I stumbled across what is called the Arcanum Digitecha, a digital library with 27,156,195 scanned pages of scientific and cultural content published in Hungarian from the early 1800s to date. Texts of encyclopedias, journals, and books are available to search just as though you were using Google. It’s a paid service, but I was happy to shell out the $50 or so for an annual subscription. Immediately, I enthusiastically dived into it, searching for the names of famous watch brands, watchmakers, and other news with what I’d hoped would be search terms specific enough to find watch industry-related articles.

Cool ads in the long-gone Hungarian Watchmaker’s Paper for Cuypers watch lubricant, tower clocks and the illustrious National Watch Factory can be found.

Be sure to check the date of publishing to determine the time frame of the news. Furthermore, please take these as what they are: news snippets and extracts of texts from times when there was a much more limited toolbox for fact-checking statements and stories. Do not take everything below as 100% accurate — but the fact that some papers thought these stories to be worth researching and publishing means there is at least some merit to the below. Lastly, I will try my best to bring the sometimes charmingly clumsy and inexpert tone of these Hungarian horological articles into English. Becoming a watch expert back in the day, especially just for the sake of a news article or two, was not a feasible idea. Without further ado, below you’ll find a selection of the most incredible and amusing news articles concerning the high times (and the low) of the watch industry… Oh, and there’s a Quartz Crisis Edition in the making, too!

Radiation Sickness From A Wristwatch — Kisalföld, August 30. 1961 / Issue 204.

“Willard Mound, American naval officer, in the name of himself, his wife and his five children, has sued Rolex, the American watchmaker for a compensation of 11,100,000 dollars. The naval officer purchased a Rolex-branded watch in Hong Kong in 1958, whose dial was made luminous with the use of radioactive isotope Strontium-90. The officer and his family have suffered serious issues: failing eyesight, trouble sleeping, fatigue, and skin lesions. Already last year, the American Rolex manufacture (sic!) had been forced to collect all pieces still in circulation and suspend production indefinitely.”

A super early reportage from 1958 on a “Rolex [Submariner] watch for frogmen” and its ability to keep track of dive times with a rotating bezel. Népszabadság, 1958

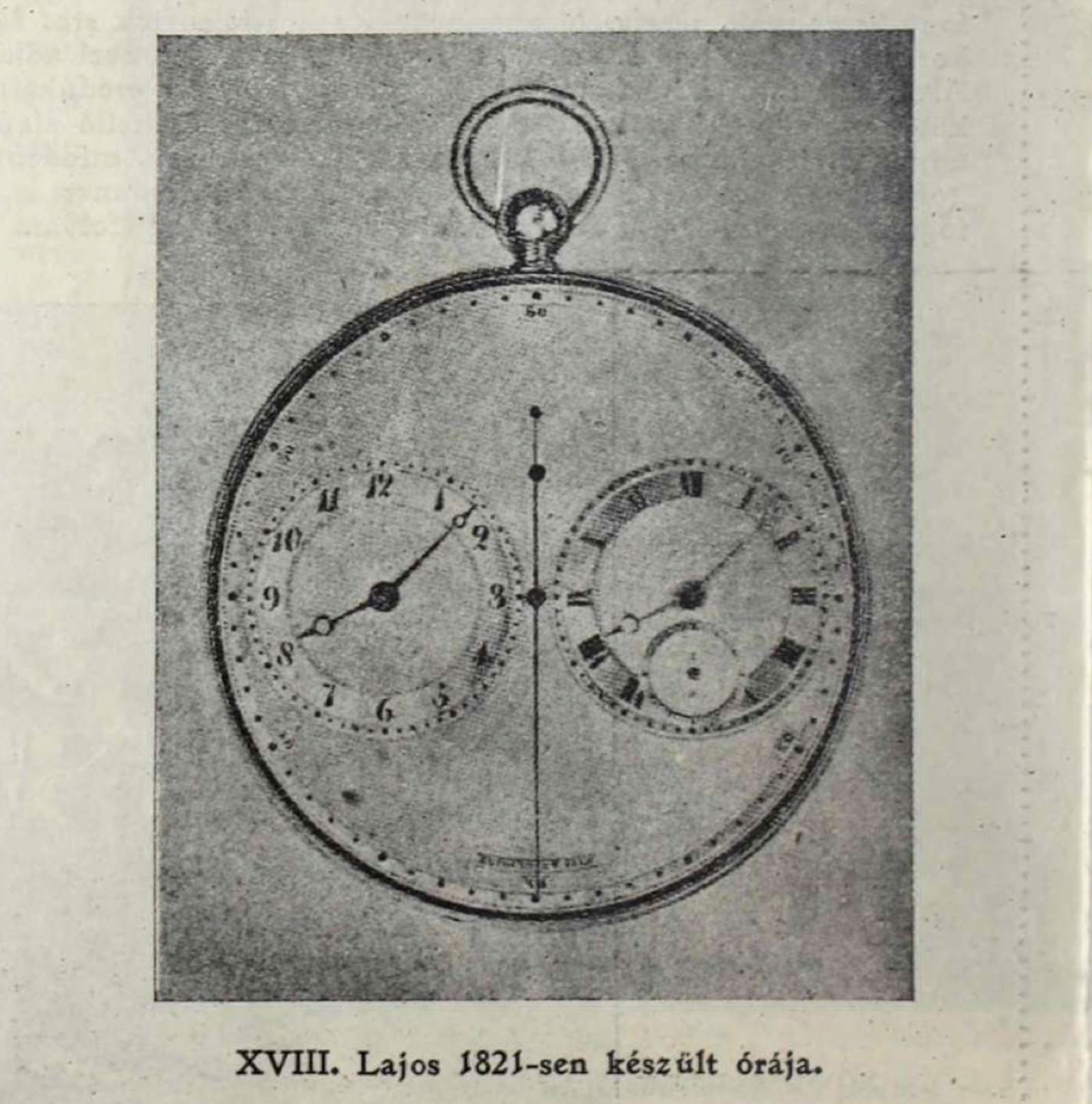

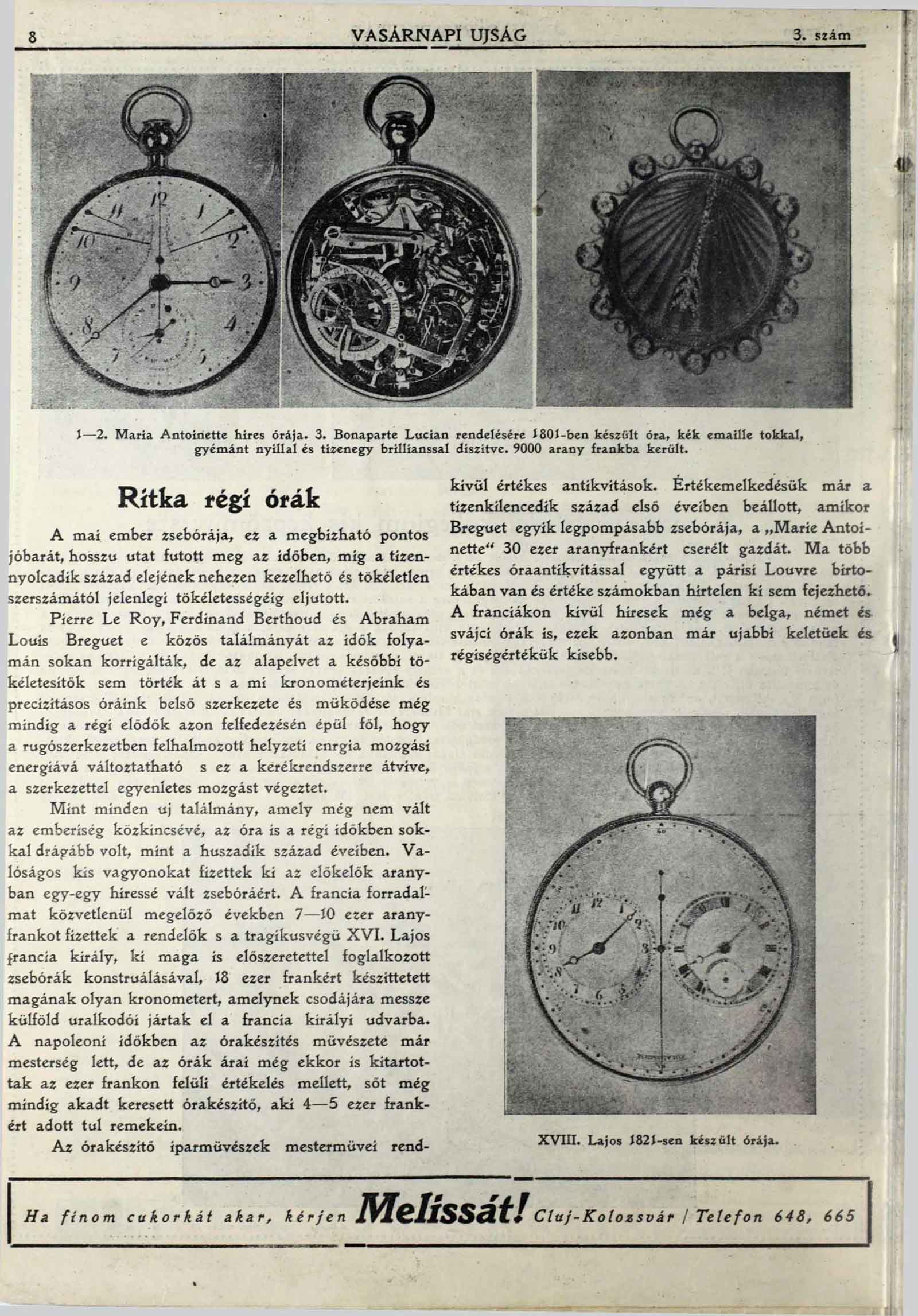

When The Breguet Marie-Antoinette Sold For 30,000 Swiss Francs — Vasárnapi Ujság, 1924. January 20 / Issue 3.

“The pocket watch, this reliable and punctual friend of today’s man, has run a long way in time before it turned from the unwieldy és imperfect tool of the early 18th century into today’s state of perfection. The shared invention of Pierre Le Roy, Ferdinand Berthoud and Abraham Louis Breguet has been corrected many times, but the foundations have remained untouched and so our chronometers and precision watches function on the same basic principles (…).”

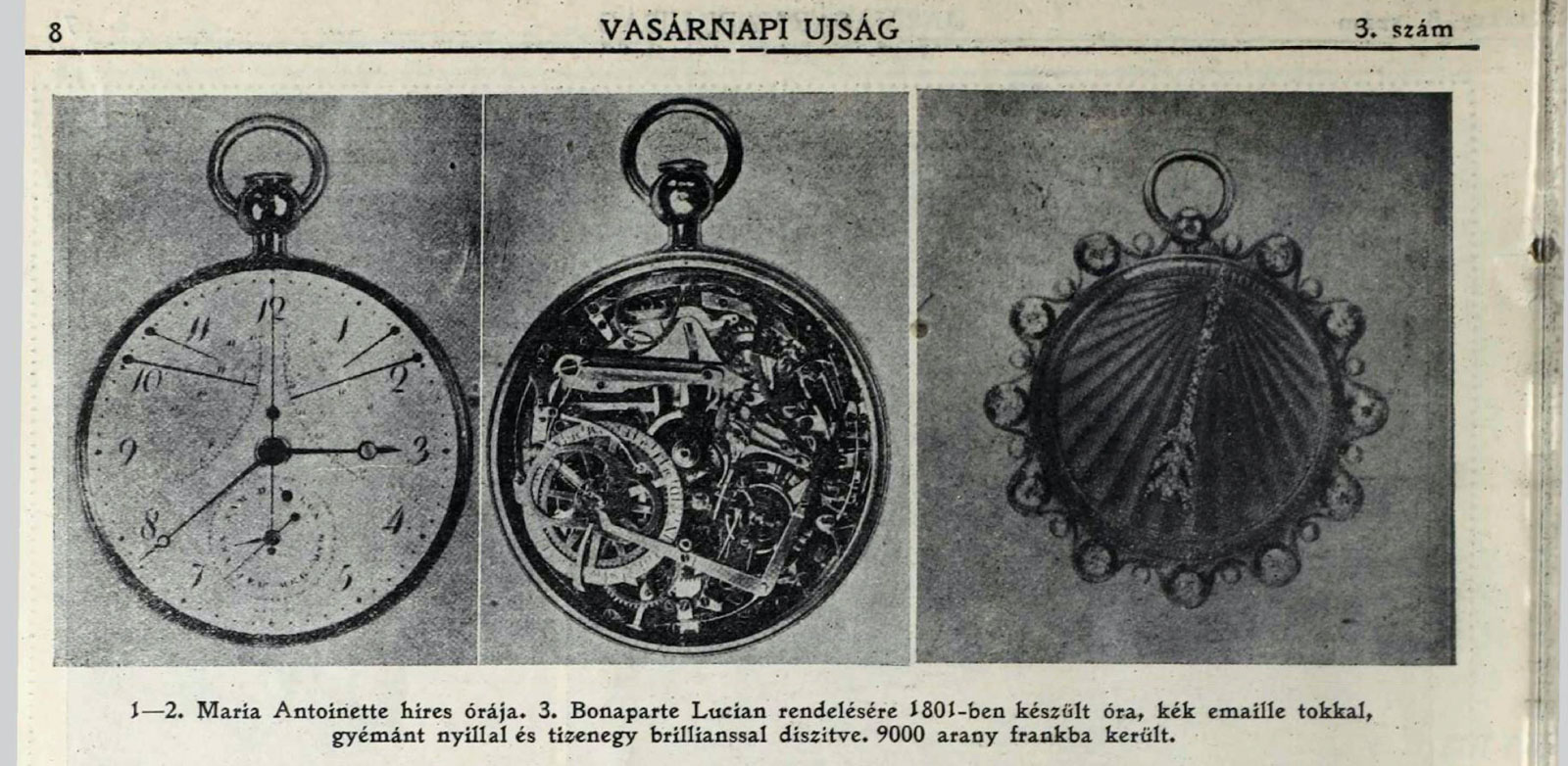

1-2. Maria Antoinette’s (sic!) famous watch. 3. A watch ordered by Bonaparte Lucian, finished in 1801 with a blue emaille case, diamond-set arrow and 11 brilliants. It cost 9,000 golden francs.

I have had the incredible opportunity to see that very watch (No. 3 on image, made for Josephine Bonaparte) at the Breguet boutique in Paris.

“Like every new invention that is yet to become mankind’s public domain, watches, too, used to be much more expensive in the olden times than in the years of the 20th century. Many have paid smaller fortunes in gold for a more renowned pocket watch. In the years preceding the French revolution, 7-10 thousand francs were paid and the tragically passed Louis XVI, for 18 thousand francs, had such a chronometer made for himself that foreign royals visited the French Royal court just to see it.”

“In Napoleonic times, the art of watchmaking has turned into a craft, but the watches remained priced over 1,000 francs, often reaching 4,000-5,000 with some watchmakers. These valuable antiquities have seen their appreciation reach its peak in the first years of the 19th century, when one of Breguet’s finest watches, the »Marie Antoinette« changed hands for 30,000 francs. Today, along with many valuable horological antiquities, it is owned by the Louvre of Paris and its value is mathematically inexpressible. Beyond French watches also renowned are the Belgian, German, and Swiss watches, though these are newer and their values are lower.”

Editor’s note: Frankly, I almost fell off my chair when I saw this snippet, “Maria Antoinette’s Changed Hands For 30,000 Francs…” among the hundreds of search finds when I searched for Breguet. Objectively the greatest, finest, most expensive and most incredible piece in the history of watchmaking, the illusive Marie-Antoinette watch by Breguet changed hands like a car, an estate, or a piece of jewelry.

Patek’s & Vacheron’s In-House Watch Movement Manufacturing vs. Ébauchers… In 1913! — Magyar Órások Szaklapja és Magyar Ékszeripar, 1913. August 01. / Issue 15.

“My peers will likely find the way Genevan watch manufactures work fascinating. At the major companies, such as Patek, Vacheron, etc., methods may differ slightly, but are very much alike, overall. The way they stand out is that the big companies produce most parts of a watch themselves and employ workers specialized in every respective component. The smaller manufacturers, on the other hand, who only make a few thousand watches a year, do not make the majority of a watch’s components, but rather outsource their production to independent workshops, i.e., they produce out-of-house.”

“The big companies (Patek and Vacheron) have dedicated, large workshops with automated machines to craft finished components from raw materials, such as dials (platinum), bridges, remontoir components, wheels, mainspring barrels, etc. The going train is also produced in-house and they employ a regleur [–the person responsible for adjusting timekeeping on an assembled movement; the editor] as well.”

“The smaller companies, by contrast, have to do completely without a mechanical workshop and use half-completed, so-called »ébauche« movements to create their calibers. There are multiple »ébaucher« or raw-movement-makers. Among the better known are Lecoultre & Co. in Sentier, and Ranaz in Saint Croix. (…) The deal between the raw-movement-maker and the small watch brand is as follows: The tools required for manufacturing, such as mills, drills, lathes and other tools the watchmaker has to provide, i.e., he has to pay for these, but gets to own them after all.”

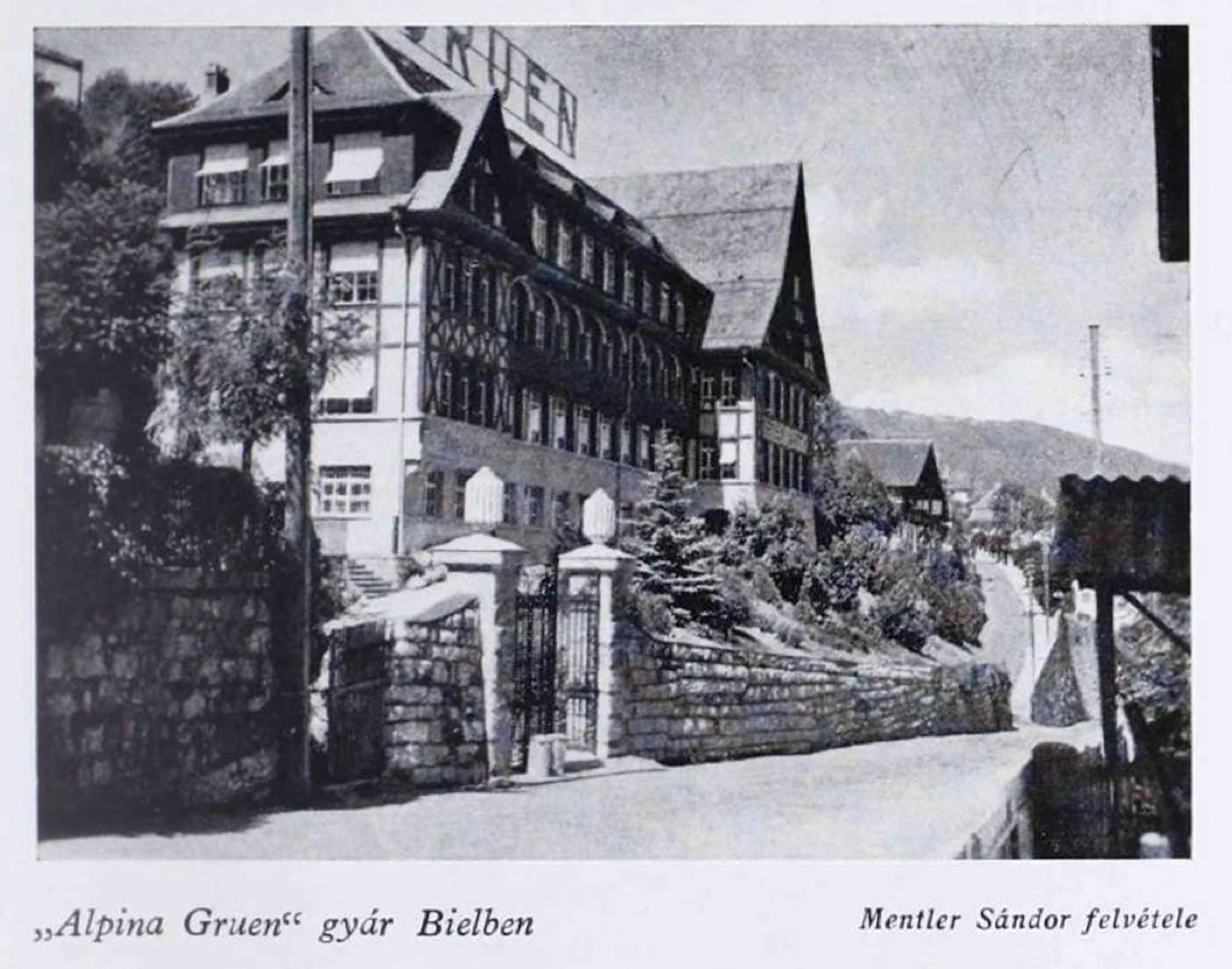

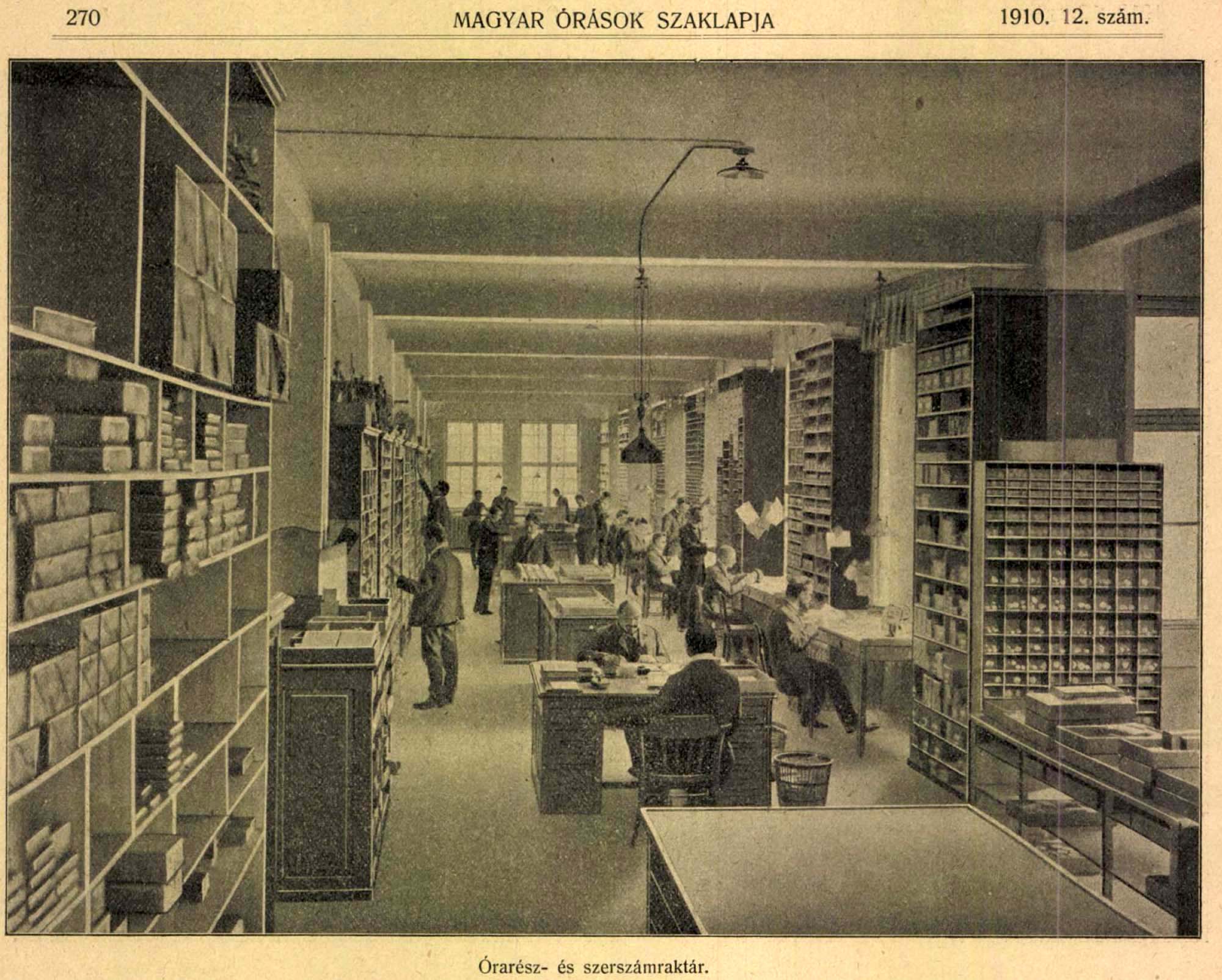

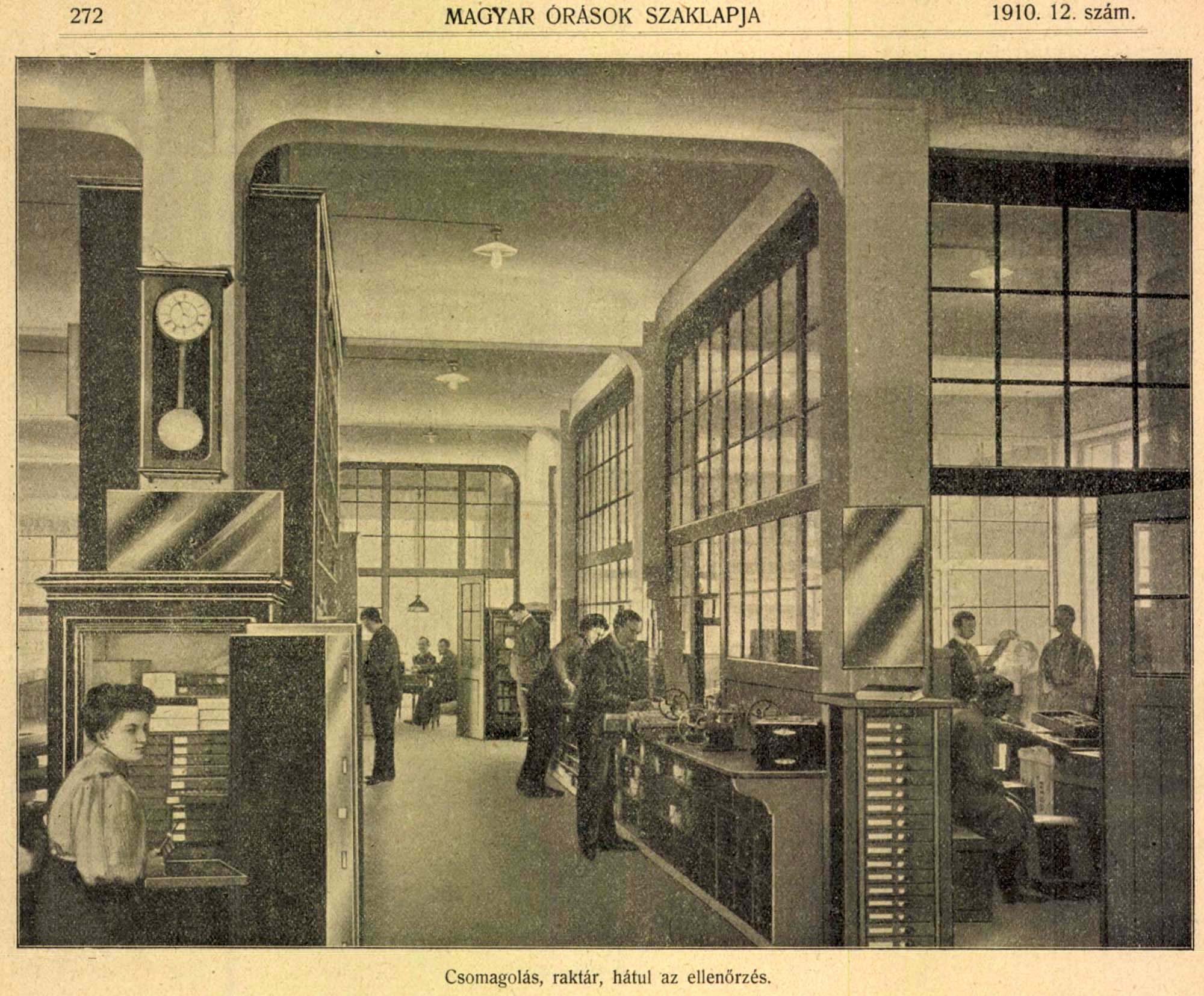

Unfortunately, we couldn’t find indoors images from watch manufactures of the era. These are pictures from the mighty impressive Ludwig & Fries Watch Components distributor in Frankfurt.

“He will always order a gros, a dozen from a movement of a given size. The raw movements cost 12-20 franc a piece, naturally made from first grade materials. All the movements are without a going train, anchor and balance. Going train production is a special craft to its own and so the brand will have one made in accordance with the quality required, i.e. a I., II., or III. grade going train. (…) First grade going trains will have a refined, precise set of wheels with the most delicate detailing. Refined ruby stones and polished pinions are used to ensure a soft winding feel. The edges of the bridges are beveled in a uniform way and gold plating is used generously.”

A massive safe, set under a pendulum wall clock, encapsulates a set of tidy drawers full with precious metal watch components.

“The »ébaucher« will deliver watches per pack, and each pack contains six watches and six raw movements. Every part of every movement is numbered. The pack is handed over to the visiteur, who will make sure all the grabbing points are correct, and if not, he will repair them. He takes delivery of the going train from the going-train-maker and checks for the trains not to be too deep and to be functioning correctly. If something is faulty, he will return it. The visiteur is responsible for every work performed, and so visiteurs are workers with excellent qualities who are paid generously.”

Editor’s note: I chose to feature this article because it shows how the Swiss watch industry struggle was just as real 107 years ago, as it is today. The biggest, wealthiest companies had economy of scale on their side, while the smaller ones had to make do with the — mind you, highly capable and versatile — supplier base of the time. The XXI century is a lot more challenging in that it saw the wealthy outright purchase some of the best suppliers and cut off all or most all others who couldn’t afford to do the same. To ponder the importance (or lack thereof) of in-house calibers, read our Point/Counterpoint article on the matter here.

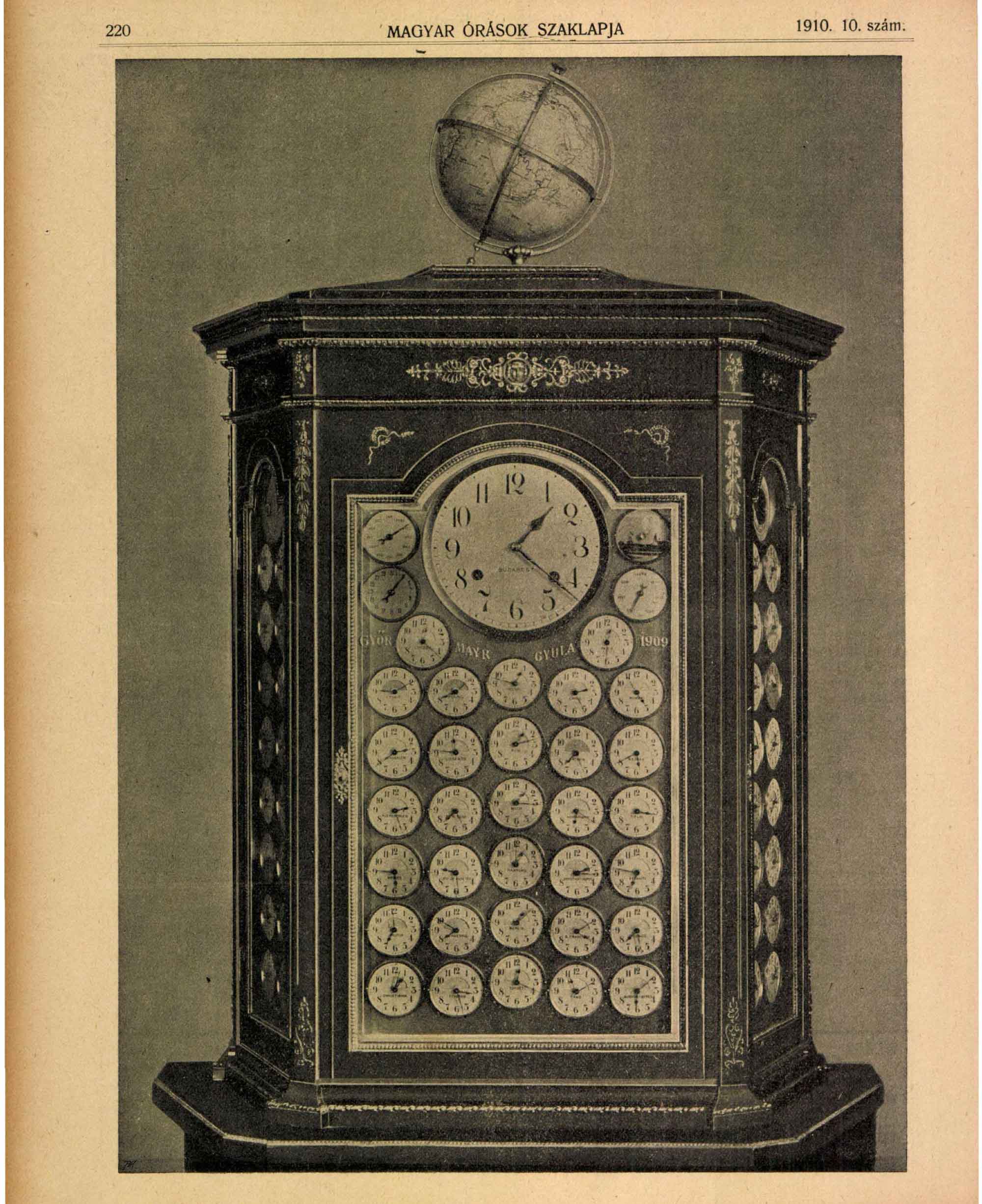

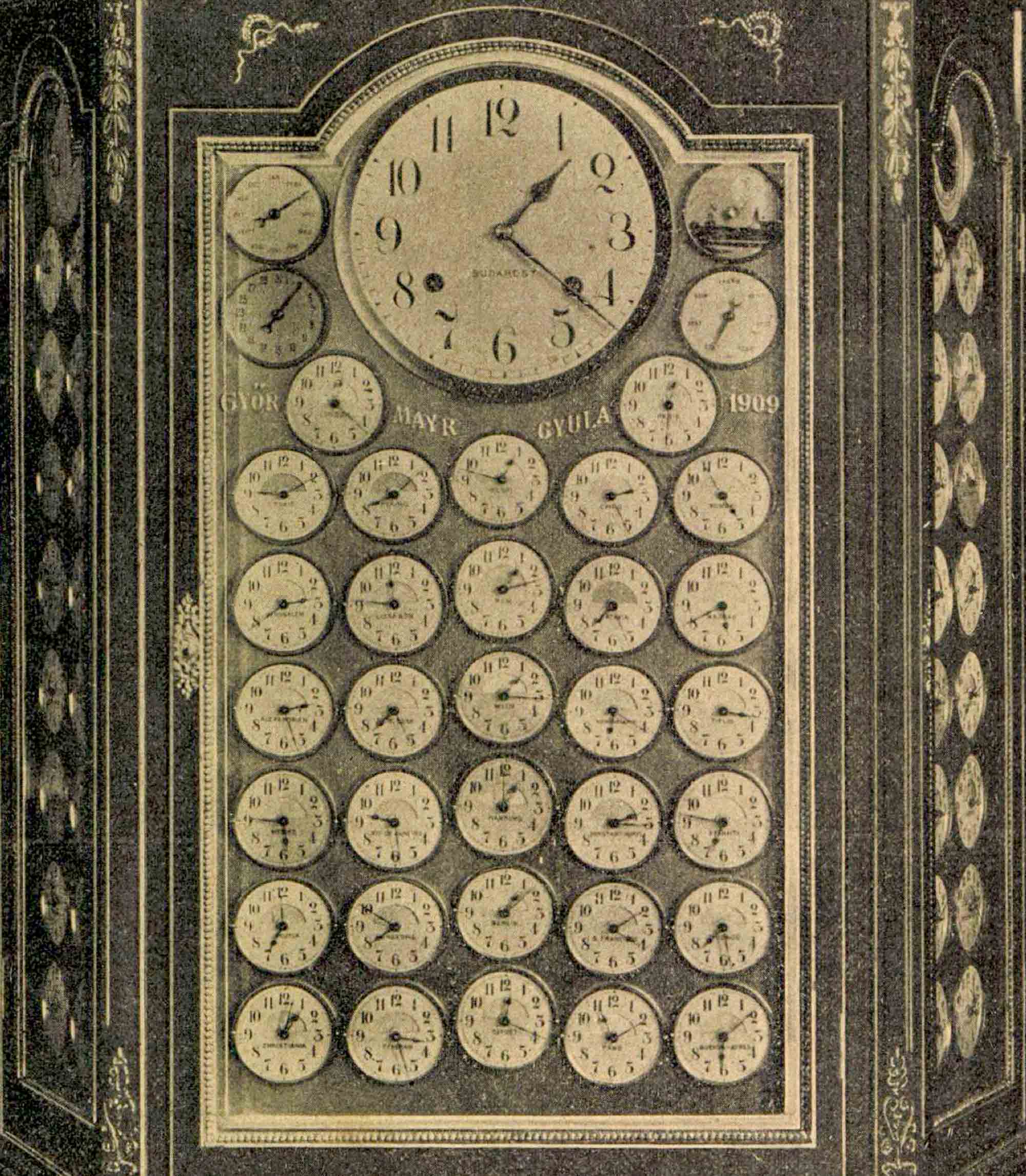

An Incredible 64-City Worldtimer Clock Made In Győr, Hungary In 1909 By Gyula Mayr — Magyar Órások Szaklapja, 1910. May 15. / Issue 10.

“This beautifully presented work took three years for Gyula Mayr [—Mayr Gyula in Hungarian; the editor] to make in Győr, with tireless diligence. A unique worldtimer clock that was literally an effort of patience that testifies to the dexterity of its maker. Worldtimers have been made before, but we don’t know of one of comparable magnitude. (…)”

A second version Mayr created with jumping hours by the order of the bishop of Vác. Source: Élet és Tudomány, 1984.

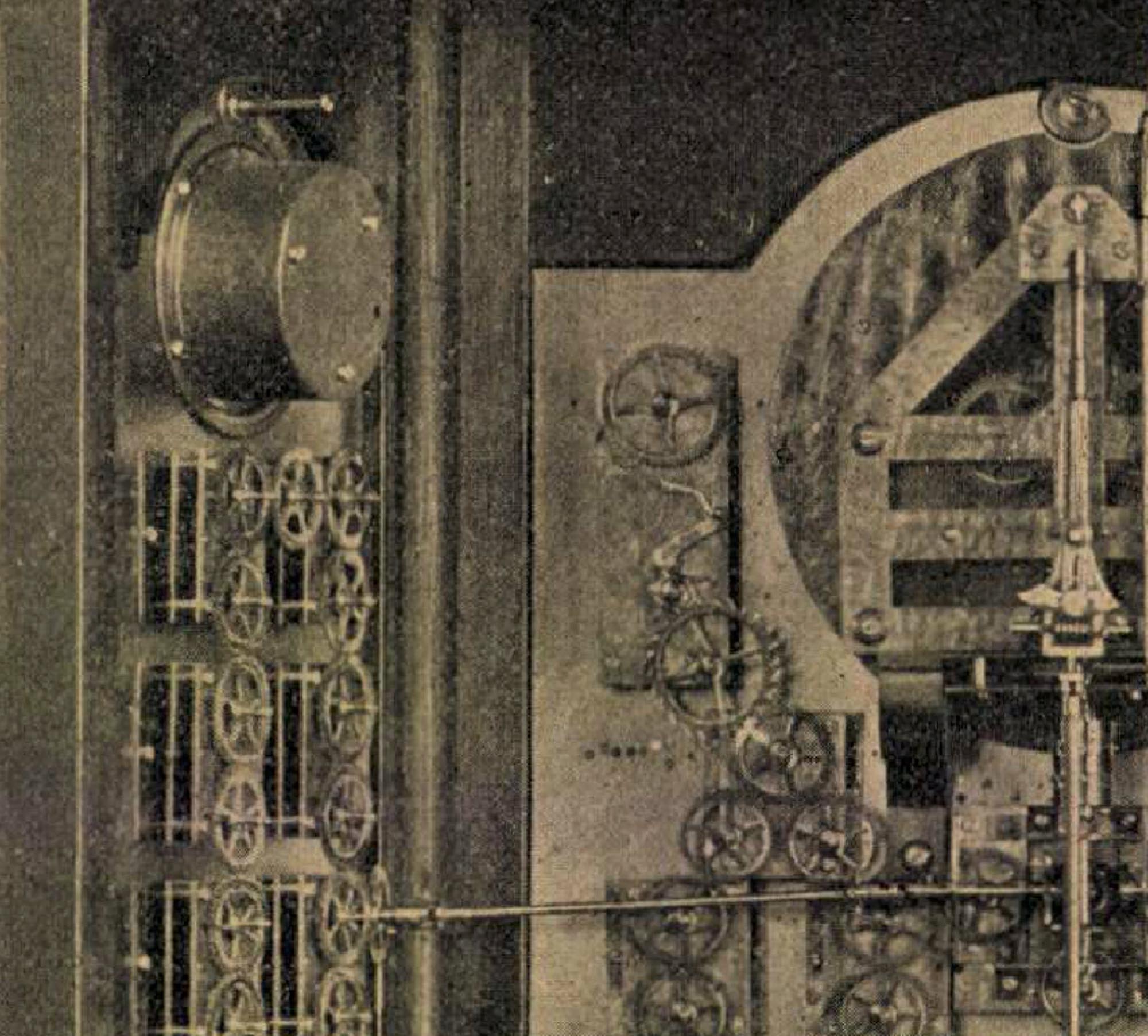

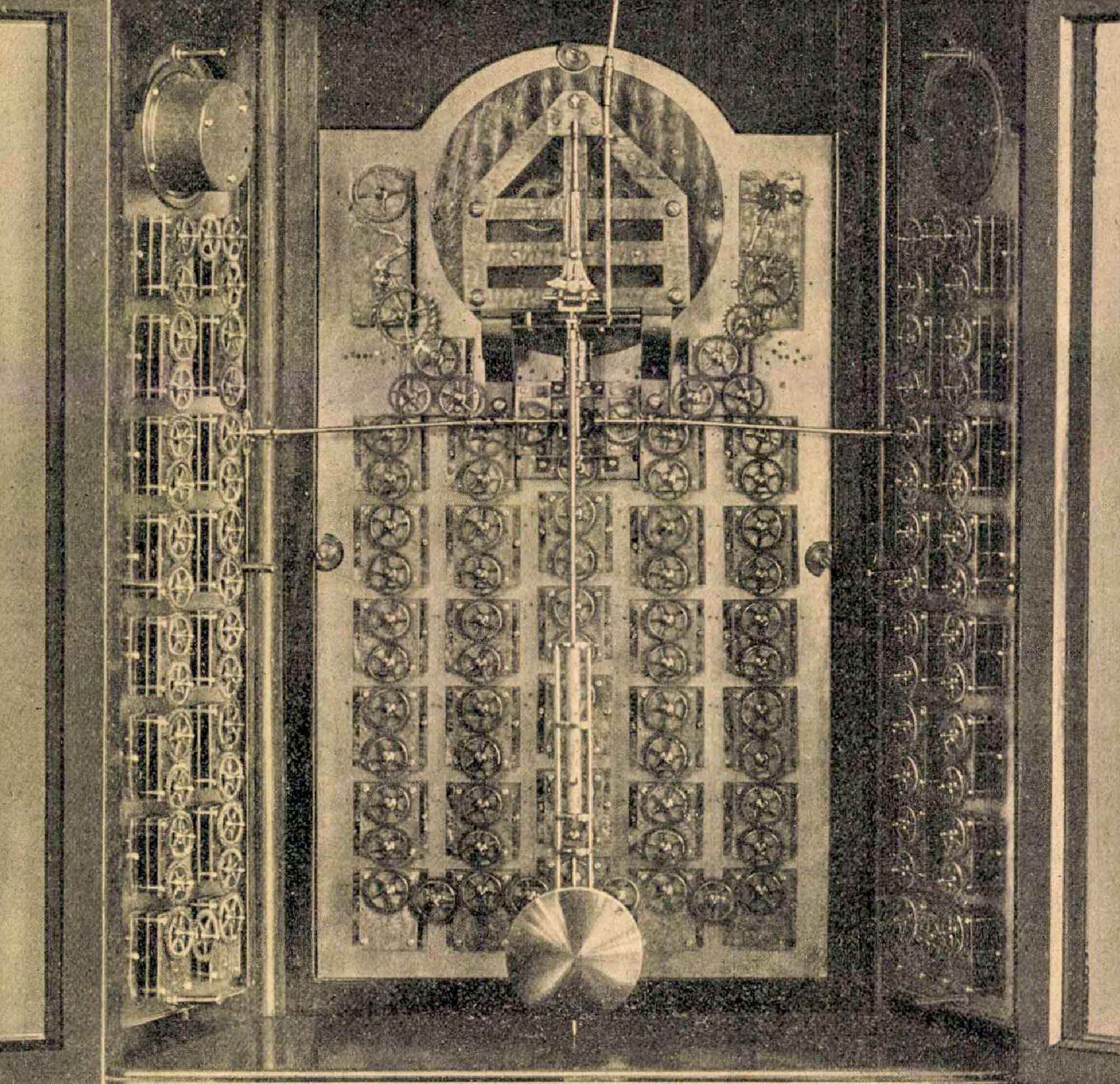

“Our pictures display this Worldtimer Clock from the front and the back, with its doors open so that the works can be seen. On the front, the large dial shows Budapest time; 32 others are below, and 16-16 are on its respective flanks. So that the night and day can be differentiated, every dial has a small semi-circle with blue for night, and white for day. This change occurs precisely at 6PM and 6AM. This is Mayr’s invention and nobody has done it like this before.” [—a bold statement, but made in the regularly published, watchmaker’s specialized magazine of the time; the editor].

“Four dials on the front indicate the number of the day, the name of the day, the months and the phases of the moon. The globe on top makes a full rotation once every 24 hours. The entire work is driven by a singular movement with two springs, requiring rewind every eight days. From the minute wheel an axle drives the 32 displays below, as well as the calendar. The side dials are driven by connecting rods, while yet another one going upwards drives the globe. As the picture tells, all the movements are split into three groups and are all connected, ensuring that no deviation in accuracy can occur between the different indications. On the sides one finds a weather forecast and a humidity display.”

“The clockwork has been carefully crafted with Graham-style stone plates [—my apologies, I’m not quite sure how to better translate this obscure terminology; the editor] and with a compensated pendulum with a special step-corrector. The individual times can be set independently, and they can all be removed and cleaned individually without the clock stopping to work. The cabinet was crafted from mahogany wood from the era of Louis XVI by Jenő Molnár [Molnár Jenő], teacher of the carpentry and metalwork school of Győr. As we look at this masterpiece, we wonder if such a gargantuan undertaking will pay off to its genius maker.”

Editor’s note: In retrospect, we know that pay off it did. The first 64-timezone clock was purchased by the minister of commerce to be placed in the Museum of Applied Arts, and a second, yet more complex clock with jumping hours and further indications, was commissioned by the bishop of Vác. Mayr’s and Molnár’s clock has won the Gold Medal at the Turin World Fair in Italy in 1911. Although during my research, I found that both Mayr Gyula worldtimer clocks have been exhibited recently, it was not until I found these articles over hours and hours of digging in the archives that I first learned about it. If your thirst for incredible clocks remains unquenched, check out Konstantin Chaykin’s Computus Easter clock here.

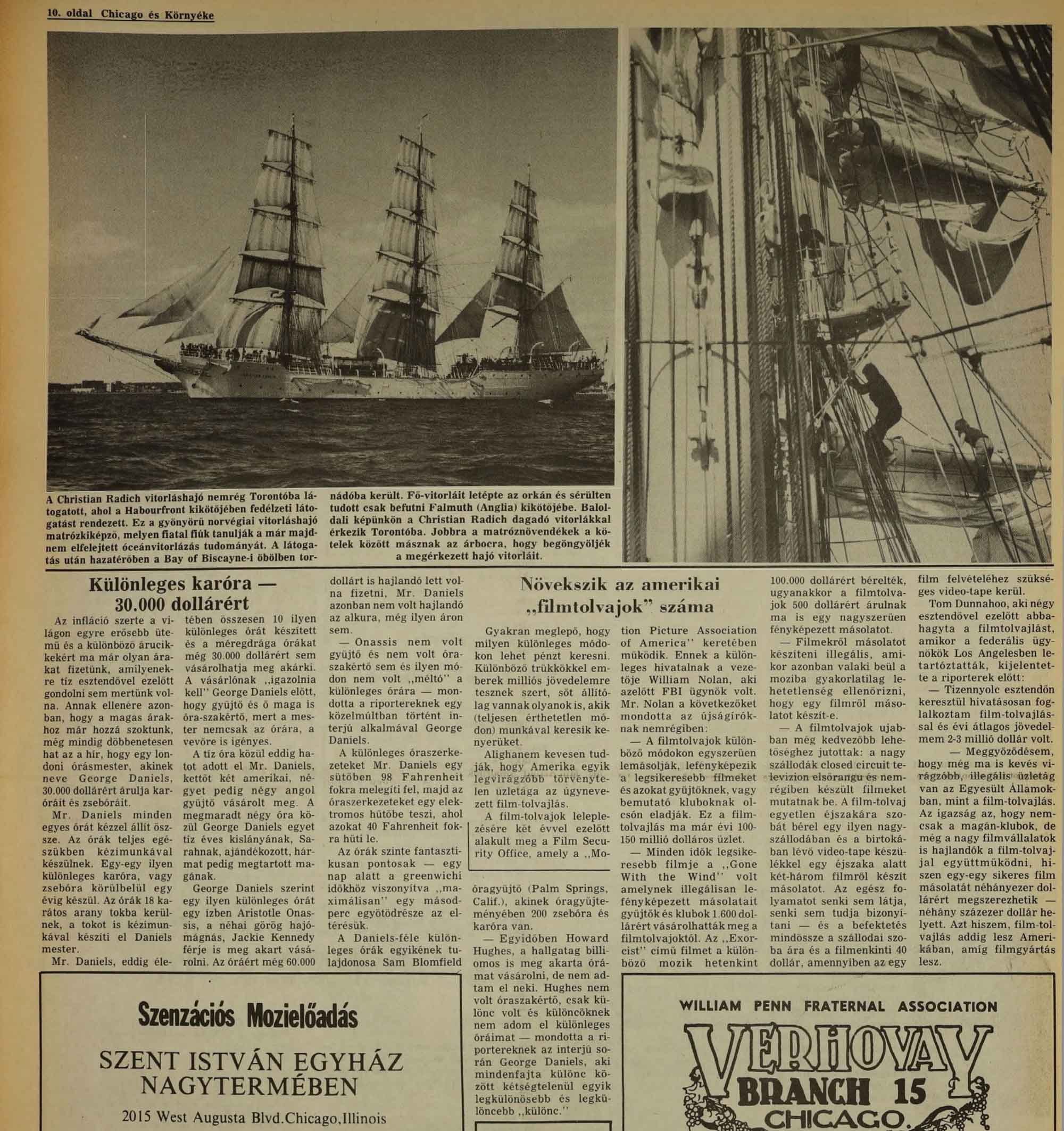

George Daniels Denies Selling His Watch To Billionaire Howard Hughes & Aristotle Onassis — Chicago és Környéke, 1976. October 16 / Issue 42.

Context: Neither Aristotle Onassis nor George Daniels had been at all famous in the eyes of the greater Hungarian public of the 1970s, I can assure you of that. And yet, this news somehow made it into an article in the Chicago And Its Surroundings paper. Maybe the Chicagoan Hungarians knew one or the other… Anyhow, this contemporary reportage gives us a fascinating look into the very code of conduct that had its part in making George Daniels such a renowned figure in modern watchmaking. Meanwhile, Aristotle Socrates Onassis was a Greek shipping magnate who amassed the world’s largest privately owned shipping fleet and was one of the world’s richest and most famous men.

This is the page on which the story shows up, we used portraits of George Daniels CBE from other newspapers of the time.

“Although we have gotten used to prices inflating at an ever-growing pace, it will shock you to hear that a Londoner watchmaker, George Daniels, is selling his watches for $30,000 a piece. Mr. Daniels makes each watch entirely by hand, producing one piece a year in 18k gold cases that he himself also manufactures. To date, Mr. Daniels has produced 10 such watches in his life, and even at 30’000 dollars, not everyone is allowed to purchase one of his creations.”

Raised in an extremely poor family, George Daniels’ outstanding talent has nevertheless found the means of becoming truly successful. Daniels became a renowned collector of Bentley motorcars, among other things.

“The customer has to justify himself as a true collector and horological savant to George Daniels, as the master is demanding not only of his own work, but his clientele as well. Of the 10 watches, Mr. Daniels has thus far sold 6 — two to American and four to English collectors. Of the four remaining pieces he gifted one to his 10-year-old daughter, Sarah, and three he has kept for himself.”

“According to George Daniels, Aristotle Onassis, the Greek ex-shipping-magnate and husband of Jackie Kennedy, wanted to buy one of his watches for a sum of $60,000, but Mr. Daniels denied him — Onassis was not a collector and was not a savant of watchmaking, and so he was not »worthy« of that special watch — George Daniels told reporters in a recent interview. An owner of a Daniels watch is Sam Blomfield watch collector (Palm Springs, Calif.), whose collection comprises 200 pocket watches and wristwatches.”

To learn more about George Daniels, watch this incredible interview here.

“For a time, Howard Hughes, the quiet billionaire, also wanted to purchase one of my watches, but I refused selling to him. Hughes was not a watch expert, just an eccentric, and to eccentrics I do not sell my watches,” George Daniels, who is the most eccentric among all eccentrics out there, told reporters. ”

Editor’s note: I’m not sure if “eccentric” was the word he used, but the phrase “különc” in Hungarian lines up rather well with that. That said, Mr. Daniels may have used another choice of words, so do not consider this a direct quote. That said, I found this a fantastic contemporary report on where Daniels had been in his career in 1976. And finding information like this may also be worth superimposing with information shared by auctioneers today.

Watchmaking In Budapest Gets A Charming Restart After World War II — Népszava, 1946. October 24 / Issue 241.

Context: These first few paragraphs from a 1946 newspaper really touched my heart. To this day, countless buildings in central Budapest bear on their facades the scars from bombs, explosives, and bullets fired in World War II and then during the bloody anti-Soviet “Hungarian Revolution” of 1956. Read about how “the remaining 8 workers” started rebuilding a watch and clock factory and faced the stark realities of post-war times.

“In a tranquil street of the VIII district is the rebuilt Clock Factory. In the Maytime of 1945, the eight remaining workers of the factory have seen to the tidying up of the factory. A lot needed doing. Evidences of bombardments and ruins were to be removed, truncated machines had to be made functional and the production of the Clock Factory was to be restarted.”

“Comrade Leveleki Gyula, the director of the Clock Factory, escorts us through the workshops. Wristwatches and pocket watches we cannot yet consider for production. We’d need foreign-sourced components to restart compact-watch production. We don’t yet have the required commercial connections to allow us to source the necessary parts, and we couldn’t afford them, anyhow. And so, for the time, they are making wall clocks and table clocks with precise, reliable 8-day movements, plus cab car clocks and chess game timers, with substantial foreign interest for the latter. They are also producing telephone automat parts required for war reparations.”

“A half-demolished building in Belváros [Downtown] houses the Clock Factory’s shop. The shopkeepers say the eight-day power reserve clock is proving to be very popular not only for its reliable movement, but also because it decorates the room. Meanwhile, lots of rusty watches and clocks are brought in, now recovered from their places of concealment. It is here that they are cleaned and fixed. Now better than new.”

Editor’s note: This isn’t quite the forum for a discussion on the horrors of World War II, or any war, for that matter. But this timid, yet diligent restart to making clocks marked a new dawn where such devices would be heavily relied upon in all walks of life in a heavy-hearted, restarting civilization.

A 1930s Scam? “Buy Our Discounted Watches & We’ll Promise To Ship” — Nemzeti Sport, 1930. May 11. / Issue 90. and Tutti di Sport, 1929. December 08.

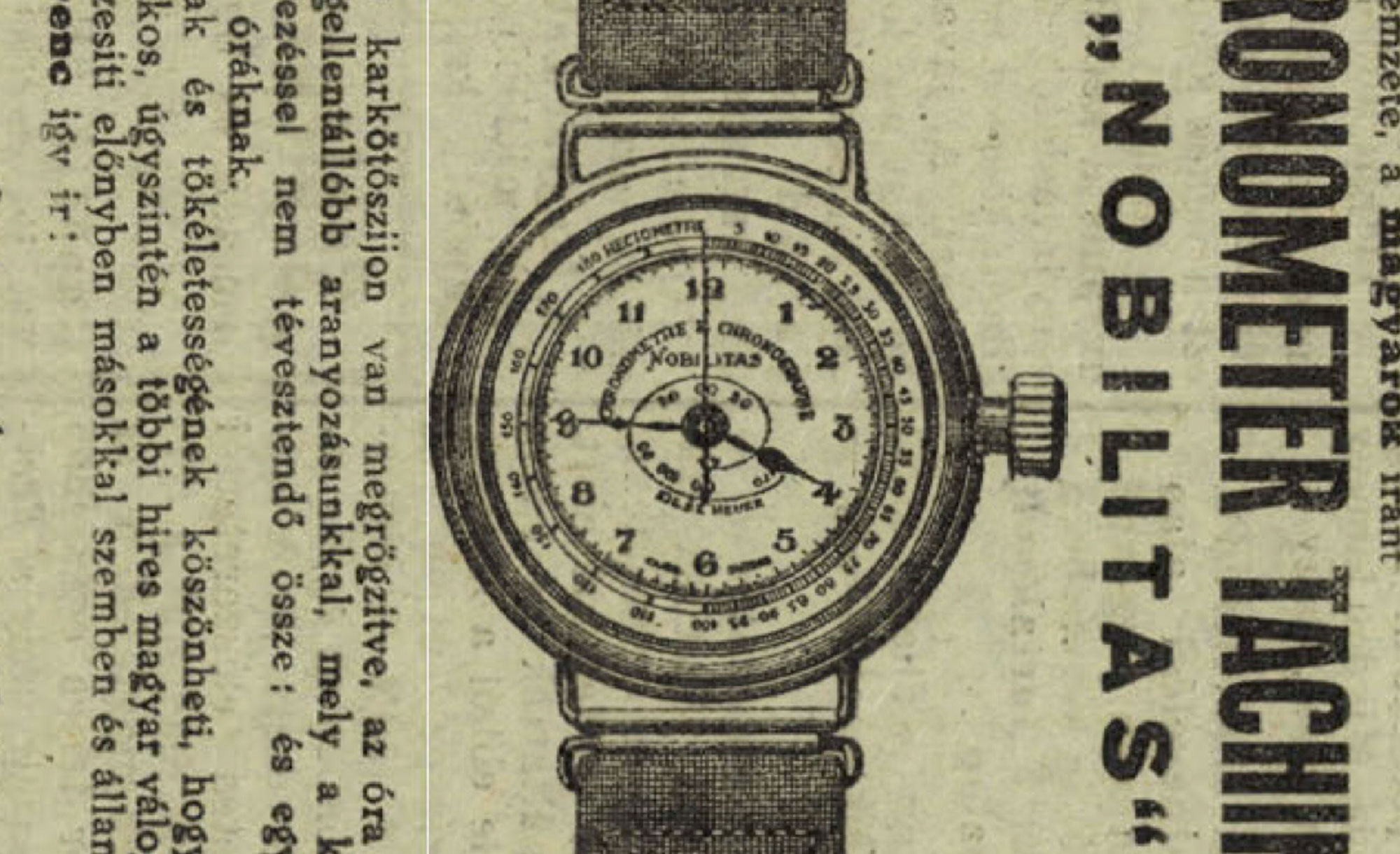

Context: Oh, how times were simpler back then. Whereas the Internet is not free from scams involving watches, I found something that I reckon to be the granddad of watch scams. This fascinating ad in a Hungarian sports magazine was posted by a watchmaker called “Fabbrica Svizzera di Cronometri e Orologi »Nobilitas.«” A quick Google search brought me zero hits, except for the exact same ad, but in Italian, posted six months before that. Here’s the bait:

“Recent American tariffs have prevented us in delivering a large Chronometer Tachimeter (sic!) order to our New Yorker representative. Our company is renowned globally for its seriousness and its outstanding products, and so we are proud that the greatest sportspeople, champions, and masses of the working classes prefer our wares. We are forced to not let this great asset fallow, and so we decided to offer you, our Hungarian friends, this Chronometer Tachimeter called Nobilitas, and we rejoice in saying that you are the first to be given this offer, as we have such strong fellow feelings and admiration for the greatest sporting nation of Europe, Hungarians.”

Editor’s note: Now, the Italian story reads exactly the same, except that in that version, surprisingly, they are the greatest sporting nation of Europe, i.e. “l’Italia, il paese piú sportivo d’Europa.” This section is followed by a short description of the “heavily gold-plated bracelet watch” and a (probably paid or faked) hand-written letter from a sportsman in Hungarian… And also in Italian.

The watch is marketed at a fraction of the price of its alleged competition, coming in at 15 Pengő in comparison to its 250-300 pengő priced chronometers. In Italy, the watch was marketed for 50 Lira and compared to others at 500-600 Lira — quite a bit of a difference, but hey. In closing the listing says: “Fabbrica Svizzera di Cronometri e Orologi »Nobilitas« LOCARNO (Switzerland)” and that “This listing will not be repeated. We ensure all our customers that the chronometers will sent on the very day that we receive your money.” Payments were possible over international postage payments, in checks, or mailed in cash.

Who knows, maybe the Chronometer Tachimeter “Nobilitas” was in fact the best watch deal in 1930… But from the looks of things, I seriously doubt that everyone who paid for one ended up a happy camper.