For a guy who is generally revered by some of the most well-funded watch collectors in the world, Mr. Philippe Dufour is a pretty humble and approachable guy. It isn’t that he doesn’t have an ego – everyone with the ability to admire the fruits of their own work clearly has an understanding of exactly how good they are – but rather that Mr. Dufour is an advocate of hard work and dedication above all else (including how people perceive him). In fact, I would suggest that having a waiting list of orders a few years long and being able to politely say “no” to new requests makes having an ego totally unnecessary. Should Philippe have one of those days where he is questioning himself, no doubt all he needs to do is be reminded that if he lived another 100 years, his work schedule could be easily booked.

What I’ve always personally liked about Philippe Dufour as a man is his straight-forward way of approaching watchmaking. None of the glitz or smoke and mirrors of today’s watch industry even remotely interests him. To say he is a traditionalist would be both correct but also misleading. The term “traditionalist” is often associated with someone stodgy and stuck in their ways – resistant to change and persuasion. That doesn’t characterize Mr. Dufour at all. More accurately, it is safe to say that Philippe is an advocate of hand-finishing timepieces because that is how they become as beautiful as possible. If anything, Mr. Dufour is happy to adapt and adjust as the situation calls for it – but when it comes to his craft, even modern technology hasn’t really given a lot of tools to help that much.

So let’s step back a bit. If you’ve been immersed in the world of fine timepieces long enough, it is only a matter of time before you hear the name “Philippe Dufour.” Most people learn about the name before they ever see any of his products, and a remarkably small number of watch collectors around the world have even seen a Philippe Dufour watch. At the high point of when he employed a few people working for him, the workshop of Philippe Dufour was only able to produce about 18 or so watches per a year. Today in 2015, as I understand, the workshop of Philippe Dufour up in the Vallee de Joux consists of just him. So what is all the fuss about this independent Swiss watchmaker whose name carries with it so much weight and gravitas?

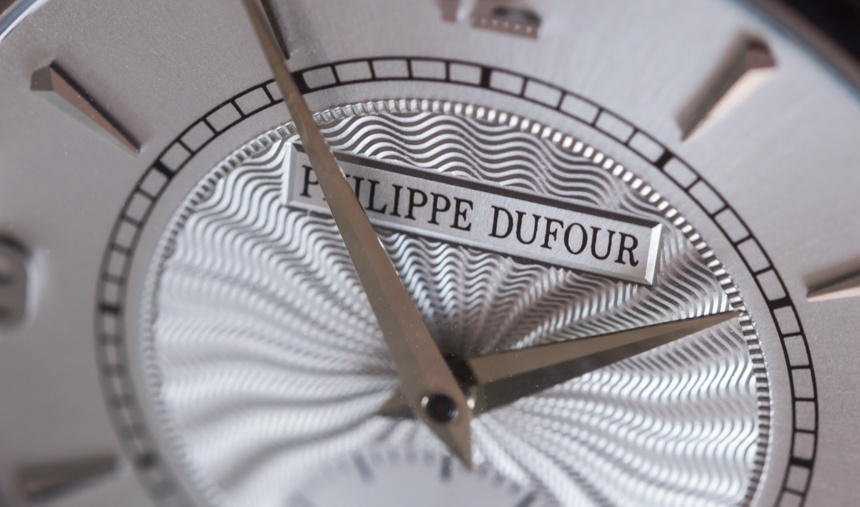

Finishing. That is what Philippe Dufour is best known for. This man polishes metal like few other people alive. And honestly, there aren’t any wild tricks. Philippe Dufour watch movements are so breathtakingly beautiful because the man takes the time and effort necessary to do it. His technique isn’t bad either, and you can’t write off a large amount of natural talent, but Philippe Dufour applies the time and effort necessary to make even his most simple watch movements look their best. He cannot cut corners, he cannot rush the schedule. A Philippe Dufour watch takes time to create because each involves copious amounts of time to finish – and few people are willing to apply the same level of time. It isn’t a marketing gimmick, and there is no velvet curtain strings to pull in order to make a “big reveal.” The allure is in the item itself and the man who produced it. End of story.

Even though I’ve caught Mr. Dufour passing by in his native watch country in Switzerland a few times, I sat down with him most recently far away in Dubai at the first annual Dubai Watch Week. My interest in this chat was to figure out what Mr. Dufour felt was the cause for why so many collectors (especially in the East) hold his work in such high esteem. What I received was a very cogent conversation on some of the most serious deficiencies facing the watch industry today.

Philippe Dufour agrees that he needs a Roger Smith. The late and great British watchmaker George Daniels chose a single apprentice in his life and that was Roger Smith – who continues to produce timepieces by hand on the Isle of Man. Dufour lacks a protege to carry on his work, but that isn’t due to a lack of interest from budding watchmakers around the world.

George Daniels finally chose Roger Smith to become his protege because Smith was one of the only people who impressed him. Perhaps Mr. Dufour doesn’t have as exacting standards – and certainly doesn’t have the reputation for being a difficult man, but he does have high expectations. If you recall, I mentioned that Philippe Dufour once had a workshop with just under half a dozen watchmakers. They are now all gone. Why? Because, according to Dufour, they lacked motivation. Motivation for what exactly? The motivation to make things as perfect as possible.

According to Philippe Dufour, many watchmakers today are lazy and don’t seem to encourage hard work. Very few of them go past their duties and original training and, apparently, are far too complacent. Philippe Dufour isn’t exactly thrilled with the low bar a lot of watchmakers today set for themselves and feels that many of them are far too comfortable with what they are doing. He suggests that I walk into any watchmaking facility in Switzerland and ask people “how long until you retire.” Perhaps a bit of tongue in cheek about it, Philippe claims many of them will know the answer to the day. “They are all waiting to retire.”

One of the reasons Dufour seems to enjoy traveling to Asia is because, according to him, their cultures hold very high respect for maturity and seniority. That he is an accomplished and older watchmaker automatically comes with the impression that he holds great amounts of knowledge – and I tend to agree. I’m not saying that all of our population’s older members are walking around with the answers to life’s biggest questions, but as a society, the West lends few advantages to being a senior. At the very least, Dufour’s advice for younger generations of watchmakers should be considered as very valuable.

Mr. Dufour further seems to feel that today’s watchmaking education curriculum lacks some of the necessary elements that help make great watchmakers. Do you know what Francois-Paul Journe, Peter Speake-Marin, and Philippe Dufour all have in common? Each of them spent time working for auction houses as restorers. According to Philippe Dufour, one of the most pivotal parts of a great watchmaker’s education is just taking watches and clocks and restoring them. This not only teaches people problem solving, but it also teaches them about how a variety of mechanisms work, and how to best understand the ways materials age and how to finish them properly.

So, in addition to not working hard enough, many watchmakers today seem to have insufficient education. This is a powerful lesson for any watchmaker looking to take it to the next level and understand what their business trajectory is going to be. In fact, more specifically, Dufour warns young watchmakers looking to go it alone that in addition to watchmakers and artists, they need to be business people. One of the biggest reasons he hasn’t taken on more people as help today is that he lacks the time to train them – he does need to make watches after all.

“How many watches did you make in the last year?” “About one,” says Philippe, reminding me that he has been working on a Grande Sonnerie – a project that requires about 10 full months of work. When Philippe Dufour created his Grande Sonnerie project, he was extremely excited about it and took the opportunity to learn CAD (computer-aided design). You have to understand that what CAD brought to the world of watchmaking, especially the little guys, is the ability to design something, and then reproduce it. Before CAD drawings and technical schematics, watchmakers would toil to create the piece for just one complicated movement, and after that have to work extremely hard to reproduce those same parts for additional movements. The precise measurements of CAD drawings allow for a machine to reproduce in exact sizes the pieces for each movement so that they can then be finished and assembled. Without computer design, there would probably not be a watch industry today – and if there were, it would be “cottage,” to say the least.