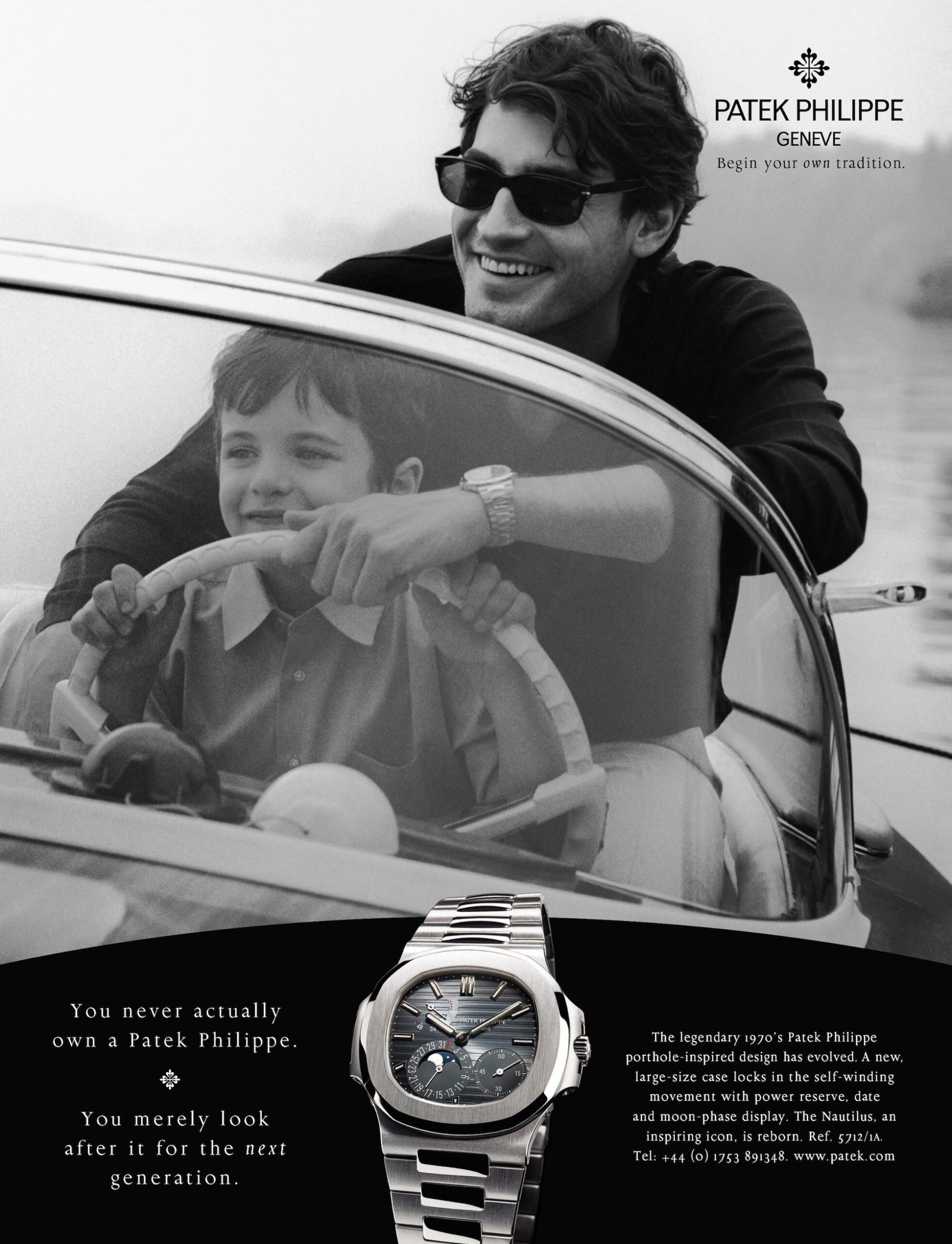

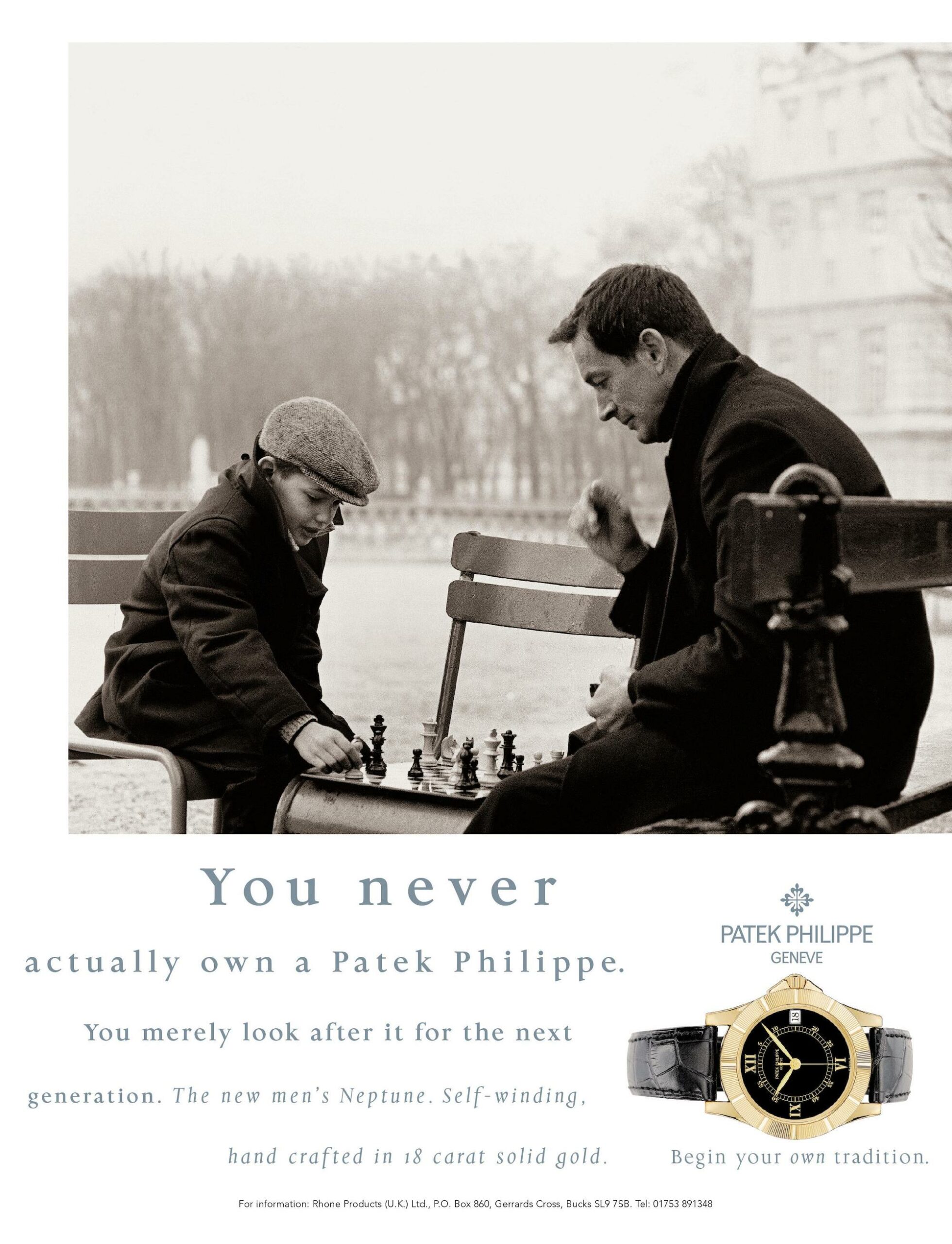

In 1996, Patek Philippe introduced a new campaign that read “You Never Actually Own A Patek Philippe, You Merely Look After It For The Next Generation.” The watch industry and some of its marketing and sales practices have triggered me a number of times over the last decade, but this particular ad, I distinctly remember, was the first that irked me, long before I entered the industry. Strangely, today, it rhymes with a greater issue in watch design, watch buying, and watch collecting and so, instead of a neurotic outburst on condescension in Swiss luxury watch brand marketing, let me tell you why you keep buying the wrong watch.

First, a brief on that campaign, because it is a rarely discussed, yet influential component of modern luxury watch history. Patek Philippe seemed to have wisely recognized early on that the post-quartz crisis luxury watch market was brimming with wealthy customers looking to buy their first expensive mechanical watch, either in decades or, indeed, ever. Many of these customers, they realized, were insecure because they had been exposed to very little in-depth watch knowledge and analysis. Importantly, forums, blogs, vlogs, for they had not yet been invented, were not on hand to provide independent and verifiable answers to a novice customer’s questions. Therefore, marketing and brand image could make an all the more effective impact.

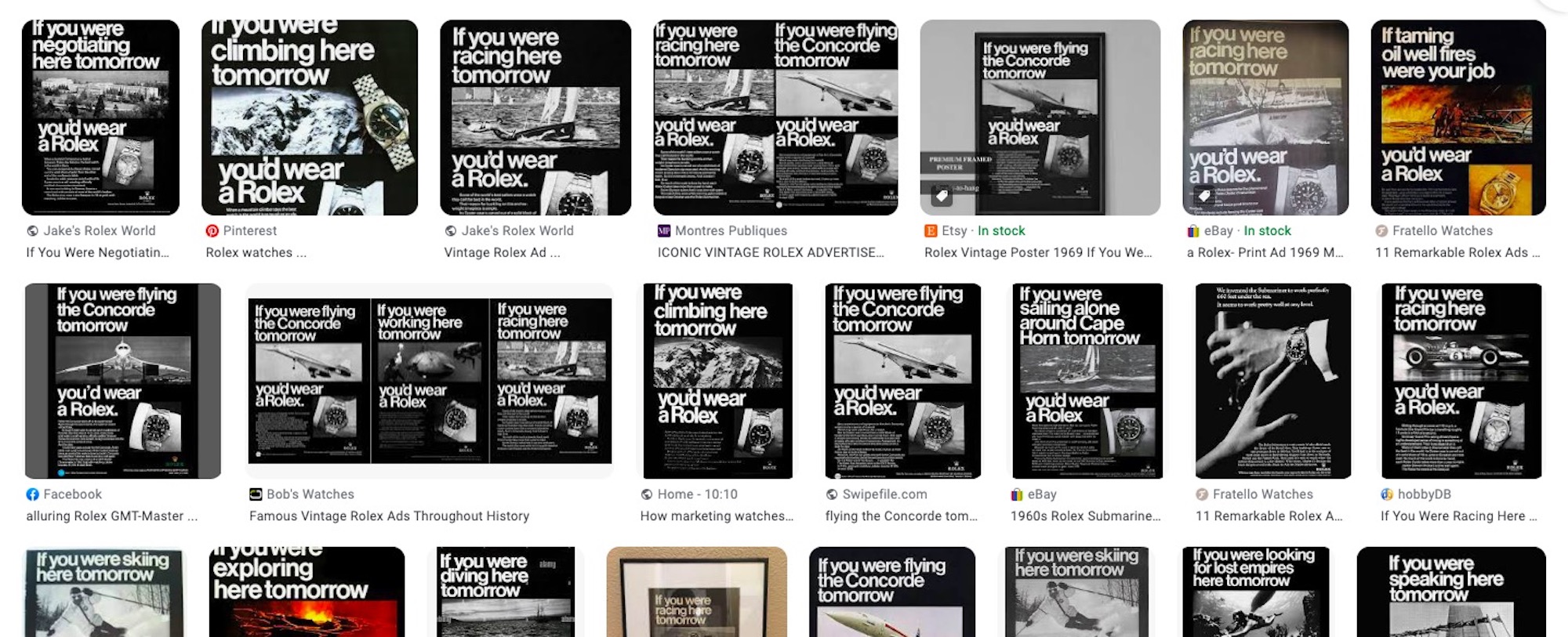

Well aware, some brands had this hunch that they should imply that it isn’t their watch that should grow up to being worthy of the customer — instead, it is the customer that should want to feel worthy of owning said product. It wasn’t just Patek Philippe with that opening line. Rolex famously ran its “If You Were…” followed by lofty statements, as in if you were negotiating in Geneva’s Palais des Nations, taming oil well fires, racing the fastest sailboats in regattas, then you would wear a Rolex. Mind you, all those are actual examples. Never mind that the majority of Rolex customers have by all probability been hard-working folks with more or less perfectly normal lives given that incomparably more of the well-heeled white- and blue collar workers are buying Rolex watches than do diplomats, oil rig firemen, regatta racers, or vulcanologists. Thankfully, this tactic on luxury watch marketing has been recalibrated over the years, but how and why that happened we’ll discuss at another time because we have a more important matter on our hands today.

Although the “You Never Actually Own A Patek Philippe” tagline is still with us, strangely, and if I may say, sadly, we have seen an ever-growing group of customers follow it almost literally, from the moment of choosing their next purchase to the second they sell it.

Here’s the rhyme. Although the “You Never Actually Own A Patek Philippe” tagline is still with us, strangely, and if I may say, sadly, we have seen an ever-growing group of customers follow it almost literally, from the moment of contemplating their next purchase to the second they sell it. It’s in the comments sections all over the horological corner of the Web, in the private emails and direct messages that we receive, and in the stories boutique sales staff tell us. As it stands, a staggeringly high portion of the current luxury watch buyer base out there refuses to buy a watch they are not absolutely sure will have strong appeal on the used watch market. In other words, folks today want to buy the specification that will appeal not just to them, and maybe some others, but to a vast pool of potential subsequent owners — to somebody they don’t know or care about — and yet the watch is supposed to be guaranteed to tickle an unknown customer’s fancy so that its resale probability and value are high. A strange twist to this story, let’s not forget, is that the watch we are often talking about is yet to be purchased by the first owner.

You don’t need to turn the wheels of time back too much to recall how used luxury watches used to be priced like other used items normally are — at a severe discount from their original purchase price. Since then, it happened that not just a few obscure, difficult-to-identify, highly collectible references, but almost every single model of the biggest brand in the industry, Rolex, can be used and then sold for their original cost, and often many times over that. The same, albeit over much smaller quantities, has happened with Audemars Piguet, Patek Philippe, and Richard Mille watches, a phenomenon highlighted by ongoing coverage by the general media. The remarkable attention the sky-high resale values of these watches received has severely distorted the public’s views and expectations on the resale value of, well, basically all other luxury watches.

Not everyone wants a Rolex, but not everyone is happy with buying something else that will lose them a bunch of money over a period of just a short few years. And so the game has begun, hunting for the next best brands for resale, and then narrowing the selection of these few companies down to those few collections, models, features, case sizes, and color palettes, even, that will outperform the rest of the lineup. When we say “outperform,” we don’t mean wearing appeal, horological values, or greater ownership experience, but specifically resale.

Make no mistake, I appreciate that everyone in their right mind would take their best chance to have as high a return on such an expensive purchase as a new watch. That said, based on all the private inquiries and public comments that I have been seeing and sales staff testimonies I have been listening to for years now, it feels like there is arguably too much an emphasis on residual value and what I’ll call “residual appeal” and too little on other factors. So let’s dissect this a little bit and see how it could be changed so that your next watch purchase is more enjoyable — to you.

We’ll begin with the most important point, something that is more than blatantly obvious, it is hurtfully cliché, but we’ll give it a horological twist, so bear with us. Life is too short for generic watches. We specifically didn’t say “boring watches,” because sometimes all we need is a straightforward, restrained, modest, simple watch that many would ill-advisedly label as boring. The issue today is with generic watches. What’s generic? Something that looks a lot like the next thing, that is replaceable to the extent that if someone swapped your watch on your bedside table for one of the many alternatives, you’d receive virtually identical visual elements, design choices, features, materials, and overall wearing experience.

These are 9 different Rolex collections, four from the Classic and five from the Professional lineup. Collage from pre-Watches & Wonders 2023.

The number of interchangeable watches has risen shockingly high. Part of the reason is that brands saw Rolex build a modular collection with lots of interchangeable parts and designs — and people can’t get enough of it. All it takes is some dedicated Googling or sourcing a few watch magazines to see how fantastically diverse and indeed complex watch case and bracelet design used to be in the 1990s and 2000s — and that, in some ways, holds true for Rolex, Omega, TAG Heuer, and other big players, too. Many of those creatively styled and engineered watches are celebrated in our No Longer Made series of articles.

Another reason behind this cookie-cutter design is the exponentially growing gravity field of certain watch types — and can you guess which watch styles those are? The ones with the best resale properties. Rolex arguably started it all with its lightly varied lineup of watches and others in growing numbers have followed suit in recent years, trying their best shot at forcing the steel-bracelet-steel-case magic recipe upon their existing product portfolio. Sure, many have offered watches on a steel bracelet before, but big-brand priorities have definitely shifted to add, refresh, or revive watches with this setup much more than others.

The result? We are invited to express ourselves within the strict constraints of this canvas. Isn’t it ridiculous to suggest that a dial design change or perhaps the addition of a date or some tiny crown guards can justify entirely new collections? Well, that’s what we are looking at now because we’d rather accept a slightly different take on a recipe that’s proven its mass appeal over choosing something more outlandish and personal that we might feel left alone with. Social media, as well as the aforementioned exponential effect, has intensified the focus on the appeal of a select few watch styles, and the greater the recognition of these becomes, the smaller the fanfare will appear around the rest.

It’s a naive statement, sure, but watches are supposed to be fun — and fun is very rarely universal.

But if we are chasing mass appeal so desperately, do we actually take ownership of our watches? Or was Patek Philippe right, in a way, and are we simply looking after them for the next person? It’s a naive statement, sure, but watches are supposed to be fun, and be fun across the board — fun is very rarely universal. Every single one of the 15,780,449 watches the Swiss have exported in 2022, the tens and hundreds of millions produced in Asia, and the handful that were made in Germany, the USA, and elsewhere in the world — all of them should be fun rather than bland, if you ask me. Sure, aspiring Forex-hobbyists can start treating items of our beloved passion as assets, buying and selling watches they might not even want to take delivery of, just have them stay with the dealer or be dropped at a guarded facility, betting on their short-term market performance. But they get to do that because certain modern watches have become as generic and boring as the common stocks of a multinational company.

Are we after the right watches if they have become so generic and boring that they got turned into a mass of tradable assets?

Here’s the twist, though. We can blame luxury watch scalpers for spoiling the fun for us as they reserve a lot of the inventory to fuel their money-making machine, while watch enthusiasts out here in the wild claim they are longing after wearing and cherishing these products. But are we after the right watches if this is what’s standing between us and our next purchase? If certain watches have become so unapologetically generic and boring that they got turned into a mass of tradable assets, shouldn’t we, watch enthusiasts, be steering clear of them and supporting those brands with a passion for horological creativity and boldness? Maybe we should. Or maybe it’s just that we all actually like the same thing.

In closing, a final question to you: If you own a watch, whichever it may be, and the time comes for you to sell it, how many buyers do you truly need? Just one. All you need is just one other person with your taste, out there somewhere, to pay a fair amount for your used timepiece. So, then, why do so many of us appear to be after watches that hundreds, thousands, or even hundreds of thousands in the world can recognize? Could it be that we are seeking not just strong resale but also the recognition of others while our ownership lasts?

I’m curious to read your answers and thoughts in the comments below, but until then, I’ll close this column on a personal note. I refuse Patek Philippe’s idea, however poetic or lofty it may be, that I don’t actually own a watch I paid a chunk of my taxed income for. I look after it only because I like it and respect the work that was put into it — and not because somebody else after me will come to continue the great tradition of not actually owning it. All we can do is encourage you to buy something with a value that is within your comfort zone and that you find attractive. If the value is there and you find it to be fun, by every chance there will be others out there who’ll find value in the same thing as you did.