Today, we are looking at the astounding inconsistencies with “in-house” watch movements and, on a related note, what we, the industry, and you can do to better approach the confusing, tricky, and often misleading matter of manufacture movements. Over the years, we at aBlogtoWatch have published an exhaustive catalog of articles dedicated to the understanding of and debate surrounding mainly mechanical watch calibers, with a special focus on so-called “in-house” watch movements. The time has come for us to re-visit this touchy subject again because, to put it mildly, the proverbial waters are quite muddy.

What The Hell Is An In-House Watch Movement?

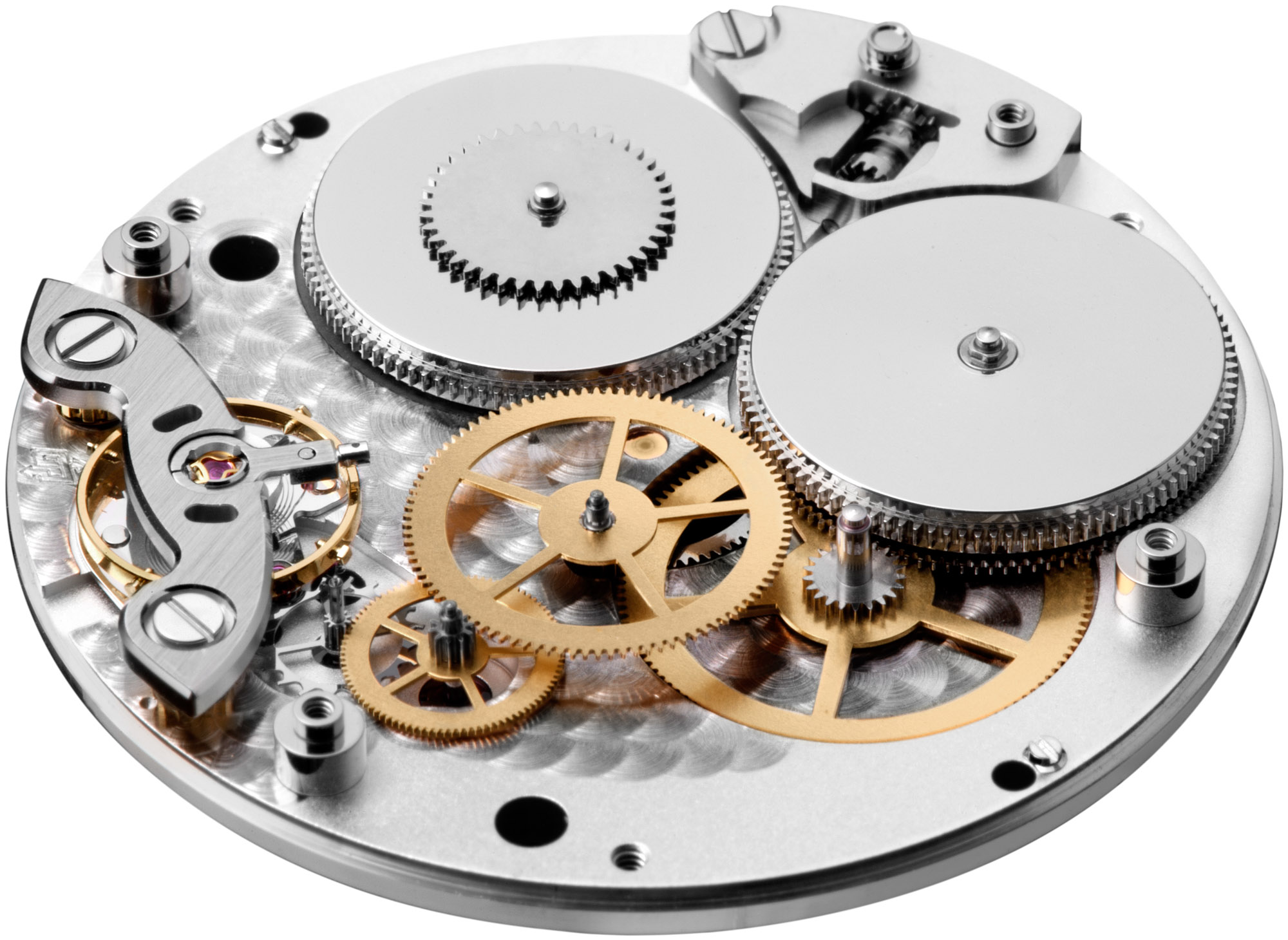

At its core, it’s supposed to be a movement that was both designed and entirely manufactured by the same watch company whose name is on the front of the watch. It can’t really get much simpler than that, right? Following a picturesque train ride through the rolling hills of Switzerland, Germany, or Japan, you find yourself outside a big, old (or big, new) factory building that probably has a fancy family name on it, supported by an improbably old date from two or three centuries ago. It is here, within these walls, that every darn component required to produce a mechanical wristwatch movement should be engineered, manufactured, decorated, sub-assembled, assembled, and quality-controlled.

Here’s the problem with all of that.

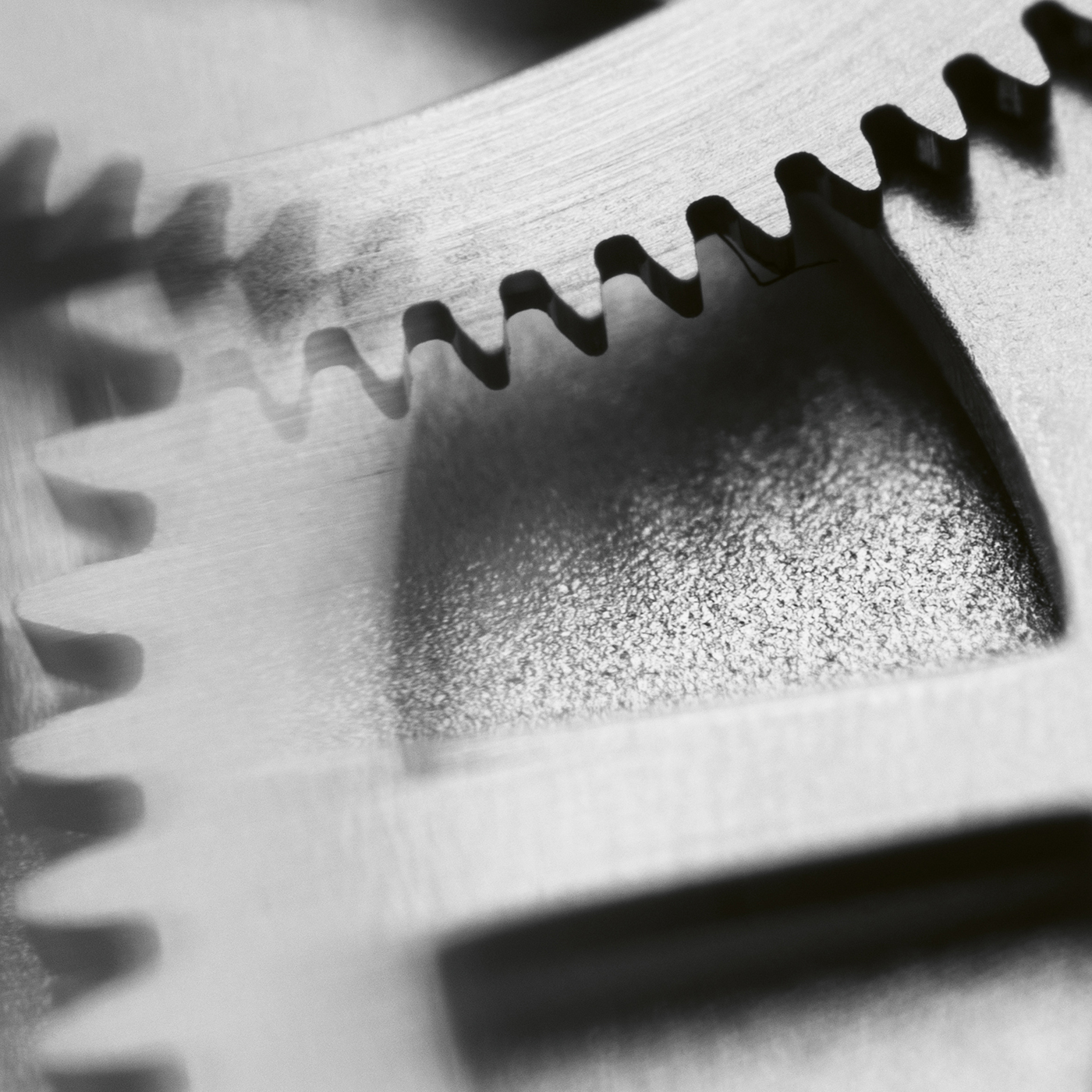

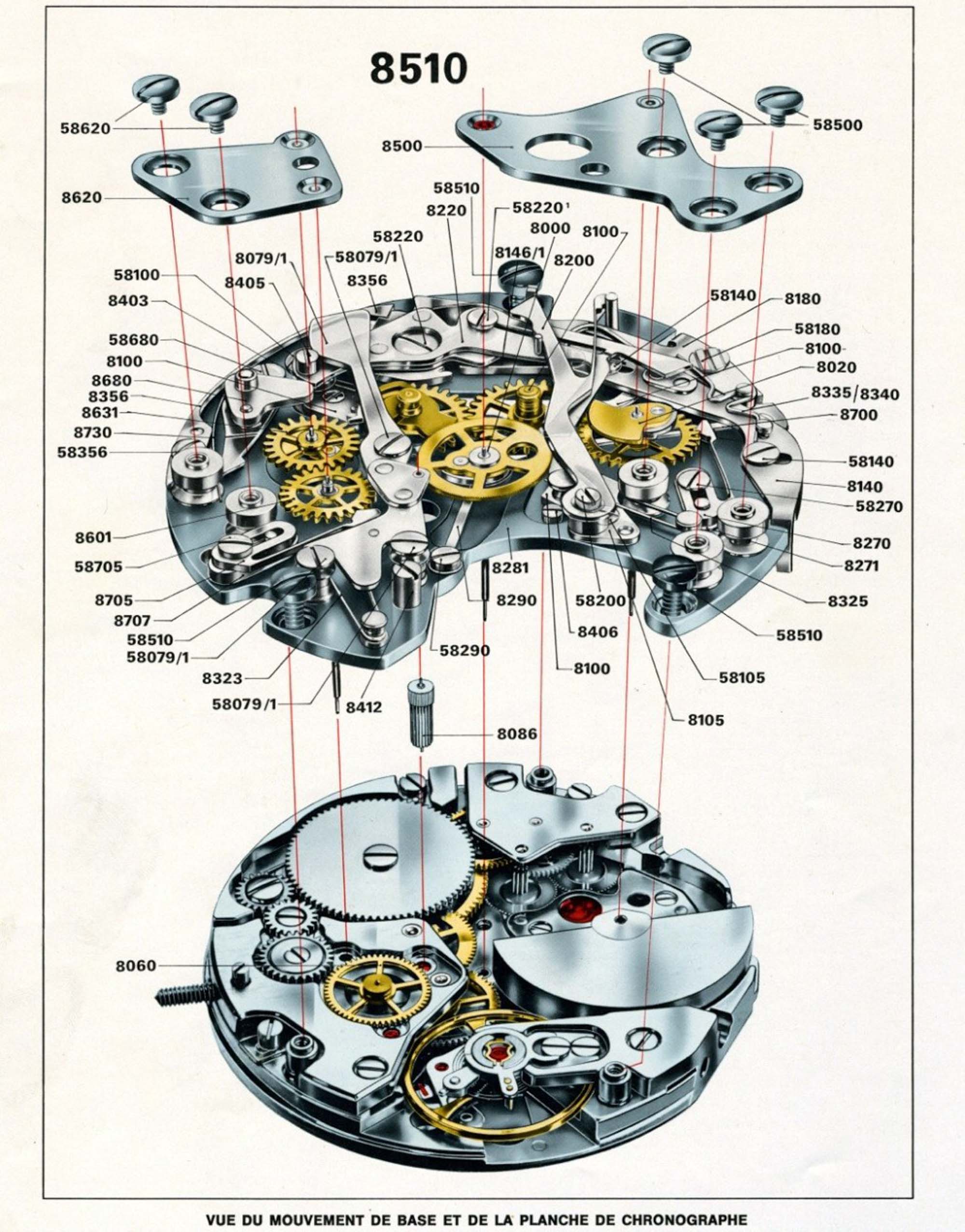

Every wheel, pinion, screw, plate, and every finicky part of the escapement (super-nuanced stuff like levers and pallet jewels and escape wheels and hairsprings), parts that weigh grams, and parts that weigh hundredths of a gram are to be made under the same roof using fundamentally different materials and techniques. The problem is that not too long ago, it used to take nothing short of an entire nation to do what a single building today is “expected” to do.

And so the seen-it-all watch lover who understands the mind-boggling challenges linked to the manufacturing of, say, a balance staff, or a pallet jewel, or a hairspring, quickly begins to adjust their expectations and drift away from that boastful concept of “entirely.”

So, Then, What Is An In-House Watch Movement Really?

With all that in mind, apparently, it is something that is called an in-house movement but is not made entirely in-house, and yet the seasoned watch enthusiast isn’t yet maddened by that. It can’t get much more ambiguous than that, right? So, then, where is the line drawn? There are so many arguments to be made here. Do you draw the line at screws? After all, how serious can a watch manufacture be that can’t even produce the things that hold its movements together, right? Or is it at balance staffs? The incredibly refined and sophisticated part around which the timekeeping organ swivels? Or is it at hairsprings, the component that requires the greatest accuracy in its manufacturing in all of mechanical watchmaking – and the component that is currently produced by no more than maybe half a dozen European factories in any serious quantity?

Empirically, the community seems to have no problem whatsoever with movements being proudly labeled “in-house” even if the screws that hold it together, the balance staff that makes it work, and the spring that allows it to keep time come from a company totally and entirely unrelated to the watchmaker whose name is on the dial. I don’t remember seeing too many heated discussions about the unknown origins of the wheels themselves, either – the parts so unequivocally linked to mechanical watchmaking in the public eye. Apparently, that’s all good, because these are all essential things that nevertheless somehow nobody asks about with any level of consistency when debating the acceptance of one movement as in-house and the heated denial of the manufacture status of another.

So, to answer the question: There is no one definitive answer. There isn’t one because there remains a tremendous discrepancy in what is and is not accepted – with brands perceived to be more historic than others systematically getting a better chance for a pass than newcomers.

Further complicating things are group-owned movement and component manufactures that are sometimes deemed perfectly fine, and other times are not at all tolerated.

Does a modern Omega Speedmaster Chronograph watch with its “OMEGA Calibre 9300” caliber have an in-house movement? It’s probably safe to say that most watch enthusiasts would agree with the official product page when it refers to it as “the first chronograph in the brand’s family of in-house Co-Axial mechanical movements.” Even if Omega insists on calling its Bienne facility a factory and not a manufacture precisely because they – as in Omega – stress they don’t produce anything there. According to Omega. “All steps [sic erat scriptum], including T2 (watch assembly), T3 (bracelets), and T4 (shipping), as well as stock and logistics, will now be completed inside the new building.” Notice how the actual manufacturing of parts isn’t mentioned, which is why, Omega says, it’s called a factory and not a manufacture – why they’d feel inclined to say that “all steps” happen there is another story. The parts come from the insufferably secretive network of Swatch Group-owned specialist manufacturers, a web of excellent and fully Swatch Group-directed watch movement component manufacturer specialists. And yet Omega calls its 9300 calibre and most all other of its movements in-house movements – statements which the community does not appear to take issue with.

Likewise, the Tudor MT56xx range of calibers is both advertised and widely accepted as in-house movements, even if Tudor remains extremely secretive about where and how these movements are produced. Are the manufactures owned by Rolex and not by Tudor? By every chance – along with other reported partial owners such as Breitling and Chanel. Are they actually operated by Rolex and not by Tudor? Most likely. Does the watch say Tudor on it, does MT stand for Manufacture Tudor, and are these accepted as in-house Tudor movements? Check, on all of those. Is there a problem with any of this? Clearly, there isn’t – they are highly specified movements that offer a lot over the supplied ETA movements that came before them. Not even if said movements with largely identical constructions can be found in Breitling (Calibre B20), Chanel (Calibre 12.1) and Norqain (Calibre NN20) watches where they all get to call said movement a manufacture movement and all that gets a pass.

Moving further down the price range but still very much sticking with Swiss watch industry giants: Brands like Hamilton, Mido, Tissot, Rado can all call what is essentially the same movement a variety of things – Caliber 80, C07, Powermatic 80, H-50 – leaving it to the customer to find out (or not) that these apparently competing brands are all offering largely the same movement potentially produced by the same manufacture. One need not dig for too long at these brand’s official websites before they are to find rhetoric that calls this movement their own – if the massive branding on the rotors wasn’t convincing enough. Because it doesn’t take too much imagination to picture the average consumer rightfully considering these movements that are called a different thing and have different branding on them as, well, totally different movements, therefore depicting these brands as watchmakers who make their own movements. And even if all this was not intentional by these brands, we feel it’s safe to say that this practice carries some potential to be, ahem, misleading.

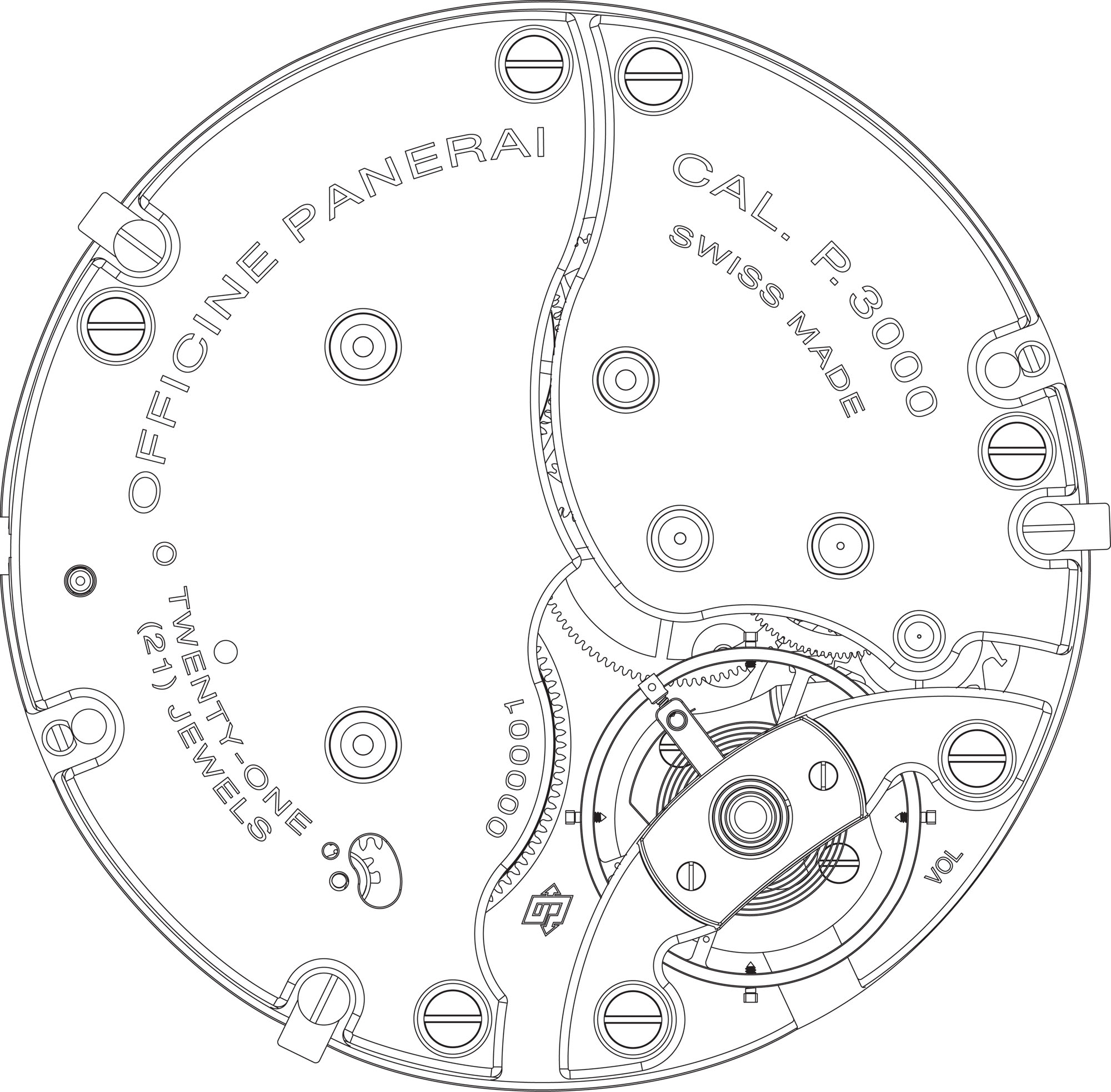

The latest scandal related to the issue of in-house movements concerned Panerai, its labeling of a supplied movement as “in-house” and its reliance on Manufacture Horlogère ValFleurier, a proprietary movement manufacturer operated by Panerai brand-owner luxury group, Compagnie Financière Richemont SA. Panerai has arguably gone overboard with its “executed entirely by Panerai” rhetoric with which it labeled many of its previous in-house calibers, and that practice was recently topped by communicating what seems to be an ETA/Dubois-Depraz caliber as an in-house caliber – a mistake that we at aBlogtoWatch have also made and, unlike Panerai, we have since then corrected. And this neatly leads us to question of what to do about in-house movements.

What aBlogtoWatch Can Do

It is only right that we begin the “what to do” laundry list with ourselves. First, we at aBlogtoWatch will have to exercise greater consistency when assessing the claims of watch manufacturers about in-house movements. Second, we have to regularly publish thought-provoking articles (like, hopefully, you will find this one to be) on the subject. Third, we will have to continue highlighting other, often practically more important, merits of watches – like those we mention further below in the “What You Can Do” segment. There is so much more to a great watch than the origin of (some) of its parts and the perceived status that may yield. Fourth, we shall more consistently distinguish truly in-house movements from exclusive calibers – the latter being ones produced out-of-house but exclusively for the use of one brand within a group. This is a short paragraph of complicated goals we are working toward with diligence.

What The Watch Industry Can Do

Use truthful labeling such as “exclusive movement,” manage customer expectations, and train staff. Labeling and loudly promoting movements as in-house is a fairly new development. While a handful watchmakers have long enjoyed a manufacture status, for literally the first entire century of wristwatches – basically all of the 1900s – nobody really cared that much whether their watch had a movement that was made in-house, that had an externally sourced ébauche movement kit supplied by someone else, or had a movement entirely made by another watchmaker – like Jaeger-LeCoultre, for example. A watch brand’s reputation for overall accuracy, quality, and reliability mattered and not the labeling of a movement as “in-house.” And so, the in-house craze began when Swatch Group-owned ETA, the luxury watch industry’s most relied-upon movement supplier, started reducing the supply of its movements to many watch brands — then stopping altogether.

Said brands had to start heavily investing in their own movement manufacturing capacities — or, if they were part of a luxury group, the group would centralize these efforts in the same way and for the same efficiency reasons that the Swatch Group had. Because the world of luxury brands is about tireless one-uppery, it was only “logical” for brands to communicate their new movements as the best things ever – and so the in-house label quickly became attached to a concept of superiority, often without any meaningful improvements in any measurable technical aspect such as accuracy, power reserve, or reliability.

This resulted in mismanaged expectations in the wake of a self-induced spiral where everything had to be labeled as “in-house,” or “manufacture,” or be presented as though it was “executed entirely” by a brand… Because watch customers around the world have soon been programmed to ask, “Does this watch have an in-house movement?” before shelling out big bucks for a watch. And so, the question was not “does this watch have the most accurate movement / the longest power reserve / the best reliability / the longest service cycle” in its segment, but whether it had an in-house movement because that’s what brands spiraled into communicating as the be-all and end-all in watchmaking. The yes/no binary question sure makes marketing easier than those pesky specifications or the actual refinement in the nuances of a watch movement.

Never mind that a lot of the time, the shiny new in-house caliber couldn’t offer much at all in terms of practical benefits over the ETA 2824 or 7750 that it had come to replace (of course it couldn’t, since it had to seamlessly fit the same case with the same mounting points and match the same dial layout as the ETA it replaced); these movements were often advertised to be better for the simple reason that they were “manufacture” or “in-house” calibers. And so, the watch enthusiast who considers a movement to be better because it was made by a brand over a supplier was born. And if all that you care about is where a movement was made without actually looking for the specs behind that movement, then you will certainly be mad if you learn that this one single thing you cared about so deeply was either completely or partially false.

Third, train staff. I will save them their blushes, but it is true that, over the years, I have heard a great many watchmakers, marketing directors, product trainers, and those in other roles, all at major brands, complain about the lack of product knowledge in one department or another at these respective companies. Watches and luxury watches, in particular, are extremely complicated products with myriads of nuances that often not even seasoned watch enthusiasts can agree about. Newcomers to the trade, even if they had excellent careers in other industries before, often struggle with getting these peculiarities right – even though they are soon expected to fulfill their new roles — which is often in marketing and communications, or in direct sales where they, by design, have to communicate about the brand’s products, including, of course, the movements. This has, in the past, frequently resulted in movements being labeled and openly communicated as in-house either at trade meetings, in official branded messages, or during sales meetings with customers.

What You Can Do

Establish your personal list of priorities when determining the horological value of a watch. There is so much more to a watch than which building its mainplate came from.

Please remember this:

A movement, and more importantly the complete watch itself is a magnificent constellation of fundamentally different components, each designed, chosen, made, and assembled as a result of thousands of considerations and decisions by people whose lives revolve around making that watch for you.

Everything from proportions, materials, colors, durability, comfort and so many other factors make or break a watch – and nigh-on none depend on the in-house status of (or lack thereof) the movement.

While many watch buyers are hardcore watch enthusiasts, it is safe to say that the majority of luxury watches are purchased by folks who are a lot less knowledgeable when it comes to the ins and outs of watchmaking. For them, a nice watch is just a piece in the jigsaw puzzle of luxury purchases, right next to considerations for their upcoming luxury cars, yacht, travel destinations, shoe brands, etc. Not everyone can reasonably be an expert of every purchase they make: pick the exact engine and transmission combination revered by car enthusiasts, know the latest developments in hull hydrodynamics, holiday at the latest posh place where all the stars will hang out this year, and rock the apparel best approved by the fashionista. One can’t be the master of all these things – and yet, one can enjoy all of them.

The point is that it is understandable that a binary “is it or is it not a ‘real manufacture’” question is preferred because it may appear to be the convenient shortcut to make a complex decision rather more straightforward, all of a sudden. But, just as it is with cars, boats, travel, and all the rest of it, making purchase decisions with limited understanding and, what’s worse, with a snobby, status-driven attitude, is hardly ever a good idea. What we recommend is that you buy what you like – for the looks, the style, the feel, the quality, the mechanical complexity, or lack thereof — and buy not what others may consider to be superior, for all the wrong reasons, like where a mainplate was made.

Conclusion

One of the main purposes of this article was to pose some direct questions with regard to the actual value of in-house movements, the hypocrisy (or at the very least, the inconsistency) with which in-house movements are judged by watch enthusiasts. And then shine light at the absolute unfeasibility that stems from this hypocrisy where certain components are sometimes accepted to come from elsewhere, and sometimes they are not.

To end on a personal note: I do not know of, and cannot imagine, a single soul on this planet who has experienced any infinitesimal amount of joy from the in-house status of their watch movement. Better specs like greater accuracy or a longer power reserve or a better-looking movement (which is rarely true for in-house movements that have come to replace ETA calibers, but let’s not even get into this) — these are things many appreciate in a new watch purchase. But the pure in-house status is a moot point at best because it yields no tangible, appreciable benefit to the customer – only the intangible, fleeting, weak glory of bragging rights. And buying a watch mainly for bragging rights is the perfect recipe for growing bored with it soon.

There is a lot that aBlogtoWatch, the industry, and watch consumers can do to clear up the confusion around manufacture calibers. We’d love to hear from you below in the comments on what aspects you agree with and what more we could add to that to-do list that will help us move on from this current state of confusion.