Other dial components, such as the Konstantin Chaykin logo or the extremely finicky and delicate mouths, as well as the eyes and moon phase discs also had to be produced in house. Why? Because no one Chaykin could convince into at least a prototype run could ultimately deliver, irrespective of the cost. Chaykin told me that he ended up trying a European dial manufacturer who, after saying they’d charge €500 per dial, ended up simply not being able to manufacture it anywhere close to the required tolerances and levels of quality. (If there are sufficiently capable dial manufactures in Europe for a task like this, they are all privately owned and no longer perform work for third parties). The dial, as it is now, is so delicate, so time-consuming and, consequently, so costly, that Chaykin likes to assemble these himself. Having produced levitating time displays, jazz music box wristwatches, and other uniquely complicated pieces, the fact that this dial can occupy him says a lot about its complexity.

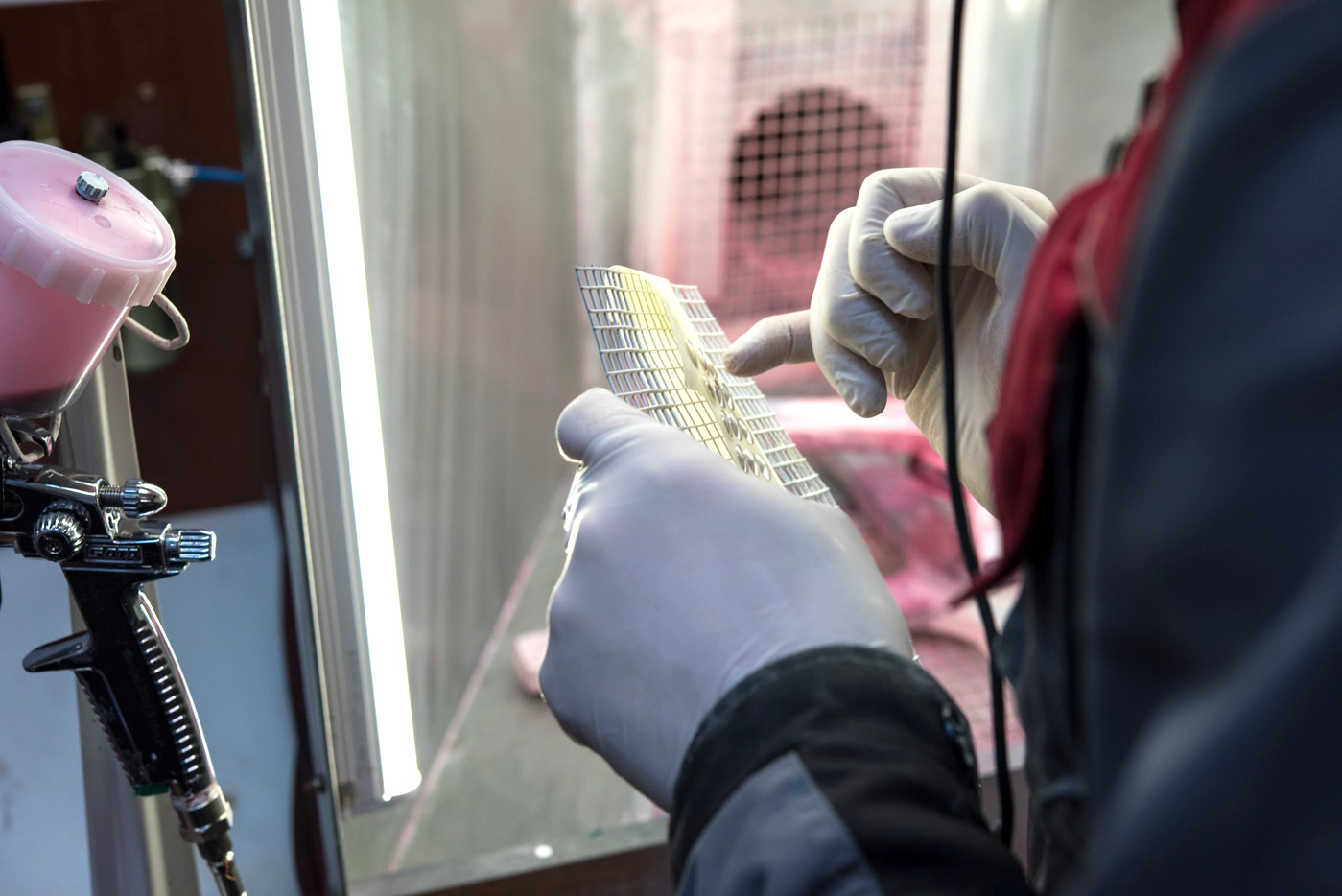

The discs for the phase of the moon display (inside the mouth) and the hour- and minute “eye-displays” are painted by hand in a high-pressure, clean room inside the manufacture — but only after they’d been hand-polished, one by one. The layer of paint needs to be so even and so exacting in its application that only one in ten pieces can be used; these are the components you’ll be looking at most, after all. As obvious as that may sound, if only I had a fiver for every ruined hand that I’ve seen on luxury Swiss watches, I could buy a more high-end Konstantin Chaykin creation.

The case and the bezel are punching way above their weight. A wide, brushed surface is interrupted by 10 notches: five with the French-playing card suits of diamonds (♦), clubs (♣), hearts (♥), and spades (♠), and the letter J over 12 o’clock. The other five notches are arrowheads. The real magic here is in how these are executed. The wide bezel surface is brushed; the arrowhead notches are cut, smoothened, masked around and then sand-blasted to make for subtle, but important and nuanced, variations.

The suits are laser-etched for utmost precision with their backdrops being matte and their raised surfaces polished, so that they stand out against the brushed and sand-blasted areas. Last, but definitely not least, the bottom and top edges of the bezel (the former thinner, the latter taller) are hand-polished to a brilliant, reflective sheen. This process is pictured several images above. The precision with which this bezel is machined and decorated puts so many other bezels in the sub-$10k segment to shame — and many, many others way into the tens of thousands, even. The number of cutting, machining, masking, polishing, sand-blasting operations on the bezel alone, I can say for a fact, exceeds the number of operations some entire luxury watch cases take. (I am looking at you, Panerai Luminor 8 Days).

The Konstantin Chaykin Joker movement is a base ETA 2824-2 caliber with an in-house module on top. What really surprised me when I saw these modules uncased at the manufacture was how nicely made and thoroughly decorated they were. It’s a genuinely neat-looking module, with zero finicky components — everything is nice and large and chunky. The big Konstantin Chaykin Joker text on it is fun, and it immediately made me think how cool it will inevitably look when these are opened by a 22nd-century watchmaker a hundred years from now.

Given the price point and complexity (or relative lack thereof) of the Joker, I am not losing sleep over whether and how this will be serviced. Any capable watchmaker should have no trouble manufacturing new parts for the module, should that be necessary, while the base ETA 2824-2 should remain serviceable forever, really.

The movement works like any other automatic 2824-2: a bit noisy in its tick-tocking, something I could certainly do without, and a short, 40-hour power reserve — you’ve really got to show the Joker some love every other day. There is one small caveat to how the module functions, and that is in the adjusting of the phase of the moon. This is done via a hidden pusher in the left-hand crown. You are not pressing the entire crown but rather the pusher inside it, something you can perform with any pen or pencil, toothpick or other sharp, but non-destructive object.

What the Joker’s manual does, in fact, specify is that the phase of the moon should not be adjusted between around 10 PM and 3AM in the morning, because that is when the indication advances. Dates on some movements function the same way, as it is generally inadvisable to try to adjust the date via the quick-set function of the crown when the indication is being advanced by the movement. What this means in practice is that, should the watch have stopped and you want to set it all up again, it is advised that you set the hands to some time in the “free range,” adjust the moon phase indication and then set the time. This way the mechanism remains safe; breakage isn’t guaranteed otherwise, but this minor extra attention can potentially save the watch a trip back to Moscow.