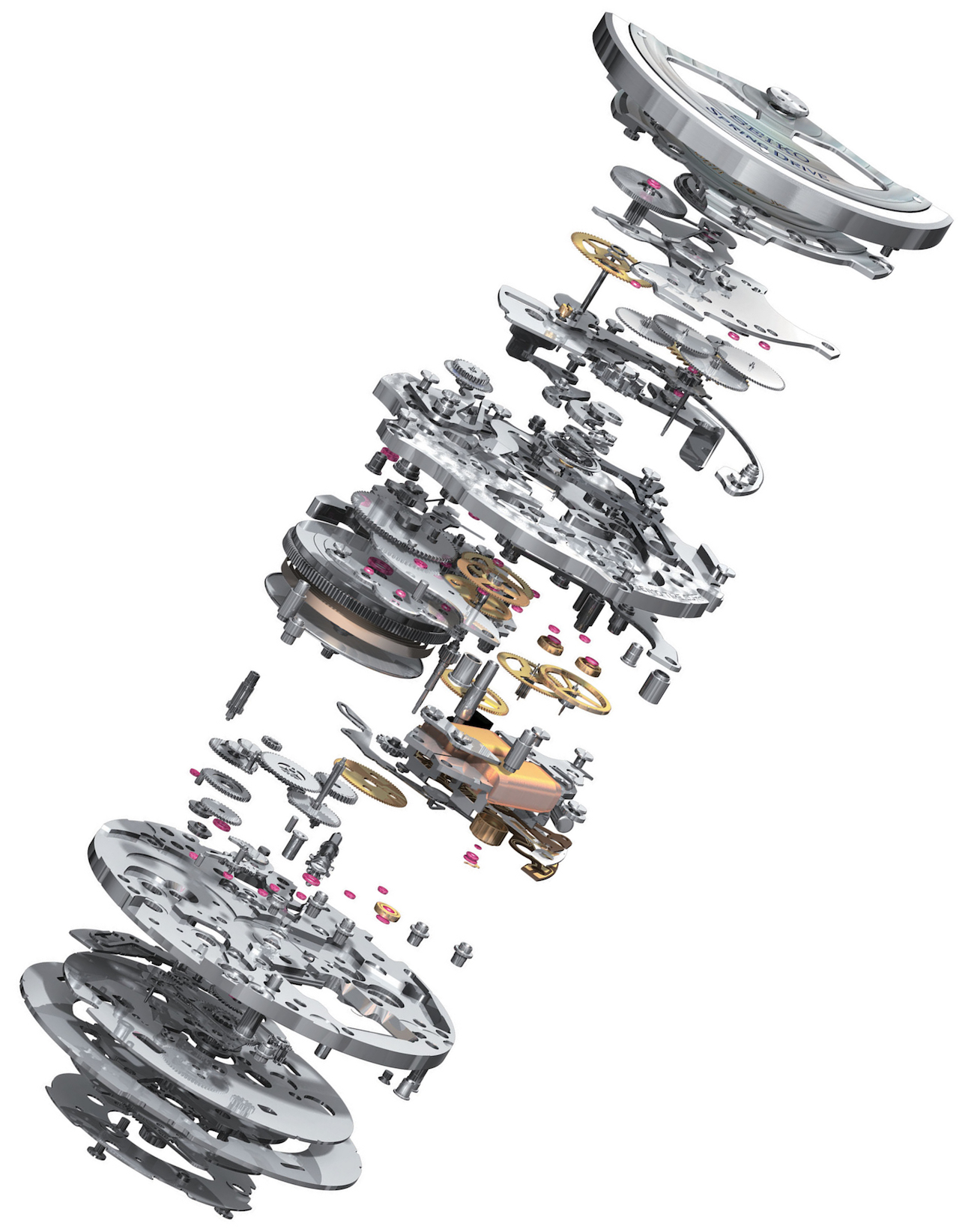

Arguably, Mr. Nakazawa’s specialty as a watchmaker is Grand Seiko’s famous Spring Drive movement. The 9R Spring Drive blends the craftsmanship and allure of a luxury mechanical movement, with the unmatchable accuracy of a quartz, electronically regulated watch. The autonomous power of the Spring Drive movement is derived from a mainspring that you’d typically see in a mechanical watch.

However, the time control system is instead in the form of a Tri-synchro Regulator, comprised of three constituent parts: an IC (Integrated Circuit), an electronic brake, and a quartz crystal. Concisely put, the mainspring unwinds to mechanically create electrical power, the Tri-synchro Regulator transmits a signal through the quartz crystal oscillator, and the IC applies a brake to control the speed of the glide wheel, keeping the time precise.

The Spring Drive movement clearly has a lot going for it, but does it really bridge the gap between the precision of quartz, and the nostalgia of mechanical? I readily admit I don’t wear quartz watches. I am a part of the group that revels in the craftsmanship of mechanical pieces and enjoys the gentle whirr of their parts. But it is difficult to argue the benefits with someone who prioritizes precision in their timekeeping, particularly when I value that too.

So, does the Spring Drive appease both camps? I think it does, yes. The perfectly smooth rotation of the second hand is beautiful to behold, and for me, one of its chief selling points. The intricacy of the hand-assembled movement appeals to my nostalgia for a time where supreme craftsmanship was the only solution for an accurate watch. Hundreds and hundreds of prototypes and patents, two decades, and unthinkable time spent propelled this movement to market. It required the sort of obsessive developmental work by Yoshikazu Akahane of Seiko Epson that swells a pride in any owner of a Spring Drive watch.

Perhaps it takes due diligence to research the movement before anyone is likely to stand in line behind Grand Seiko, but once properly understood that this is a spectacular engineering feat resulting from almost a lifetime’s work, it’s difficult to deny the allure. The general reception of Grand Seiko Spring Drive watches always seems to be largely positive, but it’s not unanimous. I’m interested to know why some people turn their noses up at these pieces. I suspect, while unlikely to be articulated as directly, it’s simply that it’s Japanese as opposed to Swiss; a disappointing albeit not uncommon approach to horology. I would gladly wear a Grand Seiko Spring Drive, and for anybody silly enough to ask about the watch I am wearing, they will be promptly bored with why I am so enamored with it. My thoughts aside, the following is my interview with Yoshifusa Nakazawa.

aBlogtoWatch (ABTW): I understand it took decades to develop the Seiko Spring Drive. Was there a point at which the company was ready to give up on it?

Yoshifusa Nakazawa (YN): It took over 20 years in total. The first idea of Spring Drive was born in 1977. A movement designer in Suwa Seikosha (today’s Seiko Epson), Mr. Yoshikazu Akahane wanted to create a watch that had the accuracy of quartz but required no battery nor rechargeable battery. In 1977, he came up with the idea of a watch that was powered by a mainspring but that had an electronic regulator in place of an escapement. He imagined an electronic brake that would work like the brakes on a bicycle coasting down a slope. At that time there were other priority projects in the company and so he started an underground project with junior engineers in 1982.

Soon the first prototype was made but the project was put on hold because they could not solve what Akahane called the ‘energy balance’ issue. The prototype generated too little power and the IC needed too much. However, Akahane never gave up; he simply had to wait for the technology to become possible. Seiko’s Kinetic technology, launched in 1986 was an important stepping stone in more efficient power generation but the real breakthrough came in the late ’90s when the Semiconductor Division of Seiko Epson came into the project. They helped to produce an extremely low power consumption IC. It consumed only 25 nanowatts; 100 times less than the first prototype. Finally, a working sample was introduced in Basel in 1998 and the first Spring Drive watch was launched in 1999.