Written by Ashley Sandeman and edited by Ariel Adams

The first time I saw a Star Trek replicator, I knew I had to have one. And high on the list of objects I’d like to print at home is my own mechanical watch.

But despite all the promises of 3D printing technology, miniaturizing metallic parts at a watchmaking scale has remained elusive. Hopes, however, remain high as the technology in question is evolving rapidly. Cracking the shell of the 3D-printed metal mechanical watch movement could forever change the economics and power bases of today’s luxury wristwatch industry.

Back in 2014, I became excited by the work of watchmaker and software engineer Nicholas Manousos, who 3D-printed the Tourbillon 1000%. Printed in PLA (Polylactic acid) plastic at a ten-fold size increase of a normal tourbillon, this was part of a larger project to produce a fully functioning movement. It was later abandoned due to technical challenges.

In 2016, Christoph Laimer gave us further hope. He 3D-printed a tourbillon pocket watch at 98mm in diameter that ran for about 30 minutes using a consumer-grade printer.

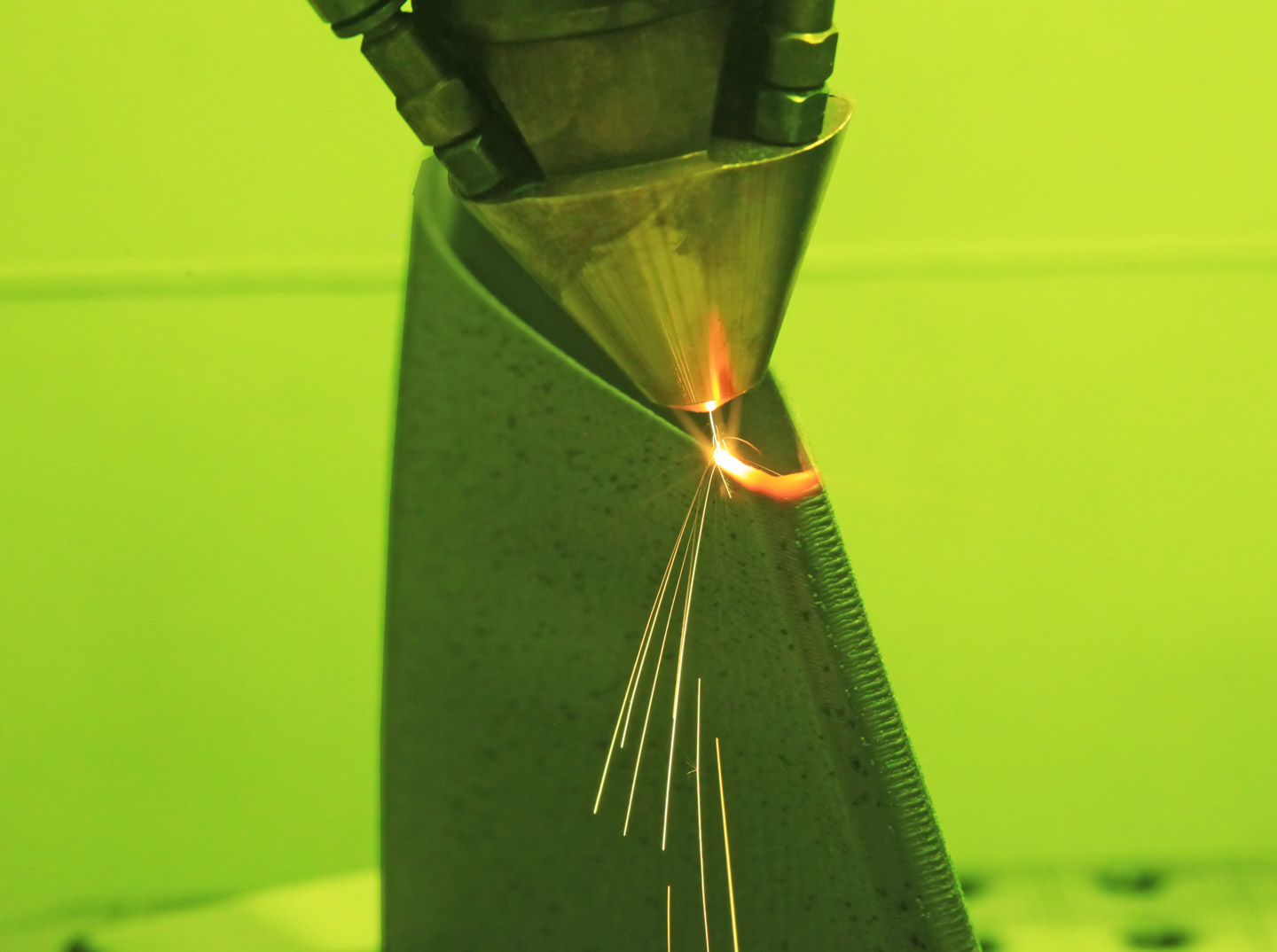

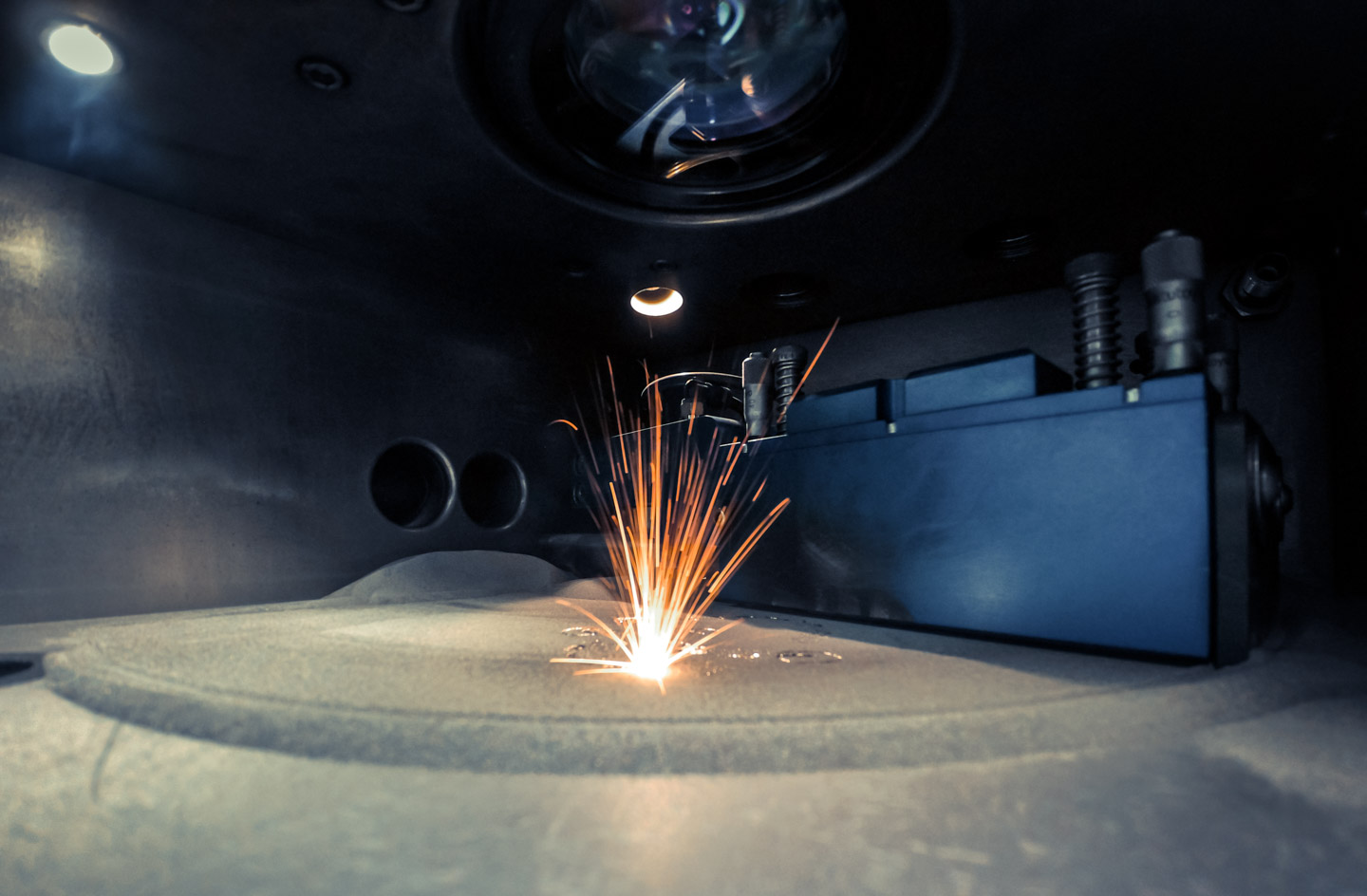

More recently, Panerai used the 3D printing technique DMLS (Direct Metal Laser Sintering) on the case of the Luminor Marina – 44mm (PAM01662). This makes Panerai one of the few companies to take 3D printing to production. Elsewhere, we’ve seen 3D Printing used for rapid prototyping in R&D departments at IWC, A. Lange & Söhne, Parmigiani, and the R&D Q-Lab at Roger Dubuis. Admittedly, these uses are not related to internal watch movements or mechanisms. Rather, they are mostly decorative or helpful in the context of testing new product designs.

Over the same recent timeframe, the most visible miniaturization of consumer technology means smartphones can now replace laptops. And your smartwatch can replace some functionality of your phone. So, with all these advancements, why isn’t anyone able to solve the challenge of 3D printing a fully metallic watch? The answer comes down (ironically) to accuracy and precision.

The layperson might think 3D printing a watch is straightforward. You take a CAD model of the watch, feed it into a machine, and out pops your product. No more Rolex shortages, right? But while we can print basic parts at home in rough plastic, it’s more complicated when it comes to precise metal parts. And with regard to 3D printing, the frontier has moved beyond plastic. Certain forms of metal can now be 3D-printed, as well — which is where real watchmaking comes in.

Timepiece aficionados often forget that beneath the dial, a movement’s components make up the majority of parts in a watch — which typically number in the hundreds of — if not several hundred — parts). Precision intolerance is one of the major reasons we haven’t seen printed movements yet. The current landscape of commercial and industrial 3D printing machines simply aren’t suited for the tiny sizes and near-perfect tolerances even the most basic of mechanical watch movements require. In many ways, the industrial machine that the traditional watch industry built to mass-produce precision parts is a key component in its longevity. Much of the know-how remains tightly guarded at companies in Switzerland. For example, there are only a handful of companies that can produce their own regulation system balance springs. The Swatch Group’s Nivarox is among the few companies that can mass-produce them — and they still don’t have very many competitors.

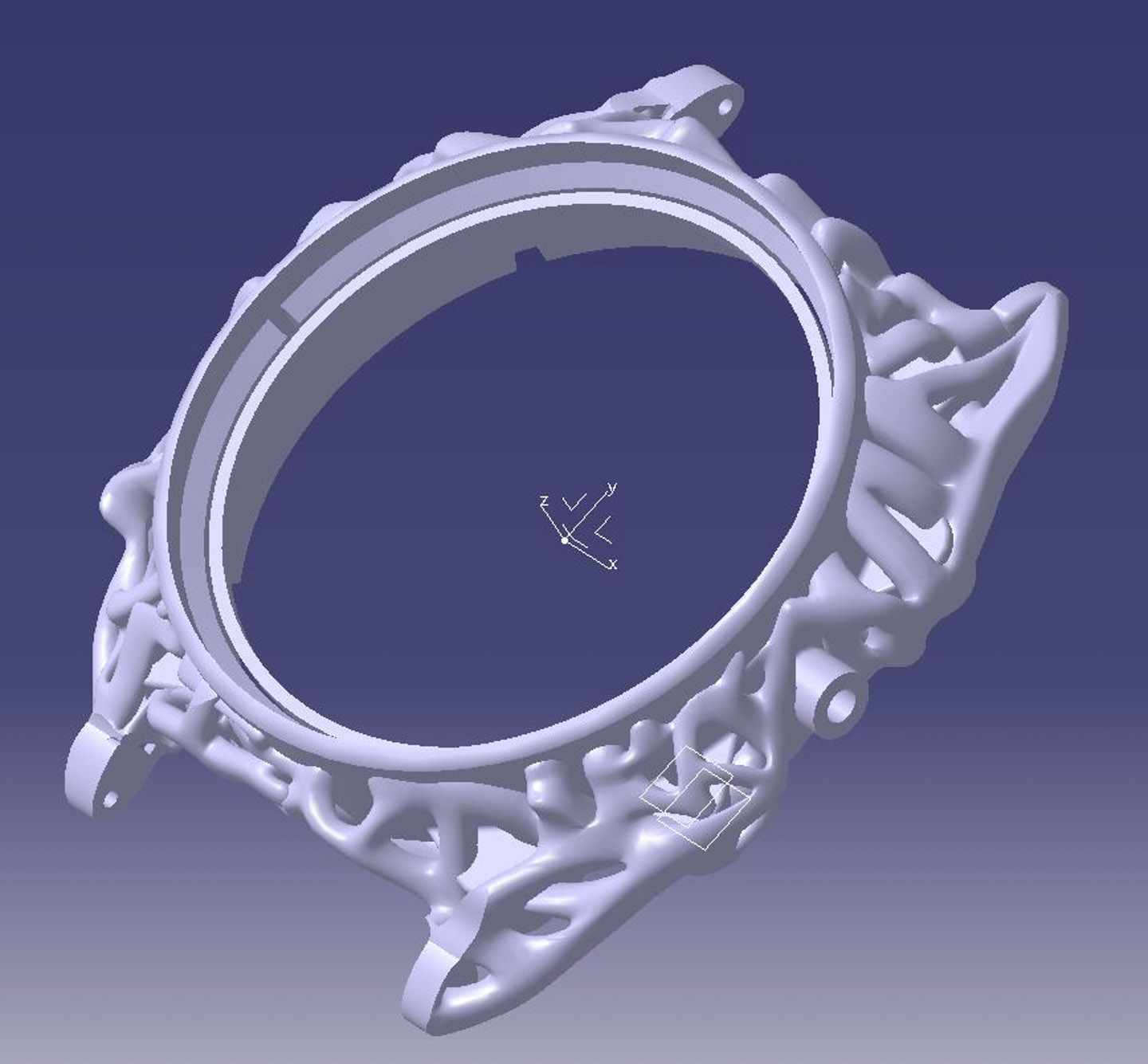

To help understand the 3D printing precision gap, I sat down with British watch designer, aerospace engineer, and expert in 3D printing, Gregg Cowell. Cowell has undertaken this challenge over the past three years and answered using his pictured prototype watch to illustrate. The watch was produced using production-level manufacturing equipment across four different locations in the UK.

His watch (pictured within this article) demonstrates what different 3D printing techniques can achieve (and not necessarily mainstream tastes). The case is produced under high-resolution laser titanium melting. Cowell has taken his prototype further, printing a single interlinked bracelet using a coarser powder mixture under a standard resolution titanium laser method. Meanwhile, the bracelet clasp is produced in steel using binder jetting, as printing titanium is prohibitively difficult at the scale of the clasp. Finally, the high-finish rhodium dial is produced using a mixture of old and new technology called lost wax casting.

The different techniques are important, maximizing the product definition of each part. For example, Lost wax casting was used on the dial of Gregg’s watch because it produces a better finish than laser sintering. Similarly, the DMLS process used to produce the Luminor Marina case isn’t suitable for the precision parts of movement manufacture because where laser melting is used, it produces tiny surface bubbles that must be removed after printing. The difficulty comes in manufacturing highly finished parts small enough and strong enough to withstand the forces generated by the movement. There are new and experimental miniaturizing processes, such as MICA Freeform, but this focuses on sizes too small to replicate traditional escapements. Cowell has produced a metallic escapement fork but has been unable to achieve a tolerance for it to operate in a working movement.

The different techniques are important, maximizing the product definition of each part. For example, Lost wax casting was used on the dial of Gregg’s watch because it produces a better finish than laser sintering. Similarly, the DMLS process used to produce the Luminor Marina case isn’t suitable for the precision parts of movement manufacture because where laser melting is used, it produces tiny surface bubbles that must be removed after printing. The difficulty comes in manufacturing highly finished parts small enough and strong enough to withstand the forces generated by the movement. There are new and experimental miniaturizing processes, such as MICA Freeform, but this focuses on sizes too small to replicate traditional escapements. Cowell has produced a metallic escapement fork but has been unable to achieve a tolerance for it to operate in a working movement.

An easy way to improve 3D printing precision is to simply make a finer writing instrument. In 2014 the hefty size of the Manousos Tourbillon 1000% was dictated in part by the nozzle width-limitations of the printer and the tolerances required to make it function without ripping off gear teeth. Manousos wasn’t able to achieve the needed tolerance precision with 3D-printed plastic until working at 1000% of the original metal movement’s size. Cowell likewise believes traditional escapement designs are ill-suited to manufacture given the current limitations and capabilities of current printing technology.

As watch lovers, we can only speculate that applicable 3D printing experts over at the larger watch brands have all come to similar conclusions about how 3D printing currently can’t do much for them. Today, 3D printing technology isn’t well-suited to the lilliputian part size-needs of traditionally manufactured watches. That said, the tolerance of 3D-printed metal (in combination with some finishing processes) might be a welcome addition to the construction of watch cases and other structural elements.

I asked Alessandro Ficarelli — Product Development Director at Panerai — why the brand chose a 3D-printed component for a case construction part for the PAM01662, and also what developments we can expect to see next from the Panerai Laboratorio di Idee. Here is what he said [edited]:

“3D printing technologies are often used for prototyping since the quality level normally reached by the printed material is not sufficient for production parts. “Panerai, after a long development phase … started with the improvement of the powders used as raw material and ended with the configuration of the entire 3D printing process. [Panerai] managed to achieve a quality of the printed material without equal. This material has no porosity; its behavior is perfect through all the printed part and makes it possible to produce technically and aesthetically perfect components, meeting the very high standards of Panerai. Looking at the future, we will further explore the universe of more durable, eco-friendly materials to ride the new sustainable challenges of tomorrow.”

This final statement refers to Panerai’s 2020 developments of the eco-sustainable basalt-fiber composite material Fibratech™ and the new EcoPangaea™ composite. It points toward another change we’ve seen since 2014: the rise of company eco-credentials and the environmental awareness of consumers that are driving innovation and sales. But that is another story altogether that aBlogtoWatch has also been covering.

In 2018, Roger Dubuis CEO Jean-Marc Pontroué was quoted in the South China Morning Post as saying there was a “high likelihood” we would see 3D printed movement parts in its watches by 2019. That date has passed, and Pontroué is now CEO of Panerai. I asked current Roger Dubuis CEO Nicola Andreatta if he could expand on the comments of his predecessor, but for now, Roger Dubuis is making no comment.

Unless that comment comes in the form of a product, it looks unlikely we’re on the verge of a 3D printing revolution in the mechanical watchmaking world. Like many industries, material developments in watchmaking are increasingly used to highlight environmental awareness. 3D printing is not as cool these days as saving the planet. But it is probably technology we need if we are ever going to get off this planet.

Relatively modest consumer demand for luxury 3D printed products makes it unlikely that many brands will invest in vanity 3D-printed watch case materials today. Consumers will spend a premium on products that apparently have some connection with earth-friendly sustainability — even if there is no direct evidence those products actually result in net gains for ecological impact reduction.

The current nerdy unsexy view on 3D printed components, from a pop culture perspective, makes it hard to imagine that established luxury watchmakers will be striving to press the boundaries of 3D printing technology, especially when the security of machined movements is under no threat from the market or driven forward by consumer pressure.

Watchmakers all seem to agree that if one could 3D-print metal watch parts it would be a game-changer — not merely in being able to mass-produce parts in a new way but also to solve some old problems while answering new ones. The vintage and restoration market will fundamentally change when brand new parts (that have the potential to again ask the question of what is “vintage”) for old watches can be produced out of relative thin air, and then simply polished to perfection. Creatives would also love the new level of design freedom afforded by an ever-expanded set of structural part opportunities. A 3D-printed part could easily befuddle even the most complicated of computer-controlled cutting (CNC) machines. What the CNC machine has on 3D printing today is, again, precision. Given the incredible promise to the watch industry afforded with the eventual availability of precision 3D-printed parts, the technology’s advent is worth watching out for.

Ashley Sandeman has loved watches since getting a Casio TS-100 at age six. Now a little older, he helps businesses deliver strategy and writes about watches, lifestyle, and fiction. He sometimes still wears the TS-100, and anything else he can. Connect with Ashley on LinkedIn.