In recent feature articles and Spending Time podcast episodes we have addressed the rather more serious issue of suppressed creativity in the watch industry, along with the economics behind this trend – here I tried to explain the problem in a nutshell. Add to this the fact that numerous creative people at big brands and groups have been literally silenced by their employers, as they have been banned from giving interviews or even responding to external emails. Yes, this has been an escalating thing in recent years. With this in mind, or even disregarding all that nonsense, you can imagine – and hopefully share – my relief-mixed excitement in getting to meet Konstantin Chaykin, one of the most creative and gifted watchmakers of our time, who, mind you, is also totally independent. I visited him on his home turf, inside his two-story manufacture building in the Nagatinsky Zaton District of Moscow.

https://www.instagram.com/p/Bn3iIXQH4Ny/?taken-by=ablogtowatch

Come to think of it, I’ll say that perhaps one of the least talked-about aspects of watchmaking is the creative process. Nobody ever talks about it much in a meaningful way and, as I realized while preparing my questions to ask Konstantin, that’s due only in part to that self-imposed quarantine I mentioned above and is also largely thanks to the matter’s hard-to-grasp nature. The easy-to-understand part of the matter is the rather natural order of tasks into which the creative process can be broken down: it begins with a source of inspiration or idea, followed by a lot of sketching and drawing to put said inspiration or idea into shape, then narrowing things down to a few – preferably one – concept that is then to be carried through the painstaking process of fine-tuning, finalizing, production planning, prototyping, more fine-tuning, more prototyping, test production, more fine-tuning, and then the actual production process itself… Oh, and, last, it’s best not to forget to try and bring the finished product to the market with a bang.

But it all begins with an idea and it’s this idea and the materialization of said idea that is so scarcely discussed and that is so difficult to understand for us, outsiders. We all know that an idea can come out of the blue, or, rather more often, from a source of inspiration that, in turn, is linked to personal interests and fascinations… But there’s so much more to it than that.

Following a nerve-racking 80-minute taxi drive through Moscow – the trill of a lifetime, I can tell you that! – I arrived at the Konstantin Chaykin manufacture. Because what’s a better combination for a festival of fiery plastic death than cheap petrol, poorly maintained cars, lots of traffic, and the deep-rooted spirit of racing for the same patch of tarmac evidently shared by thousands of Eastern-block taxi drivers?! Set in the bowels of a decidedly Russian industrial estate, the Konstantin Chaykin manufacture building itself is actually neat, with little flowers and Konstantin’s red Ducati bike surrounding it. After passing a few watchmakers who were enjoying a quick break, getting a breath of fresh air (and nicotine), before the Napoleon- and Hitler-defeating Russian winter would rear its unfriendly head again, I entered through multiple security doors, climbed a flight of stairs and finally arrived at a matrix of offices at the end of a hallway. The first room I entered was that of Konstantin’s super kind secretary, whose office walls are decorated by some 73 framed documents hanging on them – these are the pending patents awarded for Konstantin’s inventions. In fact, there are so many of them that the walls have actually filled up and now the frames continue down the aforementioned hallway. Click on the middle of the frame below to start a quick video view of this room.

https://www.instagram.com/p/Bn3KblMHbXM/?taken-by=ablogtowatch

Given that I arrived at a time when he was temporarily away for meetings, I waited in Konstantin’s office where I had a chance to be shown around and take a bit more time for a better look at where he runs his operation, brand, and creative efforts. I was overwhelmed by the cumulative effect of the following: some massive, colorful oil paintings (all horology-themed, of course) hanging from the wall, a painter’s stand with Konstantin’s drawing on it of his upcoming Mars Conqueror watch (that will be debuted a couple of months from now but its movement was introduced here), a long arrangement of bookshelves that I’ll come back to in a minute, a watchmaker’s bench near the window at the far end of the room with a random assortment of vintage movements, watch parts, and a surprising amount of camera gear. The latter makes sense as Konstantin produces most all of the photography and videography that gets published on the manufacture’s Instagram page.

On his desk, beyond the usual computer gadgetry, I saw an assortment of loupes along with a special desk lamp that provides crisp, even, neutral light for checking prototype and working pieces that come in from other departments for him to quickly check. There is no shortage of nerd-fest toys and gadgets either. There is a large Mars globe that is spinning on a weird stand without any indication on how it actually works, there are space shuttle and rocket models, the Russian army’s monthly supply of coffee capsules, and Ferrero Rocher sweets, and a ton of stuff laying around enforcing the rule that the genius can see through the chaos. Behind his office desk is a cabinet with a number of his old table clocks.

Konstantin arrives and, like everyone I’ve ever met who actively runs a successful organization, he too is ready to cut to the chase – but only after a quick, friendly inquiry if my travels were alright. I say “Yes, of course!” – I mean, I made it after all! Having done my homework – and more so having been a long-time fan of his work – I understand that I’m speaking to a watchmaker who’s produced some of the most creative and versatile ranges of work in recent memory. This includes, but is not limited to: a watch with a mechanical cinema with the sound and visual effects of the first ever recorded motion picture; a watch with a mysterious time display that, let’s be kind, possibly inspired Cartier to do their Mysterious Hour watches; special one-hand watches that display both hours and minutes; the crazy Lunokhod; the incredibly successful Joker (selling for over double retail online); this insane Computus Easter Clock; the upcoming Martian watch; the Quartime “6 by 4” time of day indication dress watch (hands-on coming up later); plus a range of one-of-a-kind, ultra-complicated pieces that he has produced on special orders but not marketed. Just dwell on any one of these for a second to appreciate their mechanical complexity and novelty factor, before trying to imagine the level of creativity and zest required to conceive, design, and produce a line-up of mechanical watches of such variety.

Konstantin, with a tray of highly complicated prototypes in front, and just some of his books behind him.

This makes for a track record that is important to identify if we want to better understand his work and his place (or lack thereof) in the watch industry: Konstantin is utterly disinterested in traditional complications. To illustrate the extent of this, and perhaps also a bit to testify to his abilities, he pulls out two trays from a lower shelf of a small vitrine, set aside in the corner of the room, blocked by the painting stand and other stuff he clearly deems more important. These two trays had over a dozen different prototype movements on them and so I take one out and he says, with not much effort to cover up his boredom, “Yes, that’s a tourbillon prototype.” I guess that’s a “Yawn,” then. Next to it is one with something that looks like a fusée and chain – evoking the same reaction from him. Out of courtesy he of course shares a few details of these movements but, rather elegantly, gets sidetracked as he picks up and starts talking about the module he designed and made for the Genius Temporis – the single-hand watch whose hand flicks from indicating the hours to indicating the minutes on demand, with the press of a button.

This really begs the question: what’s the creative process behind all this actually like? How are those previously mentioned watches with those totally unique and rather quirky – albeit magnificently executed – complications conceived? I don’t even want to bring actual execution and production processes into the equation (yet), as this matter is already complicated and novel enough all on its own.

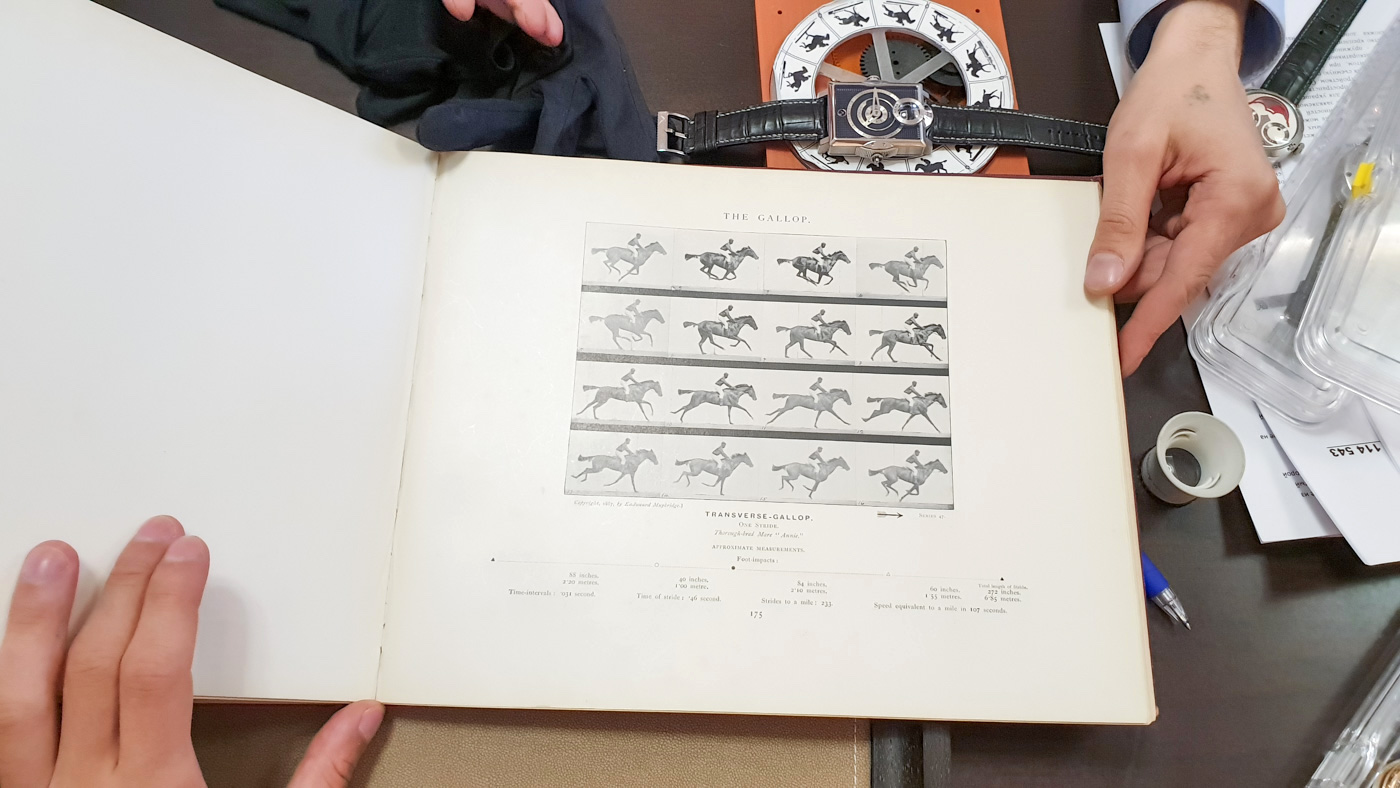

An over 100-year-old copy of Eadweard Muybridge’s Animals in Motion, the source of inspiration and technical reference for Konstantin’s Cinema motion picture watch.

The root, I found, that feeds these ideas is set in Konstantin’s extremely wide scope of interests, as well as literacy in not only fine mechanics, but so much more. This leads me back to that bookshelf I mentioned I’d say a few more words about. The first book I pulled from there while waiting for him to arrive was about watch wearing habits through history – and indeed, it explained, through some rather hilarious and/or impressive paintings, how the 1%-ers of several hundred years ago used to rock their special pocket watches. The actual range of topics covered by these books stretched from European Pendulum clocks, Continental and American Skeleton clocks, or haute horlogerie movement finishing techniques through Ferdinand Berthoud’s “Longitude at sea” all the way to rather more obscure publications about Dresden’s Royal Cabinet of Mathematical and Physical Instruments (you follow?) or a 100-year-old copy of Eadweard Muybridge’s Animals in Motion (an immensely fascinating book that I’d recommend checking out). These aren’t for show either: as we went through a box full of his finished prototype or already sold and yet-to-be-delivered pieces, he had no trouble grabbing one book after the other, hitting them up at page number-whatever to show what inspired or helped him through his creative process.

The oldest known clock movement in Russia, dated 1539 – and exhibited at a rather obscure spot, on an upper floor of a museum in Kolomenskoye.

Konstantin shows – and, again, his work testifies to – his shockingly widespread literacy, fueled by his genuine fascination for, well, pretty much anything randomly from the last few thousand years. It’s an immensely fortunate blend of cultural, engineering, historical, and academic knowledge, which explains how he can go from a watch that keeps time on Earth and on Mars to one that plays jazz music to another that has more character and soul (the Joker), than literally any other watch I’ve seen in my 9 years of being a fully dedicated – and rather privileged – watch nerd who’s had the chance to see and wear a lot of watches. On day 2, which unfortunately had to also be my last day in Moscow, we walked a few miles to Kolomenskoye, a former royal estate situated far southeast of the city center of Moscow, on the ancient road leading to the town of Kolomna (hence the name). We came here because inside the gate building that used to lead to the Tsar’s courtyard, called Palaty Polkovnika, there is an obscure exhibition that features the oldest known clock movement in Russia, dated 1539. I felt this was almost a sort of pilgrimage for Konstantin, who has obviously seen this movement many times before – but was clearly excited to see it again and show it to me, as he is understandably awed by this impressive piece of mechanics from an age when you first actually needed to be a blacksmith to make a clock.

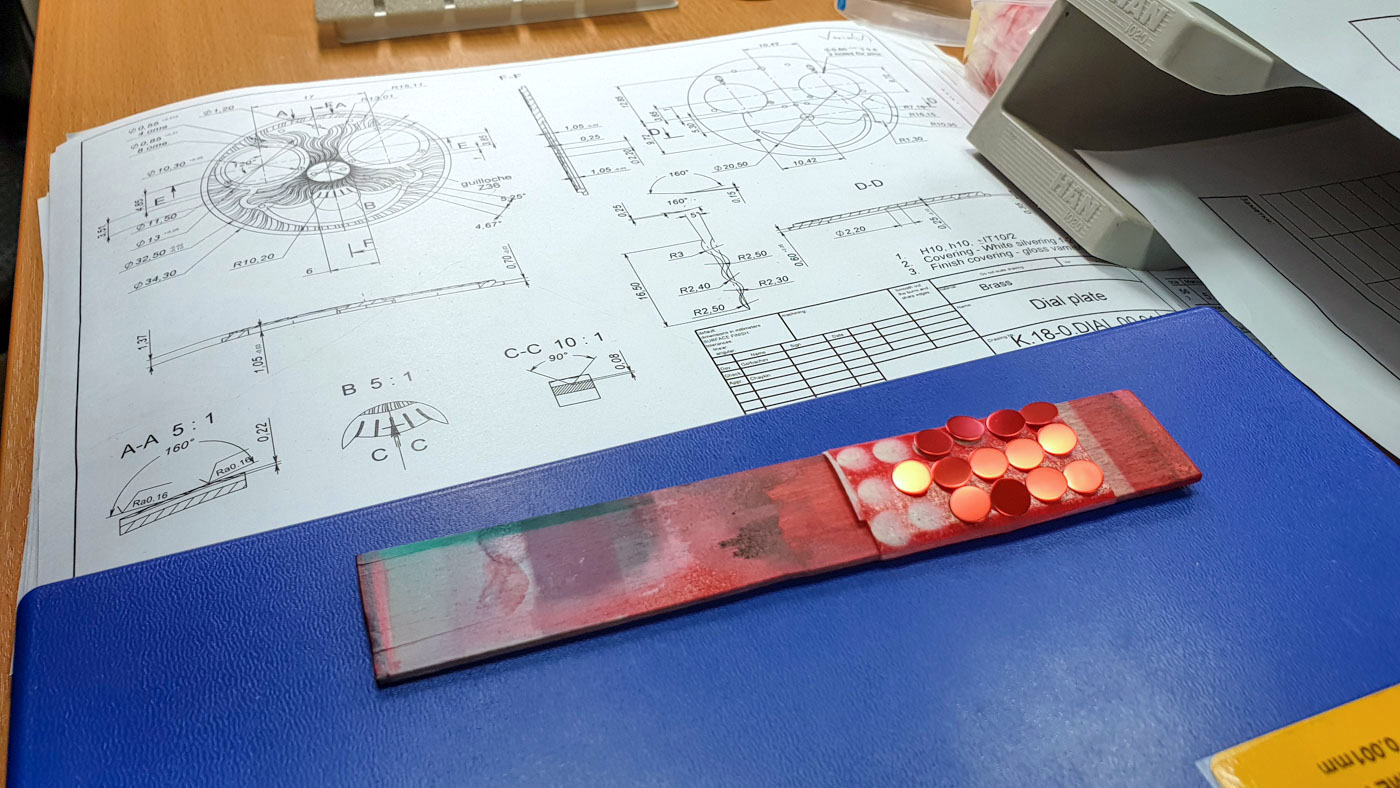

Almost everything is made in-house… Especially since, just an example according to Konstantin, not one German or Swiss specialist dial maker could produce the dial of the Joker and Clown watches to the required tolerances and quality. Even the moon phase discs are hand-painted in a special booth.

It’s Altshuler’s TRIZ system that Konstantin relies on to transfer his ideas into finished watches. TRIZ is a problem-solving, analysis, and forecasting tool derived from the study of patterns of invention in the global patent literature, developed by the Soviet inventor and science-fiction author Genrich Altshuller (1926-1998) and his colleagues, beginning in 1946. In English the name is typically rendered as “the theory of inventive problem solving” that occasionally goes by the English acronym TIPS. I’ll rely on good-ole Wikipedia and share the basic (!) principles of TRIZ here, highlighting the fact that this explanation does in fact make sense when read carefully – even if it scratches only the very surface of an otherwise rather mind-bending technique. In essence, “one of the earliest findings of the massive research on which the theory is based is that the vast majority of problems that require inventive solutions typically reflect a need to overcome a dilemma or a trade-off between two contradictory elements.” If you think about it, watchmaking is drippin’ with such dilemmas and trade-offs. “The central purpose of TRIZ-based analysis is to systematically apply strategies and tools to find superior solutions that overcome the need for a compromise or trade-off between the two elements.”

Sounds too vague? Here’s a bit more detail. “By the early 1970s two decades of research covering hundreds of thousands of patents had confirmed Altshuller’s initial insight about the patterns of inventive solutions and one of the first analytical tools was published in the form of 40 inventive principles. These could account for virtually all those patents that presented truly inventive solutions. Following this approach the ‘Conceptual solution’ can be found by defining the contradiction which needs to be resolved, and systematically considering which of the 40 principles may be applied to provide a specific solution that will overcome the ‘contradiction’ in the problem at hand, enabling a solution that is closer to the ‘ultimate ideal result.'”

Now, all that makes sense not because I’d wish to pretend that I understand any of it, but because I can at least imagine that with the necessary knowledge and practice of this theory, Konstantin can in fact proceed through all the challenging and complicated steps of making watches on his own – and especially watches that are as genuinely unique and novel as those I mentioned above. But it’s also way too easy for us to get lost in all that so let’s get back to something we can get our minds (and hearts) to more easily understand: his first inspired moment.

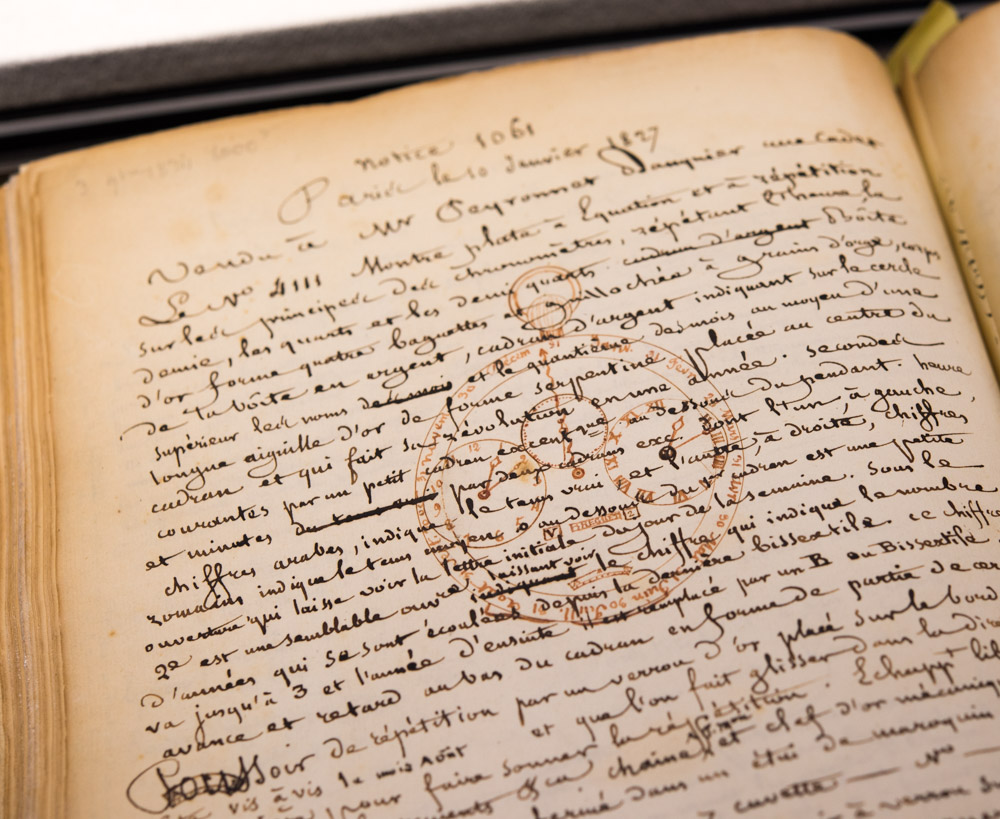

The Breguet Marie Antoinette and a page from Breguet’s original, hand-written archives. Lots to be inspired by, that is certain.

In 2004, Breguet held an exhibition at the Hermitage in St. Petersburg – the city where Konstantin was born. He, then 29 years of age, had been already selling watches and performing basic repairs in a small store that he had owned and was deeply impressed and fascinated by what Breguet could achieve some 200 years ago, without any of the highly precise, modern manufacturing tools that are widely relied upon by watchmakers of today. And so, Konstantin set out to finish his first clock that he started working on in 2003 and finished in 2004, with his rather basic tool set, based on blueprints and guides he could find: a tourbillon… The first tourbillon made in Russia since 1917. It’s fun to realize that some of the very best independents of our time all started out with something outrageously complicated: Hajime Asaoka with his Tourbillon #1, Aaron Becsei with his record-breaking miniature double zappler (quickly followed by a tourbillon travel clock), and Konstantin with his first tourbillon clock. That’s a fun similarity between three of my personal favorite independents that I just recognized.