It was during Baselworld 2008 that Swatch Group Chairman Nicolas Hayek, Sr. unveiled the reference 1160 pocket watch – an impressive ode to what is probably the world’s most valuable and celebrated timepiece. The 1160 pocket watch was made as a replica of the original 160 pocket watch produced by Breguet in the 18th and 19th century, originally ordered for Marie Antoinette in 1783 (lots more background information in the above-linked articles). The Breguet 160 was to be the most complicated pocket watch ever made and it required over 40 years to complete because of not only the French Revolution but also due to factors such as Marie Antoinette being executed and the passing of Abraham-Louis Breguet.

In 1827, the next generation of Breguet watchmakers completed the reference 160 pocket watch. It remained at the firm’s office in Paris and was later sold and resold a few times to collectors. Eventually, it was purchased in London by Breguet collector Sir David Solomon in 1917, who later took it, and other Breguet timepieces, with him to what was then Palestine (which was under British control until it became the country of Israel). Solomon’s daughter constructed a museum in Jerusalem when Solomon’s Islamic art and Breguet timepiece collection were stored – including the reference 160 pocket watch. In 1983, the reference 160 and other Breguet timepieces were stolen.

Completely out of coincidence, the reference 160 and the other treasures were rediscovered in 2008, mere months after the 1160 was unveiled. The irony, of course, is that the Swatch Group invested three years developing the 1160 pocket watch without ever actually seeing the original 160. Watchmakers and engineers at Breguet merely had some incomplete photography and a lot of text descriptions and some illustrations of the 160 timepiece. The information proved to be enough to create the 1160, but Breguet’s watchmakers shared with me that in some instances they had to guess how particular complications in the movement were originally constructed.

Imagine the feeling of the team that produced the 1160 from pictures and guesswork when the original 160 pocket watch was discovered just months after its unveiling. Perhaps it was Mr. Hayek himself was who the most surprised. The investment in the 1160 replica was to “complete” the Breguet brand so that consumers today could enjoy a complete experience. That said, it is unlikely that even the millions of dollars it cost to produce the replica would have been enough for the Swatch Group to purchase the original outright. We can only guess, as such a situation has not yet come to pass.

The presentation box that was produced to house the Breguet 1160 has its own story and sentiments behind it. The beautiful wood marquetry box has a few hidden pushers to release the stop, as well as the pocket watch compartment. Its design, however, is not the most important feature, but rather the wood used to make the box. That wood comes from a particular oak tree in France known to be a favorite of Marie Antoinette. In 1999, a large storm in Versailles toppled the tree, located near the Chateau Trianon, which is a smaller structure that Marie Antoinette resided in on the larger Chateau Versailles palace grounds.

The tree was purchased by the Swatch Group at an especially high price in order to donate money for the restoration of rooms at Chateau Trianon, where select visitors today can better see how Marie Antoinette and her staff lived. The stump of the oak tree remains on the Versailles grounds, while the rest is owned by Breguet. It is unclear what they have in mind to do with the rest of the oak, and I don’t think Breguet is in a rush given lots of future opportunities to keep celebrating the company’s historic clients, such as Marie-Antoinette.

The history of the Breguet reference 160 and the 1160 replica are endlessly fascinating unto themselves, but an entirely different story awaits those who are curious about the construction and complications of the large pocket watch. According to Breguet’s team today, the 160 itself was really an accumulation of the many complications the firm had been mastering for a while, all elegantly combined together in one complex package. This is important to consider because it means the 160 was really a testament to the best which Breguet was then known for, not an experimental item like the many which Abraham-Louis Breguet himself developed during his lifetime as he sought to master accuracy and reliability in chronometry.

This article marks the third time I have written a lengthy piece about the Breguet reference 1160 — and each time I learned more and more about the story about both the original and the replica. I linked to those articles above, but the first time was in 2008 when the Swatch Group first unveiled the Breguet 1160 pocket watch, and the second was in 2015 after being able to examine the pocket watch at a Breguet exhibit in Europe. In 2019, while traveling with Breguet to Paris and later to the brand’s headquarters in Switzerland, I finally got a chance to experience the 1160 pocket watch for myself. This article was actually started at that time and later completed in the second half of 2021. That means that my relationship with this particular timepiece — a replica of the world’s most valuable historic timepiece — has been going on nearly as long as I have operated aBlogtoWatch.

View this post on Instagram

Now let’s talk technical. Some of the more noteworthy complications in the 160 and 1160 are an automatic winding system especially developed for a pocket watch (useful but extremely rare), a tourbillon (of course, since it was invented by Breguet), and a dead-beat seconds hand (in addition to a traditionally running seconds hand) that allowed the user to easily count or measure seconds. Other complications included a sophisticated calendar and a thermometer (which was important because, at the time, timepieces were much more temperature-sensitive, and the ability to read the temperature was of great interest to the user).

Given that Breguet was in no rush to complete the original 160 (Marie Antoinette was beheaded about 10 years into the construction of it), the piece became a playground for the company to install its latest achievements or experiment with something new. The original prompt when it was commissioned by Count Axel de Ferson for Marie Antoinette (he was into her) was for Breguet to produce the greatest timekeeping mechanism the world had ever seen. For that reason, watchmakers applied both complexity and practicality to the reference 160. It indicated the time, visually and via sound, by way of a minute repeater. It let you know both the time of day and the time of year, along with other astronomical complications that had implications on daily, industrial, or navigational life. The watch also contained ways of determining how accurate it might be, as well as ways to improve accuracy, such as a tourbillon. It also featured an automatic winding mechanism so that you didn’t have to bother with winding it as much. And, after all of that, you could use it to measure how long it took your carriage to travel a mile and thus get some idea of when you might reach your destination. We find romantic the notion of historical treasures like the Breguet 160 and cherish them as almost priceless. Yet, at the end of the day, these are tools intended to improve our existence, not just our status.

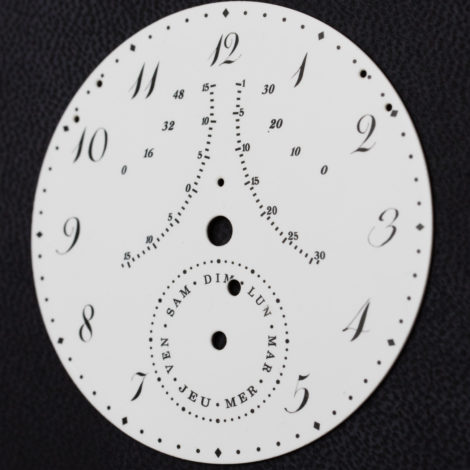

The Breguet 1160 Marie-Antoinette comes with two dials – as the original seemed to. One dial is a traditional enamel dial, and the other is a transparent piece of rock crystal with indexes painted on it. This means it was considered valuable, or at least fashionable, to display the clockwork mechanism in the movement back in Abraham-Louis’ time as much as it is in fashion today. It makes me smile to consider that 200 years ago, watch lovers probably displayed a similar look of wonder on their faces as we do today when we see the mechanical dance of a timepiece movement. Rock crystal might seem like an odd choice until you consider what materials they had available in the late 18th century. Rock crystal could be milled and polished. Glass had to be blown and was probably a lot more fragile. Thicker glass probably caused visual distortions when trying to see small, precise details on the dial. Like the original 160, the 1160 uses a polished rock crystal over the dial and caseback. And yes, this massive 63mm-wide 18k-gold pocket watch is rather heavy, but in a really assuring way. The original reference 160’s movement was produced from 823 parts, but I am not sure if it is the same for the replica (though the parts are likely to be very close).

Handling the 1160 is nearly as impressive as gazing into it. What I think originally attracted me to the story about the Breguet 1160 in 2008 was that nothing I have seen, before or since, looked anything like the dial and clockwork of the Marie Antoinette pocket watch. And that is really surprising in the watch industry because “emulation” (copying) of the past is a built-in part of how things operate. While there certainly are a lot of other pocket watches and watch movements with similar parts and sections, nothing else ever made seems to capture the geometric interest and opulent grandeur of all hand-made and hand-polished metal parts. The dial has so many layers, and it’s intimidating to even imagine a drawn schematic of how it is all put together, let alone how it works. In other words, I’ve seen an awful lot of new and old timepieces in my day, and nothing impresses or wows me as much as the Breguet reference 160/1160.

The Breguet reference 1160 was developed by the late Nicolas G. Hayek, the chairman of the Swatch Group until his death in 2011. That makes the 1160 one of his last major feats. He began development of the 1160 explicitly because the 160 was not available and because he felt that Breguet, as a brand, was not complete without it. It was sort of a marketing thing and sort of a pride thing, for him, in my opinion. It must have also been a shock to Mr. Hayek when just months after the 1160 was debuted at Baselworld, the original 160 was rediscovered.

One of my biggest regrets is that I was not able to speak to Mr. Hayek, Sr. during his lifetime about the Breguet Marie-Antoinette pocket watch project and the brand, in general. Today, his grandson Marc Hayek acts as the president of the brand, and perhaps in the future, I will be granted an opportunity to discuss both references with him. Just a few years ago, I would have been convinced that the original Breguet 160 Marie Antoinette would have enjoyed a permanent home back at the L.A. Mayer Museum in Jerusalem (where it was prior to being stolen in 1983, and later recovered less than a two-hour drive away a few decades later). Today, I am not so sure, and I believe a possibility exists that the Breguet 160 will not remain in a museum or might be purchased by a different museum.

The problem is the issue of the Breguet 160’s potential value. In around 2013, a rough estimate had priced that Breguet reference 160 at about $30 million. In the last decade, the high-end auction market for precious timepieces has increased many times over. The greater interest in watches, as well as the accompanying funds, means that it is not inconceivable for the Breguet reference 160 to be valued at over $100 million as an entirely seminal, unique item in the timepiece collector universe, as well as a testament to human mechanical achievement. It is also true that the watch collector market (like many others) could have ebbs and flows that will see watch values waning over time away from the incredible highs of today.

Faced with the prospect that an incredibly valuable asset might experience a decrease in current merchantability, an owner of that asset might very well want to cash in on it when the market is still hot. There will also never be another item like the Breguet 160, and no expert in the field seems to argue that the piece is any less important or impactful than it has been historically. Let me remind you that it took between 1783 and 1827 to build it and that it was the world’s most complicated timepiece for nearly 100 years. Now that I’ve been privileged enough to handle the Breguet 1160 pocket watch, the next logical step is to chase down the original 160 Marie Antoinette. You can visit the Breguet watches website here.