Over more than a decade here on aBlogtoWatch, we have extensively covered the defining craze of the 21st-century watch industry: in-house watch movements. These are calibers that are produced or said to be produced by the same company whose name is on the dial, presented with limitless fanfare and one-upmanship to convey how exclusive, in every sense of the word, they are. A decade into so many brands developing and making exclusive movements should have watch enthusiasts reveling in choice, performance, and watchmaking beauty. This has only partially come to be; the rest of the time, we’ve had to endure disappointing news revealing how our favorite parent-group-owned movement suppliers copy license other brands’ homework, or debut thoroughly underwhelming movements. But — gather around — there’s a cool way out, and I have a hunch we might be seeing more of it in the decade to come.

I wrote about the creation, history, and practices of ETA, the lifeline movement producer of the watch industry until very recently. I mention ComCo (Switzerland’s Competition Commission) and how the Swatch Group, the owner of ETA (the movement supplier to a great many non-Swatch Group brands), sought a way out from ComCo, forcing it to sell truckloads of movements to competing brands. You’ll want to read that whole story, but in a nutshell, for a number of historical reasons that I also present in that article, ETA was forced by law to keep on delivering movements to virtually anyone who knocked on its doors, including some of the brands that presented the fiercest competition to Swatch Group’s luxury and mid-tier brands. The whole thing has, in a way, culminated and indeed backfired, but we are not here to reiterate that entire story.

Fast forward to 2023, and most all of those luxury and mid-tier brands, and even some truly affordable ones, have set up their own internal supply of more or less exclusive movements. On the absolute mess this has created, check out my article The Inconsistencies & Current State Of “In-House” Watch Movements And What We Can Do About Them because there was and still is a lot that needs to be done about said inconsistencies, and, indeed, the expectations and double standard mentality the watch enthusiast community has when it comes to judging in-house movements. A lot is said and discussed in that article and its comments, so be sure to not miss it once you are up to speed on the history of ETA.

Having set up shop and developed their first in-house movements at absolutely tremendous expense, watch brands were quick to realize they should get their money’s worth and start advertising their in-house calibers as the be-all and end-all of horological refinement, performance, and exclusivity. As it happens in virtually any industry in the capitalist world, sometimes these lofty claims were all but backed up by real-world performance. What the past decade, dominated by this push to increase production and communication of “manufacture” movements left us, watch consumers and enthusiasts, is an incomprehensible variety of different watches equipped with more or less different movements.

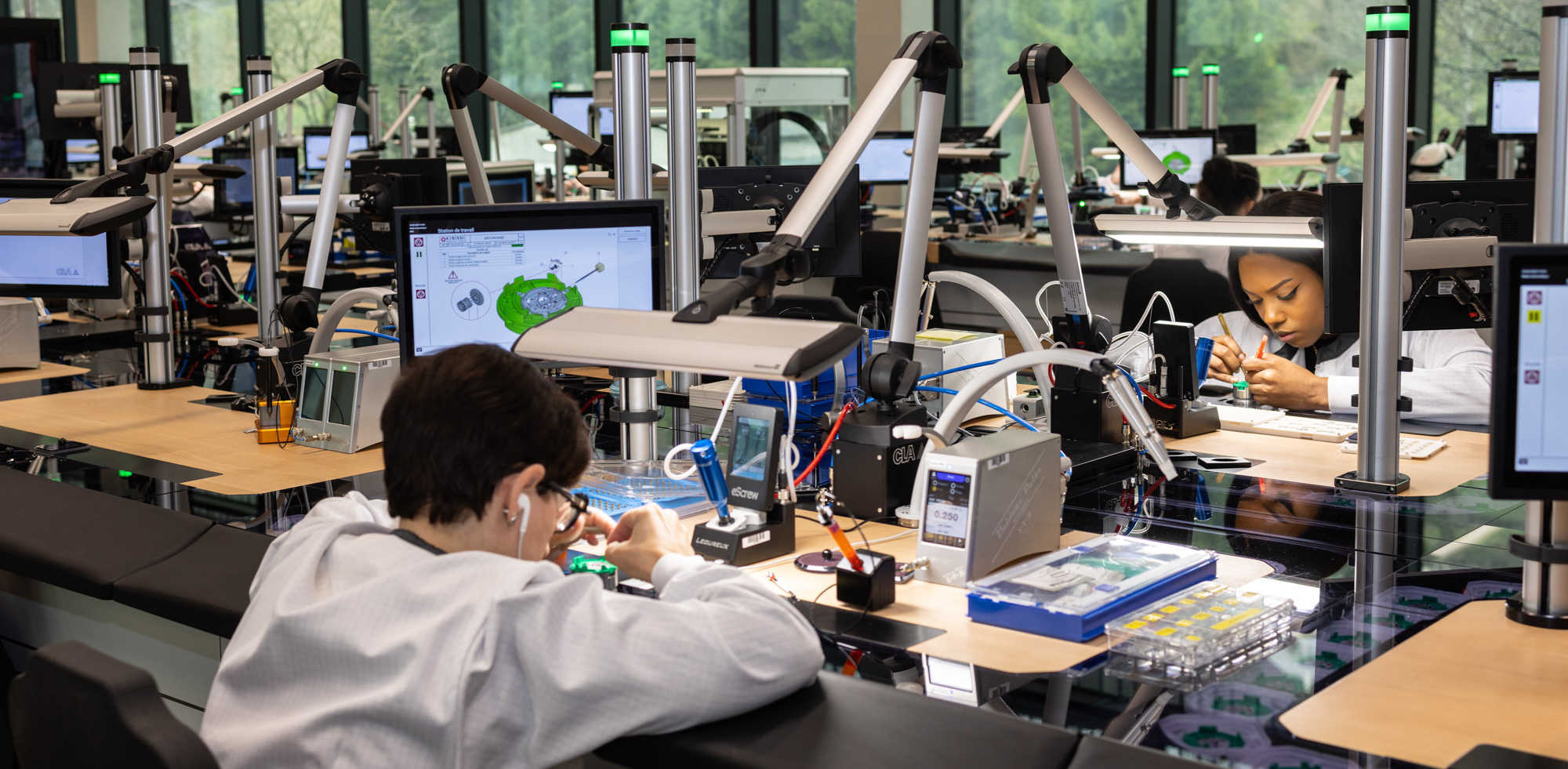

Again, it’s impossible to overstate the brands’ desire to make the most of this situation they were put into by Swatch Group and its ETA movement supplier. They had to expensively engineer their way out of being cut off from the supply of fine movements on which they had relied for so long, and even before they could do that, many had to invest in manufacturing facilities — we are talking about millions to tens of millions of Swiss francs, here. “We’ve invested about 40 million Swiss francs into our production facilities over the last five years,” Stephane Linder told Reuters back in 2013 when discussing the then brand-new new Chevenez facility. Many brands had to create ETA-substitute movements, often with identical dimensions (diameter and thickness and mounting points) so that they could be fitted without having to re-engineer the case and dial, too. This had many of these “in-house” movements be identical in terms of specifications and layout to supplied movements, and this was possible because the patents on just about all the popular ETA movements had expired long ago. More importantly, the vast majority of the resulting in-house movements offer no new features — they tend to be three-hand movements with a date, less often a chronograph, and less often, still, a calendar attained by slapping a module on the dial side. They seldom bring any meaningful improvements in terms of accuracy and utility through increased chronometrical performance or power reserve.

A unique dial layout on an otherwise familiar complication is often a good indicator of a unique movement.

This is not to say the past decade had not given us some fantastic in-house / manufacture calibers because it has, and these we praise here on aBlogtoWatch in our reviews. But they are outweighed by the number of mediocre movements with “in-house” pedigrees, movements that had to be developed for two key reasons: 1) Due to ETA finally being allowed by ComCo to stop selling to those it does not want to, and 2) Because brands that just spent a fortune on a shiny new manufacture and millions of francs on the development of a new movement wanted to make the most of the exclusive status and unique selling point of their new proprietary caliber. This is to say they had not been in the mood to share their manufacturing capacities and movements with anyone else. Many of the brands affected by these doors closing in on them might have already been making one or two in-house calibers while leaning on ETA for the rest. Now, however, they had to scramble to expand their production and put their own ETA-inspired movements into production — again, with the same specs but now at considerable expense, with the customer only experiencing a price hike and the bragging rights that go with an in-house labeled ETA clone movement.

Behind the impressive rotor lies a movement made by Richemont-owned ValFleurier, not Vacheron Constantin.

In a nutshell, then, it is safe to say that many of today’s “in-house” movements are underwhelming, either because of their mediocre performance and feature set, or their smoke and mirrors provenance (as discussed in the “Inconsistencies & Current State Of ‘In-House’ Watch Movements” article).

So, what’s the “cool way out?” Collaborations. More specifically, brands and manufactures with truly excellent modern movements delivering these calibers to competitors. This naturally depends on said competitors letting go of their expensively developed mediocre movements and reaching an arm out to those with better products, and the latter having what it takes to share them. We must not forget that we are talking about the luxury watch industry, where the status and prestige of a brand are every bit as important as its watches keeping time — if not with impressive accuracy, then at least with acceptable accuracy. Brands thrive on their ability to communicate how and why they are different and superior to all their peers and why the customer should want to signal their own success with them, as opposed to all others.

The Zenith-powered TAG Heuer Caliper Chronograph RS from 2008 is a great example of how a brand can tune a supplied movement and make its own.

Still, many brands will find in their archives quite literally tons of watches that they have produced with movements provided by another watchmaker. During most of the 20th century, it was not the exception but the norm for watch companies to buy movements from others — just how cases, dials, bracelets, and other parts were sourced from their respective specialist suppliers. The creation of almighty luxury groups with infinite funds has kickstarted the acquisition-frenzy of not just independent movement factories but also these other independent suppliers of habillage.

Audemars Piguet, Patek Philippe, and Vacheron Constantin have used Jaeger-LeCoultre movements for ages, just how the gorgeous Valjoux 72 has powered many drool-worthy and, today, highly collectible watches. Piaget, the master of ultra-thin movements in the last century has also supplied its calibers to others — in fact, it was first a movement component maker (from its establishment in 1874) and began selling watches under its own name only much later in 1943 (without stopping to supply movements). Some of the coolest brands today have used base movements from others without ever affecting their status. MB&F used Girard-Perregaux base calibers, Richard Mille has been relying on Parmigiani Fleurier’s Vaucher Manufacture (which we visited in 2013 here), and probably the coolest Chanel watches of all time is the H2129 that is powered by an Audemars Piguet 3125 caliber (based on the AP3120). Tudor has teamed up with Breitling and offers a modified Breitling B01 movement in its Black Bay Chrono for thousands of dollars less than any B01-equipped Breitling. Has this caused Breitling any trouble? Apparently not, as Breitling keeps racking up one record-breaking year after the other. In turn, Tudor supplies Breitling with its excellent MT5612 automatic movement with a date, although the movement is actually made not by Tudor but by Kenissi which Tudor owns in part.

We could mention a few other such noble and impressive sharing of watch movement production capacities and know-how, but don’t let this apparently long list misguide you: Such collaborations, by and large, remain the rare exception and not the norm. The point, in conclusion, is that many major players in the industry have scored big by reaching out to competitors and sourcing their movements, as opposed to expensively developing their own calibers that, potentially, would have been inferior in just about every regard.

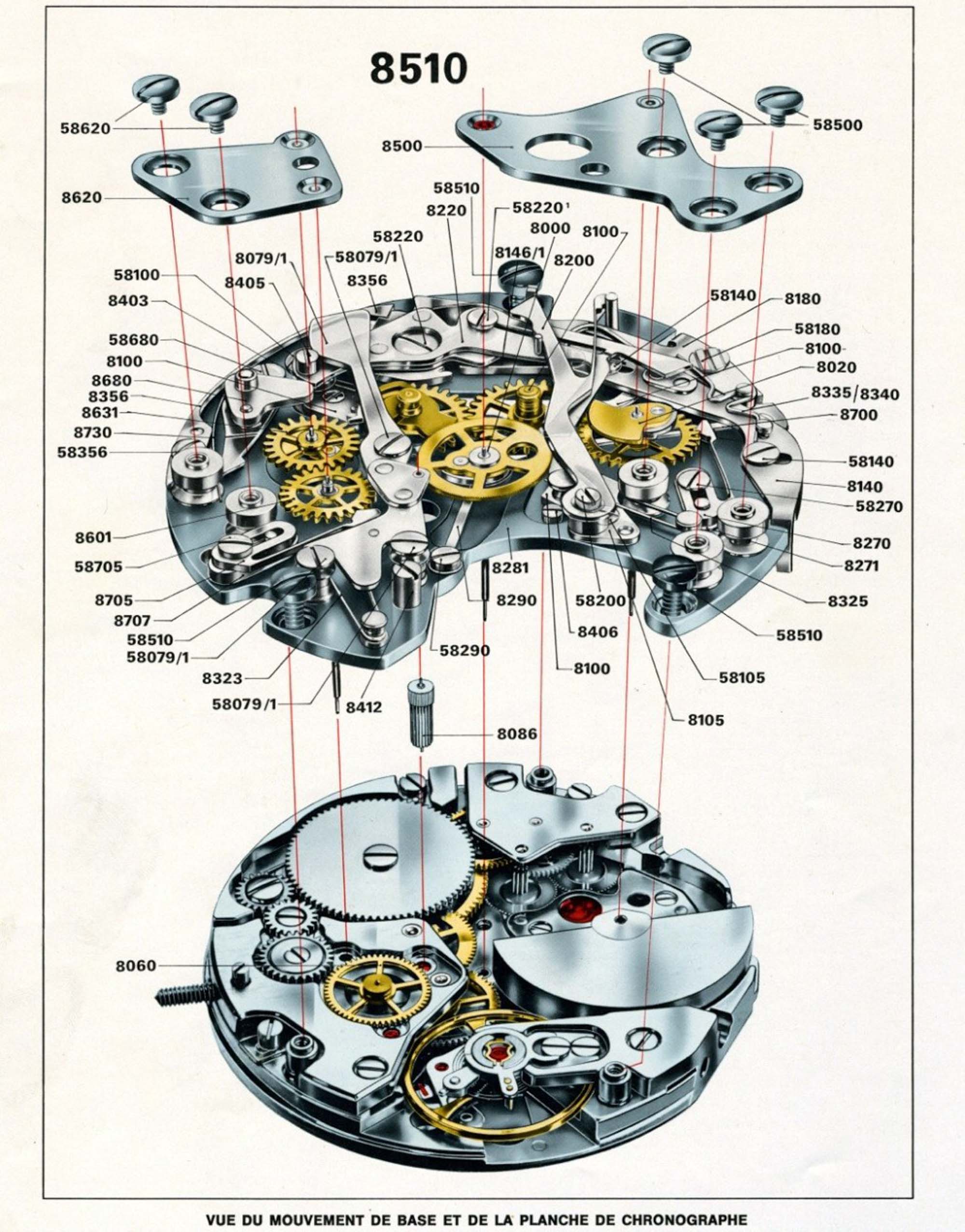

I am not suggesting that movement development should be stopped or that turning these collaborations into reality wouldn’t have its very own challenges. I do believe however that movement development and production should be left to those companies with the means to do it right so that the rest can focus on what they do best. Engineering supplied movements received from other brands into one’s very own watch collection is already difficult — there are countless measurements, specifications, technical requirements and more to be taken into consideration when tailoring cases and dials to fit the “hard points” of these calibers — but still a lot less daunting than developing a fine, efficient, durable movement from scratch.

Furthermore, honesty and openness about the true sources of these movements is naturally a key component to this success, and we have criticized those that weren’t as open as they should have been (you’ll find those notes in the hands-on or news coverage we published about many of the collaborations mentioned above). In fact, I would love to see brands loudly promote the fact that they managed to score a collaboration with a renowned movement maker — collabs work incredibly well in the fashion, consumer electronics, and automotive industries (to name a few), and we have seen collectors drop everything to own a rare collaboration piece from their favorite brand. Some even pay huge premiums for a co-signed dial, and it’s fair to say we are talking about something much more tangible and meaningful when it comes to shared movements, as opposed to dial prints.

The fine print to support this proposition goes on infinitely, as the origin of watch movements and the related communication issues is a bottomless can of worms, really. That said, at the core of this installment of the Grinding Gears column is a desire to see more brands reach out, not just within the confinements of their parent luxury groups, but beyond, so that a watch industry that celebrates truly great performance and artisanship takes the place of one that revolves around dubious prestige. Let us know in the comments below if you have room in your collection for a big-brand watch — powered by a movement by a competitor.