“You can build mass-market products in countries like Switzerland or the United States only if you embrace the fantasy and imagination of your childhood and youth. Everywhere children believe in dreams. And they ask the same question: Why? Why does something work a certain way? Why do we behave in certain ways? We ask ourselves those questions every day.”

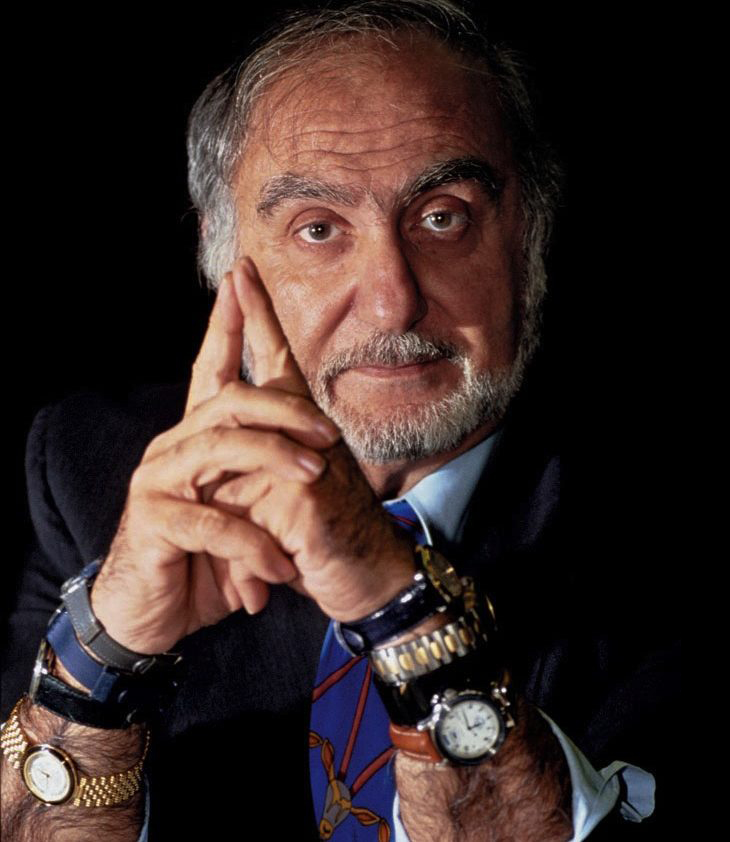

It is known that Jean-Claude Biver worked under Mr. Hayek while he was at Omega. Mr. Biver is the predominant marketing mind in the watch industry, and I think it is safe to say that he was heavily inspired by Nicolas Hayek. In particular because Biver understands the need to make a product that motivates people emotionally. Not everyone understands Mr. Hayek’s lessons like Mr. Biver does.

Fantasy and imagination are easy to dispel as time-wasting or immature. But are they when it comes to product design? Especially in something as personal and communicative as a watch? While there are many ways of implementing emotional appeal into a product, I think it is safe to say that if you foster a culture that celebrates imagination and fantasy, you are going to come up with a more emotionally compelling product than if you give someone a sober design brief and marketing prompt. Let watches be designed the way Hayek would have preferred.

“SSIH had no discipline and no strategy. It had its own distribution in countries like Germany and France. It worked through agents in other countries. It even let some agents contract with outside manufacturers to build their own Omega models! It made no sense.

Then there was ASUAG, a company with Swiss-German origins. ASUAG was a manufacturing company. ASUAG owned a few brands, including Rado and Longines. But its heart and soul was an operation called Ebauches S.A., which supplied components to the whole Swiss watch industry. Ebauches was very capable. Over the years, however, as various small Swiss brands faltered, they went to ASUAG looking for a rescue package. ASUAG was the rich uncle: “Please, we are going broke. Why don’t you buy us? It won’t cost much. You can’t let us disappear.”

Hayek here is referring to the state of the Swiss watch industry at the time he entered it. SSIH and ASUAG were merged to to create the Swatch Group. Hayek points out a lot of interesting facts here, but importantly how they lacked any central focus, leadership, or even direction. He also mentions a lack of discipline and strategy, that I think a lot of people would claim is present in the watch industry today.

I also see parallels here to the current watch industry distribution market which in many ways is just as fragmented. Even if brands have wholly-owned subsidiaries in other countries, most of the time those subsidiaries are treated like third-party companies, but also not given an ability to control their actions like third-party companies. We also see Hayek pointing to the fact that the brands were seeking outside help and to be rescued. We know that watch brands today rarely act without “expert advice” or a proposed direction. Hayek realized that the watch industry needed a direction, a purpose, and a strong, decisive leader – few things that most Swiss watch brands can really claim to have today.

“The Swiss share of the bottom layer, 450 million watches, was zero. We had nothing left. Our share of the middle layer was about 3%. Our share of the top layer was 97%.

We were cornered. The Swiss spent much of the 1970s reacting to quartz by retreating: “Why should we compete with Japan and Hong Kong? They make junk, then they give it away. We have no margin there.” Of course, as we retreated, the Japanese moved up to the next layer of the cake. Then the retreat would start again.

I decided we could retreat no longer. We had to have a broad market presence. We needed at least one profitable, growing, global brand in every segment—including the low end. That explained why we had to control and sell Swatch ourselves rather than license it or sell it through agents, as some people had proposed. It also meant we had to reinvigorate Tissot, the only global brand we had in the middle segment.”

The “layers” Hayek is referring to regard a visual example he used to illustrate how various watch price points and production volumes together fund the overall watch industry. The largest layer on the bottom is the lowest price point, and each layer going up is higher price points, but lower volume. In the early 1980s, Switzerland produced the majority of “expensive” watches, but such high-end watches only accounted for 3% of the overall watch market. This means Switzerland was selling very few watches.

Hayek’s plan was simple, and that was to penetrate the lower-price points with attractive models and brands such as Swatch. Since Hayek’s death, we’ve see the Swiss watch industry move further and further away from truly accessible price points for most consumers. Hayek’s plan was to have good watches at all price points, and yet the Swiss watch industry today in large part has reverted to only selling very high-end watches.

Hayek himself warned that without a stable base of high-volume production watches at reasonable prices the Swiss watch market would be left in an extremely vulnerable position. Accordingly, as Hayek saw and further predicted, non-Swiss watches have crept in to take up most all of the lower-price point positions – namely Hayek’s old nemeses in Japan as well as China. Hayek was fiercely against the popular idea (at the time in the ’80s) of selling to the Japanese as he felt a Swiss watch would only be Swiss if it was owned and operated in Switzerland.

Today we see a lot of Hayek’s fears unfolding as Swiss watches are mostly attractive only in the higher price points. Hayek would suggest that brands once again focus on high-quality Swiss made timepieces at all levels.

“The banks studied our report and got nervous, especially about Swatch. Some of them worried that Swatch would cannibalize Tissot. Others were more emphatic: “This is not what consumers think of when they think of Switzerland. What the hell are you going to do with this piece of plastic against Japan and Hong Kong?” But we were adamant: if we did not have mass production, if we did not have a strong position in the low end, we could not control quality and costs in the other segments.”

Hayek was not without his detractors. In fact, Hayek had some real opponents who didn’t approve of his ideas. Of course, this is natural. Mass production was very important to Hayek even though it appeared threatening to others who felt the Swiss way was the slow and steady way. Even to this day Swatch (as a brand) more or less has zero competition within Switzerland – which I find to be a curious fact given how profitable it proved to be.

The question is what would Hayek have Switzerland build today in an economy that values cheap quartz watches less than it did 25 years ago. Today people still want to look good, but they also want modern things such as smartwatches. Would Nicolas Hayek be into smartwatches? I think that all evidence points to “absolutely.”

Hayek was involved in tons of high-tech experiments (especially in the 1990s) with the Tissot T-Touch being among the most impressive. In 1993 Swatch released the Swatch Pager Watch, which was exactly as it sounded. You can bet your gold Omega that Hayek Sr. would have invested heavily into smartwatches in one way or another.

“I understood that we were not just selling a consumer product, or even a branded product. We were selling an emotional product. You wear a watch on your wrist, right against your skin. You have it there for 12 hours a day, maybe 24 hours a day. It can be an important part of your self-image. It doesn’t have to be a commodity. It shouldn’t be a commodity. I knew that if we could add genuine emotion to the product, and attack the low end with a strong message, we could succeed.

We are not just offering people a style. We are offering them a message. This is an absolutely critical point. Fashion is about image. Emotional products are about message—a strong, exciting, distinct, authentic message that tells people who you are and why you do what you do. There are many elements that make up the Swatch message. High quality. Low cost. Provocative. Joy of life. But the most important element of the Swatch message is the hardest for others to copy. Ultimately, we not just offering watches. We are offering our personal culture.“

I found these statements by Nicolas Hayek about his philosophy behind design and marketing very relevant and wise. He understood before anyone in the modern era the appeal of a “nice” watch. It isn’t about feeling rich or wearing history, it’s about feeling and looking good. Hayek was intimately involved with product decisions as well as pretty much all marketing decisions. These were his two obsessions and he focused on them daily not because he wanted to but also because he needed to. Why? Because no one else seemed to understand the simple formula for what makes a good watch like he did. He imparted much of this knowledge to others who worked with him, but none understood it quite as well as Hayek.

What I think is important here is that Hayek’s suggestions aren’t just about a brand or product, but also about marketing. We live in a time when the majority of watch marketing isn’t good, mostly because no one really seems to care about it or seriously invest in it.

Hayek says that with a watch “we are offering them (the consumer) a message.” This message needed to be formed and also communicated – something that the watch industry today fails far too often to do. Hayek also says that watches offer “personal culture.” This has been correctly implemented in the past, so why is it so incorrectly implemented today? Again, the answer goes back to the idea that no one at the brands is truly invested in the success of marketing, and no one quite understands the particular formula like Hayek seemed to. I’ve said for the longest time that the watch industry as a whole needs to start seriously investing in marketing creation, as well as to foster an open-minded culture about it. Hayek himself was more than familiar with the conservative approaches taken by the Swiss. So what he did was simply to bypass the decision making process and hand out orders. It might sound a little autocratic (and it was), but it worked pretty well.