Welcome to Point/Counterpoint, an aBlogtoWatch column where two of our resident horological aficionados duke it out over a point of contention. Last time we asked “Are Vintage Watches Worth It?” and now Ariel Adams and David Bredan spar over the merits of in-house movements.

Welcome to Point/Counterpoint, an aBlogtoWatch column where two of our resident horological aficionados duke it out over a point of contention. Last time we asked “Are Vintage Watches Worth It?” and now Ariel Adams and David Bredan spar over the merits of in-house movements.

Ariel Adams: The economics as well as the psychology of our feelings surrounding mechanical watch movements is often at odds with logic. I propose that quality movements sourced from top-shelf suppliers are, in many instances, as good or much better than those prestigious “in-house movements” we collectors tend to celebrate so often and with such fervor. Consider, first, the notion that watch movements are tiny engines whose performance and reliability are probably the most important things for a prospective owner. For machines to operate well, they need to be thoroughly tested and optimized for performance over (sometimes) years of careful testing and tweaking. Not even computer simulations can adequately test how these machines will operate in the real world.

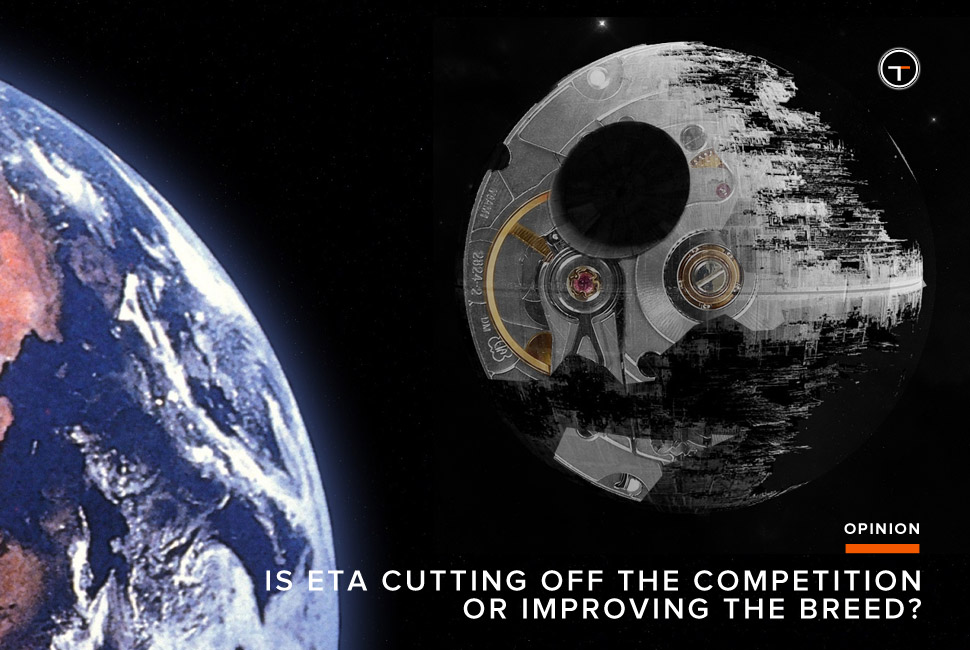

So who, then, has the incentive to do such testing and tweaking? A company who just came out with a new “in-house movement” that will be produced in the thousands, or a company who is in the business of selling movements to other companies and who is deeply invested in the process of making movements in bulk for years? It is easy to admit that watch movements produced in-house by companies certainly have more originality and often decorative value, but aren’t these factors second in importance to having a movement that works well, has been proven to last longer, and can actually be serviced more readily given the availability of parts and skilled repair technicians?

David Bredan: It is an olden but golden saying that there is a first time for everything – and the last fifteen or so years have been the “first time” for in-house watch movements to become increasingly ubiquitous. Major (and minor) watch brands had been getting away for far too long with charging more but giving the same (or less), riding on the high horse of “Swiss Made” – they just forgot to add “Swiss Made (mostly) by someone else.” It would be daft to argue against the importance of the reliability or performance of watch movements, and supporting in-house movements should never come at a cost of sacrificing these fundamental requirements.

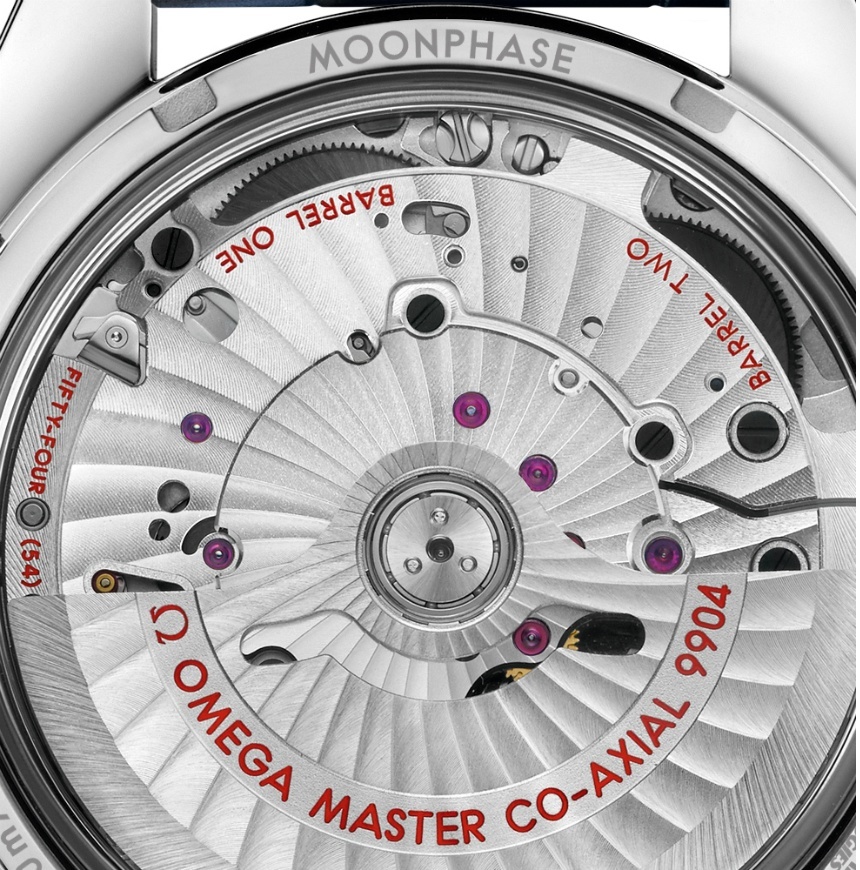

You say that factors such as the originality and decorative value of in-house movements are secondary to other properties such as reliability, durability, and serviceability – and they unquestionably are in the eyes of most. But are these two sets of attributes mutually exclusive when it comes to in-house calibers? Surely not, and while not all manufacture movements deserve praise, there are many simple and more complicated calibers out there that have offered so much more than the supplied base movements they replaced.

This brings me to the point of the utter lack of anything fascinating in owning several of the same base calibers – they may have been designed and developed to last a long time, but many certainly do not want to own more than a few (or just one) of them over the course of years or more of collecting and appreciating timepieces. Getting a different style of a watch but with the same movement is out of the question for many watch lovers because they know they can only get one of a very few base calibers inside. Those looking to appreciate the next great chapter in modern horology (or are simply looking for something new in their next purchase) will want to use and see one of the numerous in-house calibers that function in a considerably more refined way, look more pleasing to the eye, and work better with today’s trends (think of larger case sizes, for example) than the base calibers designed several decades ago that they are now replacing… Even if there is a price premium to be paid.

Last but not least, a few among today’s modern in-house movements may just become the reliable and durable – and yet more refined – base caliber tomorrow.

Ariel Adams: There is no denying the important emotional value of purchasing a timepiece with a movement unique to the manufacturer and perhaps even to the specific watch. The ideal situation for any watch collector is to purchase a timepiece with a movement produced by the company whose name is on the dial. The question, however, is one of economics and value. We both agree that mechanical watches should combine both performance and artistry, but at what price, and how much is the consumer asked to sacrifice? I submit to you that the economics of buying in-house-made movements simply don’t work out in the interest of many consumers as value propositions are all over the place.

In an economy of vertical integration, when a company is responsible for producing its own watches – or anything, for that matter – the rule should be that by producing their own components, they are able to control costs and should be able to charge less money. This is especially true when the performance of a product produced internally is the same as something produced externally and purchased via a supplier. If a movement costs a company $100 to purchase from a supplier, then theoretically, if they produce their own watches (after amortizing the costs of R&D, labor, and machinery), then their per-unit price should be less because they do not need to pay for the profit of a third party company. It is only those companies who absolutely cannot justify the expense of producing their own movements because of low production volumes that should be able to justify the mass purchase of components from third parties. In this classic example, “in-house-made” is a means of controlling costs, offering lower prices, and tangentially offering the consumer something more unique.

With timepieces, this model is oddly skewed as the price of a timepiece with an in-house-made movement – in the vast majority of instances, as related to high-end watches – is higher than for those watches produced with sourced movements. Brands use the more exclusive nature of in-house-made movements to justify increased prices and oftentimes do not deliver increased actual performance – and often only marginal aesthetic enhancements. This is part of a larger culture of offering almost no performance-related data as to the promised operation of a specific timepiece outside of how the movement generally works as a function of basic figures such as balance wheel frequency, power reserve, and little else.

Movements produced from suppliers such as ETA and others in Switzerland have a more or less established track record of performance and a general understanding of their benefits and limitations. Consumers are able to have a more predicable understanding of their value, and based on a number of factors can more accurately sum up the value of a watch as a summation of its case, dial, strap, and movement – along with prestige value. This, in turn, creates a more healthy consumer-controlled price market where value can be part of the equation of buying a mechanical watch. With in-house-made movements, consumers are often asked to trust – often with blind faith – that an in-house movement costs what it does, performs as well or better than more mass-produced, sourced movements, and that the company is there to properly service the movement in the future.

My argument is not at all against in-house movements, as there are some wonderful ones out there produced in large quantities by established brands with the infrastructure to support them. Many of which, may I add, offer reasonable value propositions and excellent performance.

I do, however, take issue with the often seen wholesale discounting of the practice by many companies of using sourced movements from companies such as ETA, Sellita, etc… Even educated consumers are quick to call these watches boring, or of low value simply because the engine inside isn’t made by the company on the dial. I would prefer a sourced movement unless an in-house-made movement has clear advantages over sourced ones and real benefits to the consumers outside of a nebulous notion of prestige and exclusivity which, in my opinion, should be lower on someone’s list of things to scrutinize in just a movement contained within the more complicated architecture of a wrist watch.